Leonora Carrington who was born on the 6th of April 1917 spent her childhood on her family estate in Lancashire, England. There she was surrounded by animals, especially horses, and she grew up listening to her Irish nanny's fairytales and stories from Celtic folklore, sources of symbolism that would later inspire her artwork. Carrington was a rebellious and disobedient child, educated by a succession of governesses, tutors, and nuns, and she was expelled from two convent schools in acts of rebellion against the Catholic Church and her family whose excessive piety she loathed. Carrington also despised the capitalist ideals of her father Harold Carrington, a wealthy textile manufacturer in Lancashire, and broke free to artistic and personal freedom.

In The Tempation of St Anthony Carrington brings these two things together. When he was 20 years old St Anthony's father died leaving him a large sum of money. After subsequently reading Mathew's Gospel in which the reader is encouraged to sell ones's possessions in exchange for treasures in heaven, St Anthony disposed of his inheritance and embraced asetticism, becomming a hermit. In the desert he was subjected to temptation by demons in much the same way as Jesus had been. Having resisted these temptations , St Anthony went on to found a monastery based on his own ascetic life. Carrington's interpretation is iconclastic, defying the conventions of Renaissance paintings that depict St Anthony resplondent in a red cloak. Although St Anthony is given a physical presence in Carrington's painting he appears as an emaciated hermit, the resplondent red cloak given instead to his tormentor.

When Carrignton continued to rebel, she was sent to

study art briefly in Florence, Italy. Carrington was impressed by the

medieval and Baroque sculpture and architecture she viewed there, and

she was particularly inspired by Italian Renaissance painting. When she

returned to London, Carrington's parents permitted her to study art,

first at the Chelsea School of Art and then at the school founded by

French expatriate and Cubist painter Amédée Ozenfant.

Before Leonora Carrington became one of the most representative faces of the surrealist movement, she went mad. In the late 1930s, the English debutante was living with her lover Max Ernst (more than 20 years her senior) in a farmhouse in Provence, when Ernst was imprisoned on a visit to Paris and sent to a concentration camp. As the German army advanced, Carrington fled across the Pyrenees into Spain, where, after exhibiting increasingly deranged behavior, she was interned in an insane asylum in Santander. Down Below is Carrington’s brief yet harrowing account of her journey to the other side of consciousness.

It was André Breton who encouraged Carrington to write down her

experience. Liberation of the mind was the ultimate aim of surrealism,

and Carrington, already consecrated as a surrealist femme-enfant,

a conduit for her much older lover to the realms of youth and mystery,

had now traveled further than any of them and lived to tell the tale.

While she was predisposed to find artistic merit in her experience of

madness, Carrington’s reasons for telling her story seem more personal

and therapeutic: “How can I write this when I’m afraid to think about

it? I am in terrible anguish, yet I cannot continue living alone with

such a memory…I know that once I write it down, I shall be delivered.”Before Leonora Carrington became one of the most representative faces of the surrealist movement, she went mad. In the late 1930s, the English debutante was living with her lover Max Ernst (more than 20 years her senior) in a farmhouse in Provence, when Ernst was imprisoned on a visit to Paris and sent to a concentration camp. As the German army advanced, Carrington fled across the Pyrenees into Spain, where, after exhibiting increasingly deranged behavior, she was interned in an insane asylum in Santander. Down Below is Carrington’s brief yet harrowing account of her journey to the other side of consciousness.

Carrington would often look back on this period of mental trauma as a source of inspiration for her art. Just as in Carl Gustav Jung’s famous psychosis, Carrington emerged with a firmer stance on her individual purpose. Thus, on your journey you should embrace abnormalities and eccentricities; trusting that your mind will lead you to a greater path.

In 1941 Carrington married the Mexican poet and diplomat Renato Leduc, a friend of Pablo Picasso. In their short-lived partnership, Carrington and Leduc traveled to New York before eventually requesting an amiable divorce.

In 1943, after a short stay in New York, Carrington moved to Mexico,here she met the Jewish Hungarian photographer Emeric ("Chiki") Weisz, and the darkroom manager for Robert Capa during the Spanish Civil War. whom she married and with whom she had two sons, Pablo and Gabriel. Carrington devoted herself to her artwork in the 1940s and 1950s, developing an intensely personal Surrealist sensibility that combined autobiographical and occult symbolism. She grew close with several other Surrealists then working in Mexico, including Remedios Varo and Benjamin Péret.

A central theme for many of the women Surrealists was alchemy and their possession of its secret powers, which for them was linked to the mysterious cylcles of nature. Andre Breton had already put forward the proposal that women possessed these Hermetic powers and suggested that men could unlock these secrets by means of love. Some women Surrealists sought their own enpowerment of this resource for picture making believing that the origins of their own creativity were rested in Hermetic tradition.

Sharing her enthuiasm for alchemy with Vara (1908 -63), also a European exile, although their depictions are somewhat different they shared a common exploration in paint and poetry, of life's mysteries and its resolution using alchemy in her one-act play, Une Chernise de Nuit de Flanelle, written in 1945, Carrington developed characters that would later populate her paintings. One character, Prisne, populates the world of the living and dead, a theme that is used in Again the Gemini are in thee Orchard, the twins representing the same duality.The paintings allusion to fertility, through the allegory of the garden, suggests that this duality is part of the life cycle of humanity.

There are two constant motifs in Carringtons work after 1945, the partridge and other bird and the egg. the parttridge makes a number of appearances in Carrington's work, most famously in Portrait of the late Mrs Partridge from 1947 is seen walking with a partridge that is not to scale and appears incongrous. In one hand the woman carries an egg, while the other gently rsts on the back of the overgrown partridge.

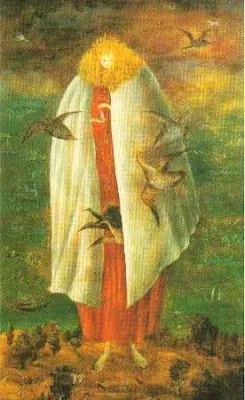

The incongruity of scale also appears in Baby Giant. This time the central figure is surrounded by normal scale birds, resembling geese, flying around her and from inside her cape. However, she is standing within two Liliputian worlds. The first is a hunting scene at the bottom of the picture, redolent of a Hieronymus Bosch painting, the other is a seascape in which appear Viking ships, whales and various sea creatures. The central figure has a mane of wheat that replaces her hair and is carrying an egg very carefully with both hands. These symbols of the generative and regenerative powers of nature, as exemplified by the egg, are key motifs in the work of many of the Surrealist women artists. For Carrington in particular, the egg also represented the alchemist's oven.

Women artists, however even those within the Surrealist coterie, still found themselves outside the circle that formulated Surrealist theories, though they nevertheless contribued significantly to its language. The erotic biolence in the art of thir male conterparts was replaced by an art of magical fantasy that still managed to shift the depiction of the female within a male dominated movement. In place of depicting women as 'other' as her male counterparts had done, women artists like Carrington depicted women as self'anticipating the female artists of the 1970's by some 40 years or so.

In 1947 Carrington was invited to participate in an international exhibition of Surrealism at the Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York, where her work was immediately celebrated as visionary and uniquely feminine. Her work was also featured in group exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art and at Peggy Guggenheim's Art of this Century Gallery in New York.

Carrington's

early fascination with mysticism and fantastical creatures continued to

flourish in her paintings, prints, and works in other media, and she

found kindred artistic spirits through her collaboration with the

Surrealist theater group Poesia en Voz Alta and in her close friendship

with Varo. Her continuing artistic development was enhanced by her

exploration and study of thinkers like Carl Jung, the religious beliefs of Buddhism and the Kabbalah, and local Mexican folklore and mysticism.

It is worth noting that she was very aware of and supported

feminist issues. In particular she championed the newly established

women’s movement: In the early 1970s she was responsible for co-founding

the Women’s Liberation Movement in Mexico; she frequently spoke about

women’s “legendary powers” and the need for women to take back “the

rights that belonged to them” ”Surrealism has/had a very uneven

relationship with women, as has been discussed by many scholars

throughout the years.” Andre Breton and many others involved in the

movement regarded women to be useful as muses but not seen as artists in

their own right. As Angela Carter once said, voicing the concerns of

many women artists of her time, “The Surrealists were not good with

women. That is why, although I thought they were wonderful, I had to

give them up in the end.” Leonora Carrington was embraced as a

femme-enfant by the Surrealists because of her rebelliousness against

her upper-class upbringing. However, Carrington did not just rebel

against her family, she found ways in which she could rebel against the

Surrealists and their limited perspective of women.

The student protests of 1968 revealed a further facet of

Carrington’s beliefs, her political militancy. In support of the

left-wing activists and as a remonstration, she left Mexico for a while

and returned in 1969 continuing to make her views heard in a series of

public appearances.

Today Carrington's

style is ecognizable worldwide, a combination of anthropomorphic

whimsy and an undercurrent of shadowy darkness. Yet she often rejected

the label "Surrealist," insisting instead that she painted what she

observed in the magical space between the corporeal world and the

subconscious.

Chilean

filmmaker and actor Alejandro Jodorowsky, a later Surrealist, wrote of

Carrington as one of his "witch" muses, yet she once remarked: "I didn't

have time to be anybody's muse; I was too busy rebelling against my

parents and learning to be an artist."

Carrington

was a prolific writer as well as a painter, publishing many articles

and short stories during her decades in Mexico and the novel The Hearing Trumpet (1976). Inspired by the country's

rich pre-Hispanic civilizations and the mythologies and occult knowledge

of cultures from around the world. One of her best-known works is an

enormous mural titled "The Magical World of the Maya," commissioned in

the early 1960s for the National Museum of Anthropology.

She also collaborated with other members of the avant-garde and with intellectuals such as writer Octavio Paz (for whom she created costumes for a play) and filmmakerLuis Bunuel. In 1960 Carrington was honored with a major retrospective of her work held at the Museo Nacional de Arte Moderno in Mexico City.

She also collaborated with other members of the avant-garde and with intellectuals such as writer Octavio Paz (for whom she created costumes for a play) and filmmakerLuis Bunuel. In 1960 Carrington was honored with a major retrospective of her work held at the Museo Nacional de Arte Moderno in Mexico City.

After a battle with pneumonia, Carrington died in Mexico City on May 25,

2011, aged 94. Her work continues to be shown at exhibitions across the

world, from Mexico to New York to her native Britain. In 2013,

Carrington's work had a major retrospective at the Irish Museum of

Modern Art in Dublin, and in 2015, a Google Doodle commemorated what

would have been her 98th birthday. By the time of her death, Leonora

Carrington was one of the last-surviving Surrealist artists, and

undoubtedly one of the most unique. Carrington's life was a whirlwind tribute to creative struggle and artistic revolution, that still is of great interest to me.

For an earlier post of mine on her see here https://teifidancer-teifidancer.blogspot.com/2016/05/the-magical-world-of-surrealist-leonora.html

Leonora Carrington - Self Portrait (1937 -1938)

No comments:

Post a Comment