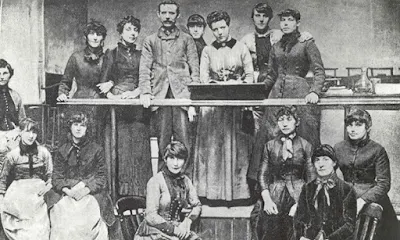

The Strike Committee of the Matchmakers Union

In the late 19th century Londons' East End was known for it's serious deprivation,,overpopulated by depressing living conditions, sweated industries, poverty and disease.

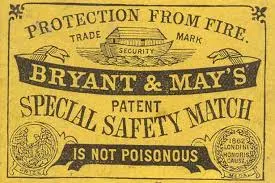

In 1850 the Quakers William Bryant and Frances May established Bryant & May to sell matches. At first they imported the matches from

Lundstrom’s in Sweden, but as demand outstripped supply, they decided to

produce their own, and set up a factory in Bow, in London,

producing hundreds of millions of matches each day. It was also the

largest employer of women in East London, with a staff of over 2,000

women and girls. Many of the poor, uneducated, and unskilled women they employed had come from Ireland following the potato famine. They lived in abject poverty, in filthy housing unfit for human

habitation and were often subject to prolonged hours of backbreaking

work making matches.

Despite their public reputation as philanthropists and Quakers, the factory owners subjected their wokers to awful conditions, their product was ironically called "safety matches" but they were far from safe for the women who made them. The matchmakers faced a life of hard toil for very little reward, earning a pittance while the company's shareholders recieved dividends of over 29%. Outraged by these exploitive conditions, crusading socialist journalist Annie Besant. having heard a complaint

against Bryant & May at a Fabian Society meeting –

resolved to investigate conditions in the factory for herself.When Besant went to speak to the factory girls in Bow,

she was appalled by what she found. Low pay and long hours were quite ubiquitous, but the Bryant & May

workers were treated without compassion and often endured physical abuse

and extortionate fines as punishment for shoddy work. Matchstick

manufacture came with particular health implications, and Bryant & May

did nothing to alleviate the effects of ‘phossy jaw’, a form of bone

cancer caused by the cheap white phosphorous that they used, causing yellowing of the skin and hair loss. The whole side of the face turned green and then black, discharging foul smelling pus and finally death. Additionally the condition caused jaw and tooth aches and swelling of the gums. The only treatment was the disfiguring cutting away of the affected areas. More expensive red phosphorous carried much lower risks to the women but the company refused to use it.

By 1888,

resentment had been building for some years,in 1882 Mr Bryant, wishing to curry favour

with the then present Prime Minister Mr Gladstone, arranged to have a

statue erected of him in front of St Mary's church. Nothing wrong with

this you might think until you learn that to pay for it he deducted a

certain amount each week from his workers wages. When it was unveiled

the matchgirls demonstrated by throwing stones, but this had little

effect on Bryant & May that was to come six years later

when the women down tools and walked out.

It was Annie Besant’s exposure of the terrible conditions at the

Bryant and May factory, after hearing a speech by Clemantine Black, at a Fabian society meeting on the subject of

Female Labour, in which she described the twelve-hour days and the inhumane, as well as dangerous working conditions at the Bryant & May factory that really brought matters to a head. It led to Besant’s

article in her socialist publication

The Link on 23rd June 1888 entitled

White Slavery in London which pulled no punches, depicting Bryant and

May as a tyrannical employer and calling for ‘

a special circle in the

Inferno for those who live on this misery, and suck wealth out of the

starvation of helpless girls’, and went on to describe how the match girls, some as young as

thirteen worked from 6am to 6pm with just two short breaks.

From their meagre wages her readers were told the women had to house,

feed and clothe themselves, the wages were further decreased if they

left a match on the bench and by the cost of paint, brushes and other

equipment they needed to do their work. Then apart from the likelihood

of developing 'phossy jaw' there were there dangers of losing a finger

or even a hand in unguarded machinery. Besant called the factory "

a prison-house" describing the match girls as "

white wage slaves" and "

oppressed"

Management were furious at the workforce

for the revelations, and reacted by attempting to force the workers to sign a statement that they were happy with their working conditions. When a group of women refused to sign, the organisers of this action were sacked and three women whom they suspected of leaking

information were fired. Outraged, 1,400 employees rose up in protest, including

girls as young as 12. on 5th July 1888, 1400 girls and women walked out of the Bryant and

May match factory in Bow, London and the next day some 200 of them

marched from Mile End to Bouverie Street, Annie Besant’s office, to ask

for her support. While Annie wasn’t an advocate of strike action, she

did agree to help them organise a Strike Committee.The firm first tried to force the women to condemn Besant. They refused,

smuggling out a warning note: ‘

Dear Lady, they have been trying to get

the poor girls to say it is all lies that has been printed and to sign a

paper…we will not sign…’

They stayed out for two weeks: as there was no

union to provide strike pay, the Match Girls went door to door raising

money in support of their cause, whilst Annie Besant and other members

of the Fabian Society started an emergency fund to distribute to

striking workers. A Strike Committee was formed and rallied support from the Press,

and some MPs. William Stad, the editor of the Pall Mall Gazette, Henry Hyde Champion of the Labour Elector and Catherine Booth of the Salvation Army, joined Besant in her campaign for better working conditions in the factory. However, other newspapers such as the Times, blamed Besant and other socialist agitators for the dispute, but in reality it was the brutal conditions that bred militancy within rather than it being imported in from outside.

Bryant & May tried to break the strike by threatening to move the

factory to Norway or to import blacklegs from Glasgow. The managing

director, Frederick Bryant, was already using his influence on the

press. His first statement was widely carried. 'His (sic) employees

were liars. Relations with them were very friendly until they had been

duped by socialist outsiders. He paid wages above the level of his

competitors. He did not use fines. Working conditions were

excellent...He would sue Mrs Besant for libel'.

'Mrs Besant' would not be intimidated. The next issue of The Link

invited Bryant to sue. Much better, she asserted, to sue her than to

sack defenceless poor women.She took a group of 50 workers to Parliament.

The women catalogued their grievances before a group of MPs, and,

afterwards, 'outside the House they linked arms and marched three

abreast along the Embankment...' Besant's propagandist style was bold and

effective and she had a fine eye for the importance of organisation.

She addressed the problem of finance. An appeal was launched in The

Link. Every contribution was listed from the pounds of middle class

sympathisers to the pennies of the workers. Large marches and rallies

were organised in Regents Park in the West End as well as Victoria Park

and Mile End Waste in the east.

The strike committee called for support

from the London Trades Council, the most prominent labour organisations of the day,who responded positively, donating £20

to the strike fund and offering to act as mediators between the

strikers and the employer. The London Trades

Council, along with the Strike Committee of eight Match girls, met with the

Bryant & May Directors to put their case. Such was the negative publicity, directed by middle class activist Annie Besant, it overwhelmed the owners of the factory, By 17th July, their demands

were met and terms agreed in principle, the company announced that it was willing to re-employ the dismissed women and bring an end to the fines system, the Strike Committee put the

proposals to the rest of the girls and they enthusiastically approved

and returned to work in triumph. The Quaker reputation as good employers was tarnished by this strike:

whatever the reasons, Bryant and May had not taken the care of their

employees that people expected of Quakers. Disappointingly, though, it wasn’t until 1906 – almost 20 years later – that white phosphorous was made illegal.Partly because of Annie's journalism and mainly because of the remarkable courage of the factory women , the Bryant & May dispute was the first strike by unorganised worker to have garnered widespread publicity, with public sympathy and support being enormous. One of the Matchgirls' most enduring successes was to secure Bryant & May's agreement for them to form a union. The inaugural meeting of the new Union of Women Match Makes took place at Stepney Meeting Hall on 27th July and 12 women were elected and it became the largest female union in the country.

Clementina Black from the Women's Trade Union

League gave advice on rules, subscriptions and elections. Annie Besant

was elected the first secretary. With money left over from the strike

fund, plus some money raised from a benefit at the Princess Theatre,

enough money was raised to enable the union to acquire permanent

premises.

By the end of the year, the union changed its

rules and name. It became the Matchmakers Union, open to men and women,

and the following year sent its first delegate to the Trade Union

Congress.

The Matchmakers Union ceased to exist in 1903, but this strike in 1888 was unprecedented and changed the character of organised labour, it was a landmark victory in working-class history. A history lesson that should be taught in our school

s As such, it was a vital moment for both female empowerment and the increasing momentum of the workers’ cause. The strike had a significance that is difficult to put into words. In its physical scale it was unremarkable for the period, but its significance for the future of the British trade union movement was colossal, since the strike redefined the very nature of trade unionism, and because of its success helped to inspire the formation of unions all over the country, and helped give birth to our modern-day general unions and laid down the foundations of the rights of women workers. A story that has inspired activists ever since, a symbol of what can be achieved when people bond together in solidarity, that has seen plays and musicals being written about the triumph of the Matchwomen, which saw Bryant & May dogged by the notorious association until it stopped trading in 1979.

The match girls’ success gave the working class a new awareness of their

power, and unions sprang up in industries where unskilled workers had

previously remained unorganized, as these new unions sprang up in the years that followed, new leaders of the working class emerged, people like Tom Mann, Will Thorne, John Burns and Ben Tillett and one year after the strike in 1889 it would see a sharp upturn in strikes, most notably the Great Dock Strike involving workers from across the Docklands area,confident that if the match girls could succeed, then so could they.

In 1892, philosopher and social

scientist Friedrich Engels highlighted this new mass movement as the most important sign of the times:

“

That immense haunt of human misery [the East End] is no longer the

stagnant pool it was six years ago. It has shaken off its torpid

despair, it has returned to life, and has become the home of what is

called the ‘new unionism’, that is to say, of the organisation of the

great mass of ‘unskilled’ workers. This organisation may to a great

extent adopt the forms of the old unions of ‘skilled’ workers, but it is

essentially different in character.

“The old unions preserve the tradition of the times when they were

founded, and look upon the wages system as a once for all established,

final fact, which they can at best modify in the interests of their

members. The new unions were founded at a time when the faith of the

eternity of the wages system was severely shaken; their founders and

promoters were socialists either consciously or by feeling; the masses,

whose adhesion gave them strength, were rough, neglected, looked down

upon by the working class aristocracy; but they had this immense

advantage, that [em]their minds were virgin soil[/em], entirely free

from the inherited ‘respectable’ bourgeois prejudices which hampered the

brains of the better situated ‘old’ unionists.

“And thus we see these new unions taking the lead of the

working-class movement generally and more and more taking in tow the

rich and proud ‘old’ unions.” (F Engels,

Preface to the English edition of The Condition of the Working Class in England, 1892)

The TUC (Trade Union Congress) commented that

the match girls strike is not just of historic interest.

" It is an absolutely critical example of how after decades of low

struggle and disappointment a militant movement can revive. Its genesis

could come from the most unpredictable and apparently unpromising

source."

The TUC went on to suggest that todays, call centre personnel, supermarket till staff and other poorly paid workers could use the matchmakers example as a springboard for improving their own working conditions. Women in their defiance, continue to challenge health inequality and

those who seek to oppress and exploit them not only nationally, but also

globally. Women in their droves are standing up for other women, and are no longer willing to accept poor health outcomes as an inevitability of their oppressed lives. Years after the matchmakers strike the flame against injustice is still kept very much alive, burning bright.

Further reading

A match to fire the Thames by Ann Stafford. Hodder and Stoughton, 1961.

Matchgirls strike 1888: the struggle against sweated labour in London's East End by Reg Beer. National Museum of Labour History, 1979.

“

It Just Went Like Tinder; the Mass Movement and New Unionism in Britain

1889: a Socialist History.” John Charlton, Redwords, 1999.

Striking a Light: The Bryant and May Matchwomen and their Place in History by

Louise Raw (2011)

Bloomsbury

British women trade unionists on strike at Bryant &May, 1888

https://microform.digital/boa/collections/53/british-women-trade-unionists-on-strike-at-bryant-may-1888/detailed-description