I love

the work of Leonora Carrington. It is always strange, often unsettling

and unfailingly magicaI, in terms of fame and renown, she’s

not as well known as some of her male contemporaries, including her

sometime partner Max Ernst, or Salvador Dali,

but I believe she should be.

Born into an upper class, reactionary Lancashire family in 1917, she soon discovered the restrictive and mentally stifling penalties that go with the privileges of bourgeois existence. But conformity was not an option. When she was eight her Catholic parents sent her to the Holy Sepulchre convent in Chelmsford, where she refused to do any schoolwork.. Even as a young girl, Carrington was a non-conformist.She was an individual, unwilling to conform to authoritative, unreasonable rules. Her free-spirit and candid quips resulted in expulsions from at least two schools “anti-social tendencies and certain supernatural proclivities”. In Florence and Paris she revelled in the arts, but dodged her workload and school regime through running away. In the end, Carrington’s parents capitulated to their wilful debutante daughter when, in her teens, she announced her intention to study at Chelsea School of Art, and become a painter.Her life was to become an amazing journey of change and discovery.

Carrington,

understandably, was distraught. She stopped eating, and was in

dangerously poor health when she was rescued by some friends, fleeing

the Nazis, who drove her to Madrid. She wrote later: “I’d suffered

so much when Max was taken away to the camp, I entered a catatonic

state, and I was no longer suffering in an ordinary human dimension.”

On the journey to Spain she saw bodies hanging from trucks and corpses on the roads – at least she thought she did, though her traumatised mind wondered if they might actually be delusions. The Spanish authorities certainly thought so when she reported them, and threw her into an asylum in Santander. According to her 1944 memoir, Down Below, she suffered there, subjected to barbiturate and Cardiazol treatment, until her family in England got sufficiently worried about her to send a nanny to rescue her and take her instead to a hospital in South Africa. In the finest traditions of Surrealist weirdness, Carrington escaped from her minders while they were waiting to board the boat, jumped into a cab and headed straight for the Mexican embassy, immediately entering into a marriage of convenience with a diplomat friend she’d known in Paris. Then they went back to wait for a boat to the USA, joined by a liberated Ernst, his new partner, his ex-wife, and his new partner’s ex-husband. Carrington and Ernst didn’t get back together – he married again, and after a few months Carrington dissolved her own marriage and moved, permanently this time, to Mexico City.

It’s an extraordinary tale of surrealism, love and madness and more, some have claimed that Carrington’s asylum memoir was

more fiction than fact. (Interestingly, Amazon classes the book as

fiction.) But Anne Hoff of the University of Alabama wrote a paper on Down Below in

in 2009, concluding that Carrington’s barbaric experience could well

have been entirely factual. Clinical descriptions of other people’s

treatment with Cardiazol,

a powerful convulsive drug that was a forerunner of ECT, suggest her

recollections of seizures, hyper-sexualised thoughts post-treatment and

being left to lie in her own faeces (incontinence was a common

side-effect) are depressingly accurate. She was also given Luminol, a

powerful anti-convulsive. I can imagine it would have been an horrific ordeal that would have bound to leave a mark.In

her paintings and writings, she generates a heady fantasy world. It draws on

elements of folklore and fairytales, Celtic and other mythologies, a lot of this gets mixed up in her work plus elements from occult mystical traditions including alchemy. There’s a lot going on, I like them a lot, deep

dreamlike spaces of infinite possibility with a magical poetical quality. Like a magical alchemist she had the ability to smuggle cryptic messages or absurd spells into her art enabling her to transform the viewers eye. Often there are Gothic

undertones, maybe recalling the Lancashire mansion where she grew up in

and longed to escape, she was a rebel who was twice expelled from school, and was instinctively

opposed to her parents’ social aspirations.

Born into an upper class, reactionary Lancashire family in 1917, she soon discovered the restrictive and mentally stifling penalties that go with the privileges of bourgeois existence. But conformity was not an option. When she was eight her Catholic parents sent her to the Holy Sepulchre convent in Chelmsford, where she refused to do any schoolwork.. Even as a young girl, Carrington was a non-conformist.She was an individual, unwilling to conform to authoritative, unreasonable rules. Her free-spirit and candid quips resulted in expulsions from at least two schools “anti-social tendencies and certain supernatural proclivities”. In Florence and Paris she revelled in the arts, but dodged her workload and school regime through running away. In the end, Carrington’s parents capitulated to their wilful debutante daughter when, in her teens, she announced her intention to study at Chelsea School of Art, and become a painter.Her life was to become an amazing journey of change and discovery.

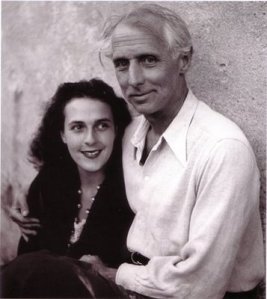

Having seen

the work of Max Ernst at a major surrealist exhibition in London, she

met him at a dinner party. He was 46 and married for the second time

but, almost immediately, they were captivated by one another and ran off together, to Cornwall and then to

Paris, where he separated from his wife, and Carrington found herself at

the heart of several charmed artistic circles variously including

Picasso, Dalí, André Breton, Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp

Joan Miró and others. Although she never considered herself a

card-carrying surrealist, she embraced the spirit of the movement with

theatrical zeal; for example, she reputedly turned up for a party

wrapped in a sheet, which she strategically discarded to reveal that she

was naked beneath it. She and Ernst were

reportedly known to clip the hair of their house guests as they slept,

then serve it to them mixed in their breakfast omelettes. Surrealism has/had a very uneven relationship with women, and this

has been discussed by many scholars throughout the years.'' Andre

Breton and many others involved in the movement regarded women to be

useful as muses but not seen as artists in their own right. Leonora

Carrington was embraced as a femme-enfant by the Surrealists because of

her rebelliousness against her upper-class upbringing. However,

Carrington did not just rebel against her family, she found ways in

which she could rebel against the Surrealists and their limited

perspective of women..Surrealism gave her a visual and

literary vocabulary to express herself whilst not avoiding

limitation.

Then

war broke out, the Germans invaded, and in time Ernst was interned by

the Vichy administration.for simply being German and then by invading

Nazis because his work was considered decadent and was locked up in an

internment camp.. It was the beginning of a profoundly

disturbing period for Carrington. She may already have suffered a

nervous

breakdown, hitched a lift with friends to Spain.

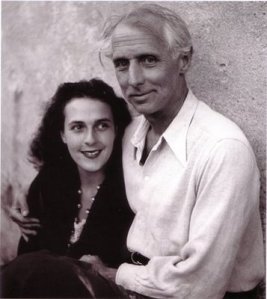

Portrait of Max Ernst

On the journey to Spain she saw bodies hanging from trucks and corpses on the roads – at least she thought she did, though her traumatised mind wondered if they might actually be delusions. The Spanish authorities certainly thought so when she reported them, and threw her into an asylum in Santander. According to her 1944 memoir, Down Below, she suffered there, subjected to barbiturate and Cardiazol treatment, until her family in England got sufficiently worried about her to send a nanny to rescue her and take her instead to a hospital in South Africa. In the finest traditions of Surrealist weirdness, Carrington escaped from her minders while they were waiting to board the boat, jumped into a cab and headed straight for the Mexican embassy, immediately entering into a marriage of convenience with a diplomat friend she’d known in Paris. Then they went back to wait for a boat to the USA, joined by a liberated Ernst, his new partner, his ex-wife, and his new partner’s ex-husband. Carrington and Ernst didn’t get back together – he married again, and after a few months Carrington dissolved her own marriage and moved, permanently this time, to Mexico City.

Leoonora Carrington and Max Ernst

The fantasy in her work is sometimes disturbing with a violent, edge. It draws from her own disturbed personal experience and emotional life, her own and of

course many others, in a way that links her to such artists as Louise Bouergois , Paula Rego and Frida Kahlo. In line

with the male surrealists’ view of the role of women, she was often

assigned the subservient role of muse to Ernst, implicitly diminishing

her, even though she remarked that she was far too busy getting on with

things to be a muse.

A big influence on her was Robert Graves’s The White Goddess . Drawing on a range of European mythology,

especially the Welsh and Irish traditions, Graves controversially

proposed the presence of a consistent, if variously named and depicted,

goddess. In doing so he was revealing an alternative, potentially

feminist mythological and religious predecessor to familiar, patriarchal

models.The White Goddess appears again and again in her work such as Then we saw the daughter of the minotaur (1953) is not to he a relic from a lost religion but to a living (dancing) entity in the present. Add to this influence Carrington’s memories of stories told to

her by her mother and her cherished Irish nanny, Mary Kavanagh and you can begin to see what she’s getting at in her pictures, even if nothing quite prepares us for their edgy strangeness.

Then we saw the daughter of the Minotaur

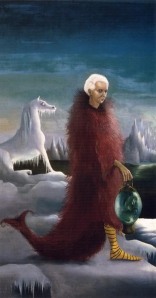

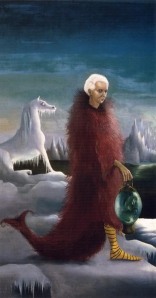

In her painting, 'The Giantess', the guardian of the egg, 1947, and painted for her patron, Edward James, possibly Carrington's most famous work, The Giantess, is dwarfing land and sea, ''drawing out the psychic prowess of the Goddess, her regenerative life-giving properties, and her fertile creative powers. This Goddess-centred spirituality, benevolent and nurturing, emanates from the giantess: the birds flock from her robes, and between her palms she clasps a mysterious black egg, perhaps the source of new life.''

Carrington said, ''The egg is the macrocosm and the microcosm, the dividing line between the Big and the Small which makes it impossible to see the whole. To possess a telescope without its other essential half – the microscope – seems to me a symbol of the darkest incomprehension. The task of the right eye is to peer into the telescope while the left eye peers into the microscope.''

The Giantess , 1950

Then we saw the daughter of the Minotaur

In her painting, 'The Giantess', the guardian of the egg, 1947, and painted for her patron, Edward James, possibly Carrington's most famous work, The Giantess, is dwarfing land and sea, ''drawing out the psychic prowess of the Goddess, her regenerative life-giving properties, and her fertile creative powers. This Goddess-centred spirituality, benevolent and nurturing, emanates from the giantess: the birds flock from her robes, and between her palms she clasps a mysterious black egg, perhaps the source of new life.''

Carrington said, ''The egg is the macrocosm and the microcosm, the dividing line between the Big and the Small which makes it impossible to see the whole. To possess a telescope without its other essential half – the microscope – seems to me a symbol of the darkest incomprehension. The task of the right eye is to peer into the telescope while the left eye peers into the microscope.''

The Giantess , 1950

Alongside her painting and sculpture she was also a prolific writer prolific writer with many articles, novels, essays, and poems to her name. Apart from the autobiographical Down Below, her most celebrated piece was a dream fairy-tale of 1974, The Hearing Trumpet. Her books are as utterly imaginative as her visual art.In The Hearing Trumpet ( a favourite book of mine), Carrington appears under the alias Marian Leatherby, who is 92 and has a beard. She has no teeth left and has become vegetarian an elderly woman getting irritated by her patronising family, who think her senile. But the care home that she is carted off to is unlike any establishment of its kind. Marian discovers evidence of mysterious gatherings, disappearances, and hints of the supernatural. Ultimately, all this leads to a total reordering of the terrestrial order: a world "transformed by the snow and ice.” Marian anticipates the day when “the planet is peopled with cats, werewolves, bees, and goats. We all fervently hope that this will be an improvement on humanity. "I'll leave you to discover the pure magical joy of her writing for yourself, I strongly recommend her..Her other notable books were The House of Fear (1938), The Oval Lady (1939), The Stone Door (1976), Pigeon Flies (1986) and The Seventh Horse (1988). She also wrote the plays The Debutante (1937), A Flannel Night-Shirt (1951), Penelope (1957) and The Invention of the Mass (1969).

After her move to Mexico in 1943 a new chapter began. Free of her family and her besieged relationship with Ernst (he married Peggy Guggenheim to escape Europe), she immersed herself in the art world of Mexico City. Steeped in Surrealist ideas and mysticism, she joined a close group of artists and enjoyed much creative experimentation.. Here in Mexico there was Aztec and Mayan culture, Catholicism and Spanish colonialism all mixed together in a vast, steaming cauldron of exotic images. Snakes, saints, candles, life and death, dark and light. Vast brooding volcanoes, huge pyramids, mythical dragons. The young artist from England had found her ‘milieu’. In her novels and her art, Leonora combined her favoured symbols of folklore with Mexican motifs. El Mundo mágico de los Mayas, 1963-4, was a commission for a new museum, in an area dedicated to the state of Chiapas. She visited the region, attended healing ceremonies in order to get to know the people. Carrington was accepted as someone who spoke for Mexican history as well as engaged with its culture, history and art. She attempted to study the preconquest outlook of the Chiapas Indians, and in her finished painting shows the way cultures were mixed in the area. The painting is a fairytale of old and new, historical and imagined. Figures walk between Catholic processions and indigenous healings. Mystical animals swirl around a landscape that seems a living creature itself, while her favourite motif, the Irish white horse, sits amidst a carnival of human activity.

From El Mundo de Magica Mundos

Who art , though white face

The student demonstrations of 1968 revealed a further facet of Carrington's personality, her political militancy.In 1969 she continued to make her views heard in a series of public appearances. In particular she championed the newly established women's movement: in the early 1970s she was responsible for co-founding the Women's Liberation Movement in Mexico; she frequently spoke about women's "legendary powers" and the need for women to take back "the rights that belonged to them". Take this wonderful quote from her " it is impossible to understand how millions and millions of people all obey a sickly collection of gentlemen that call themmselves ' Government'! The word I expect frightens people. It is a form of planetary hypnosis and very unhealthy" from 'The Hearing Trumpet'

The rest of Leonora’s life remained blissfully quiet and stable. Having only married for convenience, Leonora and Leduc split. She met Hungarian photographer, Chiki Weisz and had two boys, Gabriel and Pablo. She planted a tree in her front yard, taped pictures of Queen Elizabeth and Princess Diana on her kitchen cabinets, drank PG tea in the afternoons and tequila at night. She continued to paint and write, building a sizeable repertoire of fantastical surrealist works depicting mythical, made-up creatures representing themes of identity and transformation. She had once again constructed her own lovely little universe where she was bound by no one, free to be and create as she wished. So finally Leonora Carrington died on this day at the age of 94, after what was a remarkable life. Described as “the last great living surrealist” by the Mexican poet and activist, Homero Aridjis. Her legacy a mighty fine one that was later carried by other female artists, with their own sense of liberation, Frida Kahlo included, who fought for the rightful place of women in arts and in everyday life.

Leonora Carrington - self-portrait , 1937