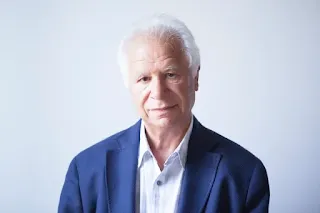

The celebrated Palestinian poet Mourid Barghouti, a

staunch supporter of the Palestinian cause, died on Sunday at the age

of 76.There has been no immediate announcement on the cause of his death. On his official Facebook page, his son, the well known poet Tamim Al Barghouti,

mourned his father.

Barghouti, was born on the 8th of July in 1944 in the mountainous village of Deir

Ghassanah, west of the River Jordan in Palestine. The cluster of villages was dominated by the Barghouti clan (the name

he delights in means flea) of politicians, poets and landowners. His

father worked the land, then joined the Jordanian army. Aged four when

the state of Israel was declared, Barghouti learned of the Palestinian

nakbah, or catastrophe,https://teifidancer-teifidancer.blogspot.com/2020/05/marking-72th-anniversary-of-nabka-day.html as non-Barghoutis with different dialects

appeared in his village. "I was told they were refugees. The story

unfolded of the destruction of villages, and the policy of ethnic

cleansing that drove them away." Hearing of a massacre at Deir Yassin https://teifidancer-teifidancer.blogspot.com/2019/04/remembering-deir-yassin.html in

April 1948 was "the nakbah for me as a child - stories of those killed

in cold blood that were disseminated all over Palestine. They were meant

to be, to encourage people to flee". The second of four brothers, he moved with his family to Ramallah,

aged seven. At school he admired the Iraqi modernist poet of the late

40s, Badr Shakir Al Sayyab, who broke the classical Arabic poem that had

survived for 15 centuries unchanged, during the surge of Arab

liberation movements against British and French occupation.

He moved to Cairo in 1963 to study English literature at Cairo

University and graduated in 1967, after which he didn’t go back to

Ramallah for 30 years. It was in Cairo that he met the love of his life, the Egyptian novelist Rawda Ashour who he married in 1970, staying together until her death in December 2014.In 1977 he was deported from Egypt after his opposition to the peace treaty between Egypt and Israel. The poet headed for Beirut, then left in 1981 for Budapest, where he

lived for 13 years. He returned to Egypt in 1994 to be reunited with his

wife and son.

He visited his birthplace in Palestine only after the peace agreement

signed between Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organisation in

1993.The event inspired his autobiographical novel Ra’aytu Ram Allah (I Saw Ramallah),

published by Bloomsbury in 2004 in a translation by Ahdaf Soueif, that

first won him an international audience.It was translated to English by

his late wife..The book won him the Naguib Prize in Literature in 2017. The late Edward Said saw

it as “one of the finest existential accounts of Palestinian

displacement”

Reflecting on crossing the bridge from Jordan to his West Bank

birthplace in 1996 after 30 years' exile - a visit under Israeli control

that he refused to call a return - he described a condition of

permanent uprootedness and the harrowing experience of a Palestinian who is denied the most elemental human rights in his occupied country, and in exile alike. It provided a view of Palestine that has been dispossessed and changed beyond recognition by usurpers. All writing,

for him, was a displacement, a striving to escape from the "dominant used

language" and the "chains of the tribe - its approval and taboos".

I Saw Ramallah, was followed by another book I Was Born There, I Was Born Here after Barghouti returned to the Occupied Territories. Barghouti weaved into his account of exile poignant evocations of Palestinian history and

life - the pleasure of coffee, arriving at just the right moment and as

an exile, the importance of being able to say, 'I was born here',

rather than 'I was born there'.

In all Barghouti published 12 poetry books in Arabic since the early 1970s,

as well as a 700-page Collected Works (1997). Midnight and Other Poems was his

first major collection in English translation.

He reflected on the cruelty of the Israeli occupation of Palestine, in particular the siege of Jenin in 2002 and wrote, “We

have been subjected to massacres at intervals throughout our lives.

Thus we find ourselves competing in a race between quickly realized mass

death and the ordinary life that we dream of every day. One day, I will

write a poem called “It´s Also Fine.”

It’s also fine to die in our beds

on a clean pillow

and among our friends.

It’s fine to die, once,

our hands crossed on our chests

empty and pale

with no scratches, no chains, no banners,

and no petitions.

It’s fine to have an undusty death,

no holes in our shirts,

and no evidence in our ribs.

It’s fine to die

with a white pillow, not the pavement, under our cheeks,

our hands resting in those of our loved ones,

surrounded by desperate doctors and nurses,

with nothing left but a graceful farewell,

paying no attention to history,

leaving this world as it is,

hoping that, someday, someone else

will change it.

His poems were translated into several languages, including English, French, Italian, German, Portuguese and Russian. He read his poetry and exhibited his books around he world, and lectured on Palestinian and Arab poetry at universiiies in Oxford, Manchester, Oslo, and Madrid, among others.

Although he was a member of the Palestinian Liberation Organisation, Barghouti did not identify with any political party. He spent years as the body's cultural attache in Budapest.Few poets managed to evoke the existential complexities of living in

exile and being stranded from a homeland as eloquently as Barghouti did. Barghouti reflected on his life under many regimes, seeing and witnessing

in them all the corruption of power and at the same time the

indomitable courage and resilience of the Palestinian people, their daily acts of resistance to occupation who in

just trying to live a normal life is an act of resistance. .

“The homeland does not leave the body until the last moment, the

moment of death.The fish,

Even in the fisherman's net,

Still carries

The smell of the sea."” Mourid Barghouti wrote in his award-winning

autobiographical novel I Saw Ramallah. the quote is now one of many by Barghouti being shared online as people pay tribute to the Midnight poet.

The Palestinian Minister of Culture, Atef Abu Seif, mourned the late

poet, saying that Palestinian and Arab culture had lost with his death

“a symbol of creativity and the Palestinian national cultural struggle.”

Abu Seif pointed out that Mourid Barghouti was “one of the creative

people who devoted their writings and creativity in defense of the

Palestinian cause, the story and struggle of our people, and Jerusalem,

the capital of the Palestinian existence.”

He may have envisioned his homeland leaving his body upon death, but his

contributions to Palestine and Arab literature will survive long after

he is gone. However, his death marks a great loss not just to Arab poetry but to world literature as a whole. Mourid Barghotti Rest in Power.

“People like poetry only in times of injustice—times of communal

silence—times when they are unable to speak or act. Poetry that whispers

and suggests—can only be felt by free men.”

"Silence said:/truth needs no eloquence./After the death of the

horseman,/ the homeward-bound horse/says everything/ without saying

anything." - Mourid Barghotti

No comments:

Post a Comment