Richard Gary Brautigan American novelist, short story writer, poet, would have been ninety years old today had he lived.born on January 30 1935 in Tacoma, Washington where he was baptised as a catholic and where he would spend most of his childhood and teenage years.

Brautigan's mother said that Richard was a religious boy and read the Bible every night before bed. Brautigan attended church in Eugene—Lutheran, Baptist, and Catholic.

Richard Gary Brautigan grew up in the poverty of America’s Pacific Northwest during the Depression and World War II. His boyhood was without benefit of a father. An only child , Brautigan's parents, Bernard Frederick Brautigan and Lulu Mary Kehoe, married 18 July 1927, separated in April 1934, filed for divorce in 1938, which was officially declared in 1940. Brautigan claimed meeting his biological father only twice.

In Eugene, Brautigan attended middle and high school. Probably through English classes, he discovered the poetry of Emily Dickinson and William Carlos Williams. From Dickinson he drew the notion of the poet as eccentric outsider writing telegram-like messages from a parallel universe.

From Williams he learned to write in a contemporary vernacular about subjects that had immediate impact on readers. When he graduated from Eugene High School in 1953, Brautigan aspired to be a writer.

Brautigan had few friends. Mostly, he was alienated: the poor kid, the tall kid, the quiet kid, the writer. He hunted with a .22 caliber rifle, and fished, which seemed his second passion. Foremost was writing, which Brautigan used as both self-definition and an escape from what must have been a soul-crushing childhood of poverty, insecurity, and hunger.

In Brautigan’s juvenile writings, one can read his efforts to develop a unique authorial voice, come to grips with a dysfunctional family, and stake out his constant themes of alienation, loneliness, loss, and death.

Throughout childhood, Brautigan was known as Richard Porterfield. Just before his high school graduation, Mary Lu told Richard of his real father and he changed his surname to “Brautigan.”Given the adversity of his childhood, and looking ahead to his own life after high school, it is not unlikely that Brautigan wanted a new identity.

His first published poems appeared in local Oregon journals.Brautigan's first poem was this:

The Light

Into the sorrow of the night

Through the valley of dark despair

Across the black sea of iniquity

Where the wind is the cry of suffering

There came a glorious saving light

The light of eternal peace

Jesus Christ, the King of Kings.

Brautigan became an atheist, then began to play with the Christian tradition, and wrote, "I saw Jesus coming out of a pay toilet." But in 1955, barely twenty years old, he wrote to a friend, "I believe that God is going to help me become a literary sensation by summer. God has made me know something about myself. I know that I am a genius with creative power beyond description. And I am very humble about it."

He was arrested for disorderly behavior December 24th, 1955. Instead of prison he was sent to Oregon State Hospital where he was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia and subjected twelve times to ECT, electroconvulsive shock therapy. Eventually, he moved to San Francisco in 1956 where he would mostly remain the rest of his life.

It was here where he published his first volume of poetry and became involved with other writers of the emerging Beat movement, including the poets Robert Duncan, Michael McClure, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti.He was actually younger than the Beats and not thought by them to be serious enough; though he clearly loved hippie chicks, he stayed far away from drugs and the communal lifestyle of the Haight-Ashbury district he lived in during the Summer of Love,

His association with the socio-political group Diggers and Mad River exemplified a powerful personal connection to the youth culture of America, of which he seemed, at the time, the most representative, observing everything from the edges, and drinking with both Beat and more traditional poets at bars like No Name, Gino & Carlo’s, Vesuvio, and Enrico’s.

He published 23 short pieces in the radical San Francisco Rolling Stone, launched in the city in 1967, before the Sixties were out. Cult figure for sure, Brautigan happens to be one of my favourite writers, there are many, but it's Brautigan I return to more often than not when I want to smile, he also liked a drink or two or three,four and in his later work because of this it began to get dark.

The 1960s were his hey day and he was one of the most prominent to emerge from its counterculture. The Beatles loved him, not that that in itself means anything,were they not into most things. It comes as no surprise that John Lennon was a Brautigan fan.They both had a whimsical point of view that started in the square inch field and expanded into the cosmos.

Brautigan recorded a spoken-word album for The Beatles' record label, Zapple, between 1968 and 1969. However, the album was not released until 1970 on Harvest Records as Listening to Richard Brautigan. I've got a copu it's truly wonderful.

My first encounter with Brautigan’s writing was Beatle-related: he wrote a very haunting intro to the mass-market paperback The Beatles Lyrics Illustrated called “The Silence of Flooded Houses.”

Then I read his short story collection, The Revenge of the Lawn, and my lifelong love of his work began. I've since read and devoured nearly everything he wrote,

He showered readers of the 1960s and ’70s with inspiring spare, proletarian ideals in his novels. his works entwine pastoral American life and technological change with works that are often surreal while combining satire,parody and black humour.

In the following poem he foreshadowed the vise-like, smothering grip that technology has over us today.

All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace

I like to think

(and the sooner the better!)

of a cybernetic meadow

where mammals and computers

live together in mutually programming harmony

like pure water touching clear sky.

I like to think

(right now, please!)

of a cybernetic forest

filled with pines and electronics

where deer stroll peacefully

past computers

as if they were flowers

with spinning blossoms.

I like to think

(it has to be!)

of a cybernetic ecology

where we are free of our labors

and joined back to nature,

returned to our mammal

brothers and sisters,

and all watched over

by machines of loving grace.

All watched over by machines of loving Grace. Taken from the Adam Curtis series of the same name

There was something great in Brautigan. He claimed that drinking fueled it. But left alone, and without liquor, he was shy, a hard and precise worker who preferred his own company. A craftsman, he worried about commas, and was familiar with French and Japanese literature. He knew hundreds of important writers in Japan, America, and France, and could liven up parties with raucous wit.

Despite his prolificacy, critics reacted with diminished enthusiasm, put off by Brautigan's apparent preoccupation with sadness and death and his refusal to write further in his earlier, more humorous vein. Critics and readers trivialized his work, criticized its lack of political focus, and called Brautigan “naïve.”He often said he did not care about the critics, but losing his readers truly broke Brautigan's heart.

While his American audience turned its back, Japan embraced Brautigan and his writing. Brautigan traveled there often, staying at Tokyo's Keio Plaza Hotel. In Japan, he felt revered, the sensai. His experiences in Japan inspired a collection of seventy-seven poems entitled June 30th, June 30th (1978), and at least half of the short chapters in his novel, The Tokyo-Montana Express (1980).

This popularity abroad continues, with Brautigan’s writing translated into more than twenty languages. In America, his work is mostly out of print.

Underneath his humor was a swamp into which he was slowly sinking. He had never known his dad. His mother was a flibbertigibbet. She had had almost as many lovers as her son. She would store Richard with one ex-lover while going off with a new man, then retrieve her son after her passions cooled. Brautigan told his second wife, "I never thought I was loveable. I was abandoned by my mother."

Brautigan's second wife was a Japanese woman named Akiko. The sped-up romance that brought them together didn't allow either one to know what they were getting into. Brautigan suffered from enormous outbreaks of herpes that blotched his private areas and crawled up his belly and chest for months at a time. His new wife had to get used to this.

When Brautigan introduced Akiko to his friends in Livingston, Montana, she formally grasped each of twenty separate hands, and said, wearing a kimono, "How the fuck are you?" Brautigan tried not to laugh. He had taught her English. For her part, Akiko was a lot tougher than she looked. Friends of the family said she was smart. She left her first husband after getting together with Brautigan.

Brautigan's friend Don Carpenter warned Richard, "If she'll leave him, she'll leave you." She did, first sleeping with two of his friends when he left her in Montana for several months shortly after the wedding. Brautigan went to Tokyo and wrote 59 stories but returned to find a broken marriage.

By his late forties, he was a has-been, as the Flower Generation gave way to the Me Generation. Sales of his work had dwindled. He battled deep depression, punctuated by alcoholism, and he had guns.

Sadly Brautigan was found dead from a self-inflicted gun-shot wound in 1984, aged only 49, beside a bottle of alcohol and a .44 calibre gun. while living at 6 Terrace Avenue in Bolinas, California. He was discovered by a detective a month later with insects flying out of his splattered skull.

We all cast long shadows.Hauntingly his work still magically shines for me.Richard Brautigan was a goddamn force. A spiritual, intellectual, cultural and poetic force, and thankfully we still have the books he left us.

A Confederate General from Big Sur (1964) according to Newton Smith, the novel is the story of a character in Big Sur who imagines himself to be a general in the Confederate army, told by a narrator working on a textual analysis of the punctuation of Ecclesiastes. (Smith 123)

More specifically, Lee Mellon, the novel’s protagonist, believes he is the descendent of the only Confederate General to have come from Big Sur and is himself a seeker after truth in his own modern-day (1957) war against the status quo and the state of the Union. Brautigan’s friend an eccentric character called Price Dunn was the model for the novel’s Lee Mellon.

Brautigan’s 1967 novel Trout Fishing in America concerns a camping trip in Idaho’s Big Stanley Basin. The narrator clearly is Brautigan, who spent the summer of 1961 there with his first wife and daughter. It's subversive commentary on American life. Trout fishing is not only a pastime enjoyed by the novel’s narrator. It is also a character within the book, the embodiment of a primal national promise that mainstream American society and culture have rejected.

It features a scene in which a river is sold in a shop. It's funny and crazy, like the best of George Carlin, but is also poetic and can reach for a Proustian melancholy. It became an underground hit, credited with bridging the beat poets with the west-coast counter-culture.

In March 1994, a teenager named Peter Eastman Jr. from Carpinteria, California, legally changed his name to Trout Fishing in America, and now teaches English at Waseda University in Japan

The book launched a career that had, up to that point, been prolific but commercially unsuccessful. More novels followed, as well as collections of poetry and short stories.

His 1968 book In Watermelon Sugarwas Brautigan’s third published novel is the story of a successful commune called DEATH whose inhabitants survive in passive unity while a group of rebels live violently and end up dying in a mass suicide.It brilliantly blended themes of solitude and nature with our human intrusiveness. Always joyous reading. Always Brautigan.

The Abortion:An Historucal Romance from 1971 follows a young man, the narrator, who works and lives in the library, a Brautigan world of lonely pleasure, where he meets a woman. After impregnating the woman, the narrator supports her abortion. In the process he learns how to reenter human society. Inspiration for the Novel The inspiration for the library is factual.

First published in 1974, The Hawkline Monster was Richard Brautigan’s fifth published novel, and the first to parody a literary genre. Subtitled “A Gothic Western,” the novel was well received by a wider audience than Brautigan’s earlier work. As in earlier novels, Brautigan played with the idea that imagination has both good and bad ramifications, turning it into a monster with the power to turn objects and thoughts into whatever amused it.

In his 1976 novel' Sombrero Fallout the opening sentences of the book hooked me straight away: “A sombrero fell out of the sky and landed on the Main Street of town in front of the Mayor, his cousin and a person out of work. The day was scrubbed clean by the desert air. The sky was blue. It was the blue of human eyes, waiting for something to happen. There was no reason for a sombrero to fall out of the sky. No airplane or helicopter was passing overhead and it was not a religious holiday.”

That paragraph is the start of a story being written by an American humourist. However, the man is in the middle of an emotional trauma as his Japanese girlfriend has left him after two years together. Falling apart and unable to cope, he tears up his work and throws it into the waste paper basket. He will go on to try to make it through the night alone and abandoned; and in a parallel storyline Yukiko, his ex-lover, will sleep and dream, calm and happy with only her cat for company.

However, the story of the sombrero refuses to be abandoned, and while the writer and Yukiko are getting on with their lives, the tale of the town with the sombrero continues to develop in the waste bin. What seems a simple but inexplicable event – a sombrero which falls from the sky – causes all kinds of issues amd messes with his life. It’s a decent metaphor for our attempts to survive trauma.

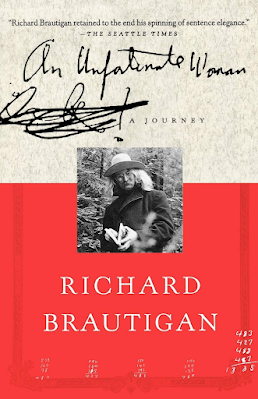

Those already familiar with his work may not know of the posthumous release of An Unfortunate Woman in 2000, a dark autobiographical novel written in the eighteen months before his death. It reveals a man no longer at ease with his own head – but the book reads beautifully all the same.

The 60 odd stories contained within Revenge to the Lawn I would say are his masterpieces, here's a few of them , hope you enjoy. Contained within one of my favourite short stories, it's also one of the smallest in my library. Prose poetry of the highest order.

Women When They Put Their Clothes on in the morning

It's really a very beautiful exchange of values when women put their clothes on in the mornig and she is brand-new and you've never seen her put on her clothes before.

You've been lovers and you've slept together and there's nothing more you can do about that, so iy's time for her to put her clothes on.

Maybe you've already had breakfast and she's slipped her sweater on to cook a nice bare-assed breakfast for you, padding in sweet flesh around the kitchen, and you both discussed in length the poetry of Rilke which she knew a great deal about, surprising you.

But now it's time for her to put her clothes on because you've both had so much coffee that you can't drink any more and it's time for her to go home and it's time for her to go to work and you want to stay there alone because you've got some things to do around the house and you're going outside together for a nice walk and it's time for you to go home and it's time for you to go to work and she's got some things that she wants to do around the house.

Or ...maybe it's even love.

But anyway:It's time for her to put her clothes on and it's so beautiful when she does it. Her body slowly dissapears and comes out quite nicely all in clothes. There's a virginial quality to it. She's got her clothes on, and the beginning is over.

Banners of My Own Choosing

Drunk laid and drunk unlaid and drunk laid again, it makes no difference. I return to this story as one who has been away but one who was always destined to return and perhaps that's for the best.

I found no statues nor bouquets of flowers, no beloved to say: 'Now we will fly banners from the castle, and they will be of your own choosing,' and to hold my hand again, to take my hand in yours.

None of that stuff for me.

My typewriter is fast enough as if it were a horse that's just escaped from the ether, plunging through silence, and the words gallop in order while outside the sun is shining.

Perhaps the words remember me.

It is the fourth day of Marcg 1964. The birds are singing on the back porch, a bunch of them in an aviary, and I try to sing with them: Drunk laid and drunk unlaid and drunk laid again, I'm back in town.

Lint

I'm haunted a little this evening by feelings that have no vocabulary and events that shold be explained in dimensions of lint rather than words.

I've been examining half-scraps of my childhood. They are pieces of distant life that have no form or meaning. They are things that just happened like lint.

The Scarlatti Tilt

' It's very hard to live in a studio apartment in San Jose with a man who's learning to play the violin.' That's what she told the police when she handed them the empty revolver.

Ernest Hemingway's Typist

It sounds like religios music. A friend of mine just came back from New York where he had Ernest Hemingway's typist do some typing for him.

He's a successful writer, so he went and got the very best which happens to be the woman who did Ernest Hemingways typing. It's enough to take your breath away, to marble your lungs with silence.

Ernest Heminway' typist!

She's every writer's dream come true with the appearance of her hands which are like a harsichord and the perfect intensity of her gaze and all to be followed by the profound sound of her typing.

He paid her fifteen dollars an hour. That's more than a plumber oran electrician gets.

$120 a day! for a typist!

He said that she does eveything for you. You must hand her the copy and like a miracle you have attractive, correct spelling and punctuation that is so beautiful that it brings tears to your eyes and paragraphs that look like Greek temples and she even finished sentences for you.

She's Ernest Heminway's

She's Ernest Hemingway's typist.

All above selections from

Revenge of the Lawn, Jonathan Cape 1972.

I would also strongly recommend a book of memoirs by his daughter Ianthe Brautigan's ' You can't catch death'. A fascinating glimpse into Richard Brautigans life and shedding light on some of his own personal ghosts.

Brautigan, the man and his work, has never been forgotten, far from it. Scholarly work exists that examines Brautigan’s career, and there are volumes of it at the click of a mouse. I would recommend all his books their wonderful, and can make you wonder, giggle and laugh out loud.

Though described as a ' outsider,' I don’t think this description entirely fits Brautigan; he was a purposeful artist who sought an audience, and thoigh there’s something about his off-kilter view of the world that subtly alters your own, they are so well crafted and draw you in, and whenever I return to his books, I'm never disappointed, and they still resonate to this day, and this is one of the reasons he still has a following after all these years.Long live Richard Brautigan.

' It's strange how the simple things in life go on while we become more difficult.' - Richard Brautigan

' I'll affect you slowly as if you were having a picnic in a dream. There will be no ants. It won’t rain'

-Richard Brautigan

' Reduce intellectual and emotional noise until you arrive at the silence of yourself and listen to it.'

- Richard Brautigan

Richard Brautigan

(a 5 minute presentation)

Richard Brautigan reads from Trout Fishing in Watermelon Sugar

.webp)