In 1877, a time of colonisation and conquest Lord Carnarvon, the Secretary of State for the colonies, wanted to extend British imperial influence in South Africa by creating a federation of British colonies and Boer republics. To ensure their security, they realised that they needed to pacify Zululand, which bordered their territory for the Zulus were renowned for their martial ability.

For some context settlers from Great Britain, the Netherlands, and elsewhere in Europe had been settling for centuries in fertile and geographically important southern Africa. After the carnage of the Thirty Years War in Europe (1618-1648), the land around Cape Town in southwest Africa was settled by the Boers, immigrants from the Netherlands, beginning in 1652. Under the auspices of the Dutch East India company, the settlers established a Boer colony in 1671. French Huguenots joined the colony in 1689. Over the decades, Boers traveled east to establish colonies across the southern tip of Africa. Holland fell to revolutionary France in 1795 and invaded its European neighbors. As part of the war with France, Britain attacked the Dutch Cape Colony 1795, 1803, and formally annexed it in 1814. As the United Kingdom kept annexing territories, tensions continued between the British, Boers, and black African neighbors for the next century.

To try and avoid conflict with the Zulu people, Carnarvon gave the King of the Zulus, Cetshwayo, the option to surrender and disband his armies to make way for British rule and federation. When confronted with this unfavourable deal, Cetshwayo understandably refused. Thus the Anglo-Zulu war began in January 1879, when the British General Lord Chelmsford invaded Zululand.

The Army entered Zulu territory in three sections: the right column entered near the mouth of the Tugela river to secure the abandoned Missionary Station at Eshowe; the left column made for the formerly Dutch town of Utrecht and the middle column, led by Lord Chelmsford himself, crossed the Buffalo river at the outpost of Rorke’s Drift and tried to find the Zulu army.

On 22 January 1879, Chelmsford established a temporary camp for his column near Isandlwana, but neglected to strengthen its defences, only encircling his wagons around it. After receiving intelligence reports that part of the Zulu army was nearby, he led part of his force out to find them.

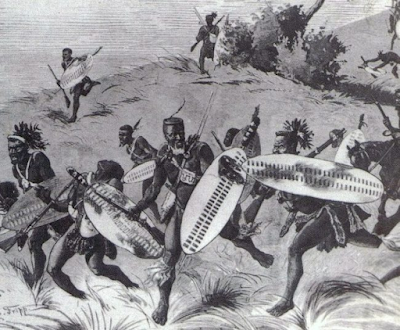

The lacklustre fortification proved a fatal error: a 20,000-strong Zulu warrior force the core of Cetshwayo’s army, launched a surprise attack on Chelmsford’s poorly-fortified camp. Fighting in an over-extended line which was too far from their ammunition, the British were swamped by the sheer volume of their enemies forces, and the difference in numbers proved to be fatal; the majority of their 1,700 troops were killed and both their supplies and ammunition were seized.

The Battle of Isandlwana https://teifidancer-teifidancer.blogspot.com/2022/01/remembering-battle-of-isandlwana-of-1879.html was a major defeat and nothing short of a disaster for the redcoats, one which forced Chelmsford to retreat. Toward the end of the battle, about 4,000 warriors who had not engaged in the fighting moved to cut off the British retreat.

Once complete, they crossed the river and turned their attention to Rorke’s Drift ,and its 140 soldiers, civilians, and patients.They were led by Dabulamanzi kapande, who was King Cetshwayo's half-brother and had commanded the Undi Corps at Isandlwana.

Sited near the banks of the Buffelsrivier, approximately 100 miles north of present-day Durban, Rorke’s Drift was originally a trading post established by James Rorke who had been the son of an Irish soldier who had fought in one of the many border wars against the local African tribes.

James Rorke on the other hand made a living by trading, hunting and the occasional gun-running with the natives until his suicide. His estate changed hands until it came to a Swedish missionary, who in turn leased the compound to the British colonial forces to use as a hospital and storage space.

The mission station was at this time occupied by Lt. Gonville Bromhead and his company, as well as 100 Natal Native Contingent troops, but Lieutenant John Chard from the Royal Engineers had been dispatched from the main army before the battle of Isandlwana began with orders to make defensive preparations at Rorke’s Drift, and as the senior officer, he took command.

In the film 'Zulu' it makes a point of suggesting that the 24th Regiment, and in particular 'B' Company, was mainly Welsh. In fact, the Welsh constituted only 11% of the 24th. Regt. at Rorke's Drift. Although the regiment was then based in Brecon in South Wales and called the 24th. Regiment of Foot (later to be the South Wales Borderers), it was formerly the Warwickshire Regiment.

Many of the defenders had never been to Brecon. Of the 24th Regt. at the defence, 49 were English, 18 Monmouthshire,16 Irish, 1 Scottish, 14 Welsh, 3 were born overseas. and 21 of unknown nationality.

As afternoon drew near, the wind carried the sounds of distant gunfire through the valleys to Rorke’s Drift. It was the distinct sound of the two 7-pounders that the British main body had carried with them. At first it caused little concern, for just a year earlier a small British force had triumphed over 6,000 Xhosa warriors, so this would surely go no differently.

As the cannon fire subsided, a lone rider came galloping towards them. The man was terrified and without his weapon, only repeating a single sentence over and over again.

More riders soon arrived, this time men of the Native Mounted Contingent. None spoke English but they had a note that read that the camp at Isandlwana was in danger of being overrun, becausethat Zulu forces were approaching..

Lieutenant Chard, had to decide whether to flee or fight. Given that the position had become more hospital than outpost, it was simply impossible to leave, as the injured occupants would travel too slowly and the fast Zulu army would inevitably kill them on the road. The only option was to stay and fight.

Rorke’s Drift was to be fortified at once. Under the guidance of Bromhead, Lieutenant John Chard and other officers, the men began barricading the missionary compound. Everything useful was dragged out of the storehouse, except for the kegs of rum and water. The reserve ammunition boxes were opened. They had 20,000 cartridges, enough to make a stand. They stockpiled food, mostly hardtack and bully beef, and stacked the heavy 200lb mealie bags and biscuit boxes into a defensive wall.

Most of the compound was shielded by a waist high stone fence, which they now reinforced. Both buildings were solid brick houses, though, with the larger storehouse being about 30m from the hospital, which was small, divided into 11 rooms and crammed with men who were now making shooting holes in the walls, while all windows and doors were barricaded. The men knew that their enemy would be merciless and spare no one, not even the wounded.

The last remaining biscuit boxes and mealie bags were used to create a barricade in front of the storehouse, a last keep in case of a breakthrough.As the evening drew nearer, the lookouts on the roof spotted the first Zulu warriors.There hadn’t been enough time to clear the fields around the station and there was plenty of cover for the enemy.

Any man who diminished morale was locked up.This was a crucial decision: it is hard to imagine the panic and sense of despair that the men must have felt knowing that thousands of Zulus, who had just defeated a well-equipped army of far greater numbers, were on their way and they, mostly classed as ‘walking wounded’, had to defeat them while being heavily outnumbered, vulnerable and with no hope of reinforcement from the main army.

At this point, the defenders numbered nearly 500 thanks to the assistance of native contingents of infantry and cavalry, The cavalry, numbering about 100 native troops who had retreated from the Battle of Isandlwana, took position on the far side of a large hill from where the Zulus were expected to approach.

Understandably, fear of the approaching army spread through the camp. As battle approached, the Swedish missionary assigned to the station, Otto Witt, fled with his companions. The cavalry troops briefly engaged the Zulus for the second time that day but also turned and ran.

The Zulus approaching Rorke’s Drift were of the 4,000 men strong Undi-Corps. During the battle at Isandlwana they had been part of the ‘Horns of the Buffalo’, the Zulu tactic to envelope their enemies. They had been tasked with widely outflanking the British but ultimately came too late to take part in the battle. The defeat of the British had been achieved without them and they had been denied glory.

The Zulu military organisation was divided by age and rank, and there was a deep rivalry between the regiments. Only those mature veteran regiments who had won glory in battle were awarded the rights to marry and to bear the sacred white shields into battle.

The Zulu warriors were not suicidal fanatics, but cunning, courageous and highly athletic light infantry men, in their physical prime, around 30 years old, hungering for pride and social status. They very much wanted to prove themselves. Led by Prince Dabulamanzi kampande, they had made their way to Rorke’s Drift well-versed in the art of war and under orders to show no mercy.

Skilled in using their traditional weapons One of their primary weapon was a light spear called an iklwa (or assegai), that could either be thrown or used in hand-to-hand combat. Many also used a club called an iwisa (or knockberrie). All warriors carried an oval shield made of oxhide.

A few Zulus equipped themselves with firearms (muskets), but most preferred their traditional equipment. Others were equipped with powerful Martini-Henry rifles, taken from the dead British soldiers at Isandlwana, and although they were untrained in handling those effectively, even an unskilled rifleman could find his target.

When they appeared on the scene, the Native Mounted Contingent had turned and fled, which left 154 men as the defenders of Rorke’s Drift, 20 of whom were ill.

At around 16:30, the battle began. The first Zulus attacked in a frenzy. Worked up by their witch doctors and narcotic stimulus, they charged towards the south wall of the mission, 600 warriors against only a few defenders.

The British soldiers fired into the advancing men. A trained British soldier was able to load and fire the Martini-Henry Rifle every 7-8 seconds, so people managed around 8-9 shots each in the time it took the Zulus to close in. They sprinted from cover to cover, disregarding the men that fell. At 200m, the rifle fire caused massive damage, as the Zulu shields offered no protection against the high calibre bullets, and just before they reached the barricade, the British officers ordered a salvo at point blank range.

The devastating effect of the fusillade broke much of the attack strength. Still, single men and small groups fought on, trying to scale the walls. Pumped up on adrenaline, they jabbed with their Assegai spears against the defenders, but once they tried to climb the barricades, they were easy targets for the longer British bayonets.

Once at the barricades, it was close quarter combat. The British officers dashed from point to point, revolvers in hand, inspiring the men to stand firm, shooting into the mass of attackers that pressed the defences. Where they could, the men worked together, one stabbing, the other reloading. The officers knew that the first battle they had to win was the psychological one; if the men faltered in fear, if they hesitated to kill or lost their heads in terror, all was lost.

The Zulus could not be allowed to enter the compound. The men did not hesitate. Desperation met aggression, and they knew that they would either fight or die At 17:00, the great mass of the Undi-Corps threw itself against the mission. The British held.

Soon a belt of corpses lay around the mission, another obstacle the attackers had to step over. The Chaplains and the wounded passed ammunition and water to the defenders. It was evening, but still, the sun was beating down and the constant fighting was exhausting and dehydrating. It was adrenaline and camaraderie that kept the men sharp. And still the Zulus came on.

By 17:30 the defenders were nearly overwhelmed. The lines were too thinly held and they now ran the risk of losing everything.The growing exhaustion and the casualties had made them retreat to the inner line and establish a centre of resistance around the storehouse, behind the walls of biscuit boxes and mealie bags.

By 18:00, the Zulu commanders on the other side were getting frustrated. This was supposed to be an easy battle, but the casualties were high and there had been no major break in yet. They had been fighting for 90 minutes, but the British line still held firm, though the hospital had been cut off.

In the close confines of the hospital, the defenders found it possible to stab their assailants one by one as they struggled to break through the narrow doorways. Private Hook killed five or six in succession in this way.

In the close fighting along the barricades, even the officers’ revolvers came into action to deadly effect. The revolver was so inaccurate at anything beyond point-blank range that it was normally considered only as a weapon of last resort, but in this sort of combat its rate of fire more than compensated for this disadvantage, so that even this weapon decisively outclassed the Zulu muskets.Several survivors, including Hitch, noted the good service performed by Lieutenant Bromhead’s revolver at a crucial point on the perimeter.

As the hospital was overrun, Private Williams was instructed to defend the window through which the Zulus were trying to enter while the others limped away. The intense firefight set the hospital ablaze and forced the patients to break their way through the wall which would allow them to escape behind the barricade.

After 15 minutes of hacking at the plaster wall, Private Hook made it through as the others continued to defend the hospital. 9 out of the 11 patients made it out. The escape from the hospital is famous for its demonstration of selfless bravery: the fit could have abandoned the invalid, but they left no man behind. Both Williams and Hook were awarded Victoria Crosses.

Soon it was surrounded, and the Zulus were throwing burning spears on the thatch roof. It caught fire and the men inside had no choice but to flee. Everything played out in a few minutes. Men jumped out of the windows, some making a dash across the compound. Others tried to carry the wounded and sick with them, while others fought the Zulus who were now breaking through the doors. They were cut down by the Zulus.

Darkness fell at 19:00. British ammunition was running low and rifles were running hot from constant use. Again, the Zulu tried to throw assegais wrapped with burning grass on the store-house roof but this time they were shot down in the attempt.

Slowly but surely, the Zulu spirit was wavering. Throughout the night the aggressive chanting was heard around the compound, but the major weakness of the Zulus, their lack of a supply system, was getting to them. They were hungry, thirsty and exhausted.

It was a sleepless night for the defenders, but as dawn broke, the Zulu were gone. The Zulu host may still appear, but they would no longer attack.After a while the British ventured out to the battlefield. They searched the remnants of the hospital for survivors, but it was a gruesome sight. The Zulu had hacked their comrades to pieces.

The official report said that 350 Zulus were counted dead, but according to diaries, it was many hundreds more. At 8 o’clock in the morning, a relief company finally appeared, and Rorke’s Drift was saved.

I first heard of battle of Rorke’s Drift incidentally when I was twelve, when I first saw the film Zulu, directed in 1964 by Cy Enfield, arguably, one of the greatest British war films of all time.The film stars Stanley Baker as Lieutenant John Chard and a young Michael Caine as Lieutenant Gonville Bromhead.and also featured the Welsh actor Ivor Emmanuel.

.It’s still one of my favorite movies, though am not into the glorification of war in any kind, but back in the day it made a colossal impact, and I even subsequently did a history project on it while a school, though nowadays acuially prefer the other film made about the conflict Zulu Dawn, which has more historical accuracy..

In the film Zulu we see the heroic Welsh garrison at Rorke's Drift match the awesome Zulu war-chants with a stirring rendition of Men of Harlech.but I'm sorry to say no one sang Men of Harlech, just a bit of artistic licemse. ;,

The Battle of Rorke’s Drift, a heroic defence of missionary station and hospital has since gone down in history as the ultimate example of the victorious underdog, where just over 150 British troops triumphed against an estimated 3,000 to 4,000 Zulu warriors. Rorke’s Drift was merely an outpost as opposed to a fortified position, and the defenders, and defences, were not fit to fight. Nonetheless, they prevailed against the battle-ready Zulu army.

A total of 11 Victoria Crosses would be awarded to the defenders for a victory against a force that had outnumbered them by far. The most ever awarded for a single action by one regiment.

The ultimate recipients were as follows:

Lieutenant John Rouse Merriott Chard

Lieutenant Gonville Bromhead

Corporal William Wilson Allen

Private Frederick Hitch

Private Alfred Henry Hook

Private Robert Jones

Private William Jones

Private John Williams Surgeon

Major James Henry Reynolds

Acting Assistant Commissary James Langley Dalton

Corporal Christian Ferdinand SchiessJones

Private John Williams Surgeon-

Major James Henry Reynolds Acting Assistant

Commissary James Langley Dalton

Corporal Christian Ferdinand Schiess

Cetshwayo had no bronze crosses or silver medals with which to decorate his heroes. But he did have a means of showing his special approbation. The wood of the Umzimbete or uMyezane tree was specially reserved, on pain of death, for the Zulu king. From it, little dumbell-shaped beads were cut, which if strung together, formed an interlocking necklace. These beads were given to Zulu warriors who specially distinguished themselves in battle. A warrior wearing a necklace of these beads was regarded with no less respect than a British holder of the VC.

The battles of Isandlwana and Rorke’s Drift were the first two decisive battles of the Anglo-Zulu war. They set the tone for the rest of the war which would last until July 1879. The Zulu success at the Battle of Isandlwana showcased the strength of the Zulu nation and army as well as the overconfidence of the Imperial forces under Lord Chelmsford. But Zulu success was short-lived, their defeat at Rorke’s Drift the first of many.

By March, reinforcements arrived to aid the Imperial army. Several battles and skirmishes ensued, the last being the Battle of Ulundi. The British forces defeated the Zulu army, ultimately ending the war and Zulu control over the region.

King Cetshwayo was later hunted down and captured, the Zulu monarchy was suppressed and Zululand divided into autonomous areas. In 1887, it was declared a British territory, and became part of the British colony of Natal ten years later.

King Cetshwayo was taken to Cape Town where he was imprisoned, first in the Castle, and later under much less-rigorous conditions at Oude Molen, near present-day Pinelands.More than three years were to pass before his eventual return to Zululand. He sailed to England in September 1882 to meet Queen Victoria and on his return, was reinstated as King, but on terms set by the British Government.

King Cetshwayo again settled at Ondini, but his homestead was attacked by Zibhebhu. He was injured and took refuge at Eshowe, where he died on 8 February 1884.

His grave is in a clearing in the Nkandla Forest, and is tended by the Shezi clan. The area is considered to be sacred by the Zulu people.

But what is mainly forgotten,is that as in any battle there are casualties not seen or felt until well after the engagement are was over, in the case of Rorke’s Drift many of the defenders suffered what we now know as PTSD, post traumatic stress, following the battle This was predominantly caused by the fierce close-combat fighting they had with the Zulus.

Most of the rank and file recruits to the British Army were rough and ready lads from labouring or slum backgrounds who had limited options in life. Army life was disciplined and secure and, the occasional tangle with Zulus aside, more secure than the precarious environment and drudgery of civilian life for men of their station. The psychological effects of a brutal battle for survival against huge odds on the men who fought in it can only be imagined. There was no recognition of or tolerance for what was later classified as “battle fatigue” and latterly labeled Post Traumatic Stress. What we do know is that many of the survivors died young. There was at least one confirmed suicide and several who “fell on hard times”.

Take Private Robert Jones, for instance,Wikipedia records that after leaving the army, Jones settled in Herefordshire’s Golden Valley where he became a farm labourer and married Elizabeth Hopkins with whom he had five children. In 1898 Jones died in Peterchurch from gunshot wounds to the head at the age of 41. He had borrowed his employer's shotgun to go crow-shooting. His death certificate records a verdict of suicide whilst being insane.

The coroner heard that he was plagued by recurring nightmares arising from his desperate hand-to-hand combat with Zulus.Despite the accolade of his Victoria Cross the trauma he experienced blighted his life and most likely led to his early death.

Due to the stigma of the time about suicide, when Jones was buried his coffin was reputedly taken over the wall instead of being carried through the church gates into the graveyard and his headstone faces away from the church, the only one in the churchyard to do so.

His gravestone can still be found today in the graveyard at St Peter’s Church, Peterchurch in the Golden Valley; the inscription reflects the fact that his regiment was renamed ‘The South Wales Borderers’ some two years after their action at Rorke’s Drift.

No comments:

Post a Comment