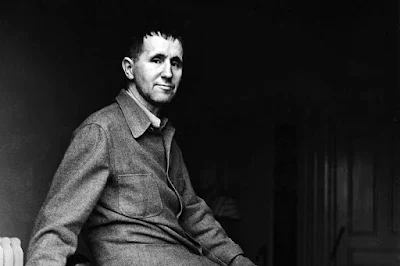

Bertolt Brecht (1898 - 1852) who was born on this day in Ausberg. Germany was a German, Socialist, anti-fascist playwright, theater director and poet.,Born Eugen Berthold Friedrich Brecht in 1898

Brecht was a committed artist who fought for his beliefs; he used his work and art as a form of militancy. He remains an inspiration for people in struggle across the world..

He came from a middle class, religious household The son of a Catholic businessman, Brecht was raised, however, in his mother's Protestant faith. This clash with an authoritarian church may have fed his later ardent support for the underdog.

In 1917 he matriculated at the University of Munich to study philosophy and medicine. In 1918 he served as a medical orderly at a military hospital in Augsburg. The unpleasantness of this experience confirmed his hatred of war and stimulated his sympathy for the unsuccessful Socialist revolution of 1919. Brecht served at the tail end of WWI as a hospital orderly and chafed under the restrictions his duties placed on his writing. From a young age, he guarded his time and took his art quite seriously.

More pivotal than the war for Brecht was the failed German Revolution of 1918-1919. The working class movement was split and the writer supported the Communists. He never wavered in his defense of the Soviet Union. He wrote “Epitaph 1919” about the leader of the German insurrection, Rosa Luxemburg.

Red Rosa now has vanished too,

Where she lies is hid from view.

She told the poor what life is about

And so the rich have rubbed her out.

The themes of opposition to war and sympathy for the working class and its burdens dominate Brecht’s poetry. In “Lullabies” he is a mother speaking of her husband, dead in the war, and her determination to keep her son safe. She addresses her son,

My son, you must listen to your mother when she tells you

It’ll be worse than the plague, the life you’ve got in store.

But don’t think I brought you into the world so painfully

To lie down under it and meekly ask for more.

What you don’t have, don’t ever abandon

What they don’t give you, get yourself and keep.

I, your mother, haven’t borne and fed you

o see you crawl one night under a railway arch to sleep.

The poem ends with words exhorting her son to “stay close to your own people/So your power, like the dust, will spread to every place.”

In 1919 Brecht returned to his studies but devoted himself increasingly to writing plays. His first full-length plays were Baal (1922) and Trommeln in der Nacht (1922; Drums in the Night). In September 1922 Drums in the Night was presented at the Munich Kammerspiele, where Brecht was subsequently employed as resident playwright.

Brecht's early plays, including Im Dickicht der Städte (1923; Jungle of the Cities), are works in which he gradually frees himself from the expressionist conventions of the avant-garde theater of his day, especially its idealism. He parodies and ridicules the lofty sentiments and visionary optimism of his predecessors (Georg Kaiser, Fritz von Unruh, and others) while exploiting their technical advances. Baal portrays the brutalization of all finer feeling by a drunken vagabond. In Drums in the Night, a drama on the returned-soldier theme, the hero rejects the opportunity for a splendid death on the barricades, preferring to make love to his woman. Such cynicism recalls Frank Wedekind, Brecht's most revered model. Jungle of the Cities decries the possibility of spiritual freedom and reasserts the primacy of materialistic values. In these two plays Brecht emphasizes the artificiality of the theatrical medium and disregards conventional psychological motivation.

In 1924 Brecht moved to Berlin and for the next 2 years was associated as a playwright with Max Reinhardt's Deutsches Theater. His comedy Mann ist Mann (1926; A Man's a Man) studies the social conditioning that transforms an Irish packer into a machine gunner and shows a development toward a terser, more intellectual style. By 1926 Brecht had begun a serious study of Marxism.

As a Marxist he became one of the most influential theater practitioners of the 20th century. Brecht's unique approach to theatre, with its emphasis on social and political commentary continues to inspire artists and audiences alike today.

Brecht collaborated with the composer Kurt Weill on Mahagonny (or Kleine Mahagonny), a play with music written for the Baden-Baden festival of 1927. They then wrote Die Dreigroschenoper (1928; The Threepenny Opera), which was triumphantly performed in Berlin on Aug. 31, 1928. This was the first work to make Brecht famous.

Brecht based The Threepenny Opera on Elisabeth Hauptmann's translation of The Beggar's Opera (produced 1728) by the English dramatist John Gay. While adapting and modernizing Gay's balled opera, Brecht retained the main events of the plot but added topical satirical bite through his own lyrics. In this work he develops to its first high point his own special language—that peculiar amalgam of street-colloquial, Marxist-philosophical, and quasi-biblical diction laced with cabaret wit and lyrical pathos and bound together with the unrelenting force of parody. Brecht borrows freely from many sources—among them François Villon and Rudyard Kipling—but his undisguised plagiarism generally supports sharp parody.

Brecht wrote several more plays with music in collaboration with Weill and with Paul Hindemith. Notable are Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny (1929; The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny) and Das Badener Lehrstück vom Einverständnis (1929; The Didactic Play of Baden: On Consent). The latter deals with the issue of "consent"— consent to the extinction of the individual for the sake of the progress of the masses. In Die Massnahme (1930; The Measure Taken), for which Hanns Eisler composed the score, Brecht publicly espouses Communist doctrine and concedes the necessity for the elimination of erring party members. The playwright's love of parody is well illustrated in Die Ausnahme und die Regel (1930; The Exception and the Rule) and in Die heilige Johanna der Schlachthöfe (1932; St. Joan of the Stockyards), in which a Salvation Army girl strives to save the souls of Chicago capitalists.

Saddled with reparations to the Allied -powers that won WWI, Germany was hard hit by the Great Depression. With a fractured left wing and the disastrous Stalin-directed policy of the Communist Party refusing to ally with the reformist German Social Democratic Party (SPD) in the fight against Hitler, the stage was set for his rise. Brecht marked the dictator’s coming with a satirical song, “Hitler Chorale.”

Now thank we all our God

For sending Hitler to us;

From Germany’s fair land

To clear away the rubbish…

In the end, the poet concludes

After long years he’s found you

You’ve reached your goal at last.

The butcher’s arms are round you

He holds you to him fast.

In his poem “When the Fascists Kept Getting Stronger” Brecht talks about fighting back against the right wing.

When the fascists kept getting stronger in Germany

And even workers were joining them in growing masses

We said to ourselves: We fought the wrong way.

All through our red Berlin the Nazis strutted, in fours and fives

In their new uniforms, murdering Our comrades…

So we said to the comrades of the SPD:

Are we to stand by while they murder our comrades?

The SPD was slow to react to increasing attacks against workers.

In a poem titled “To The Fighters in the Concentration Camps,” the poet speaks of the steadfastness of the workers and concludes with,

So you are

Vanished but

Not forgotten

Beaten down but

Never confuted

Along with all those incorrigibly fighting

Unteachably set on the truth

Now and forever the true

Leaders of Germany.

Brecht fled Germany when the Nazis came to power, moving to various countries, and writing several anti-fascist plays. From

1933 to 1948 Brecht was an exile, first in Scandinavia, then in the

U.S.S.R., and after 1941 in the United States. In 1933 his books were

among those publicly burned in Berlin. He continued to write in exile,

and in 1936 he completed Die Rundköpfe und die Spitzköpfe (The Roundheads and the Peakheads) and Furcht und Elend des Dritten Reiches (Fear and Misery of the Third Reich), which directly attacked Hitler's regime.

In 1939 Leben des Galilei (Galileo) opened the sequence of Brecht's great plays; there followed Mutter Courage (1939; Mother Courage), Der gute Mensch von Sezuan (1941; The Good Man of Szechuan), and Der kaukasische Kreidekreis (1943; The Caucasian Chalk Circle). Other important works belonging to this period are Herr Puntila und sein Knecht Matti (1941; Puntila and His Man Matti) and Der aufhaltsame Aufstieg des Arturo Ui (1941; The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui).

These plays demonstrate that Brecht's power and depth as a dramatist

are to a high degree independent of, and even override, his theoretical

principles. They display an astonishing capacity for creating living

characters, a moving compassion, technical virtuosity, and parodic wit. Mother Courage,

a series of scenes from the life of a camp follower during the Thirty

Years War, is often misunderstood because the overwhelmingly vital

portrait of the central character arouses the audience's sympathies. But

Brecht's actual concern was to demonstrate the self-perpetuating folly

of Mother Courage's naive collaboration with the system that exploits

her and destroys her family.

He went to the U.S in 1941, but faced repression as McCarthyist anti-communism heated up. In 1948 he moved to socialist East Germany where he lived until he died of a heart attack in August 1956 at the age of 56. He and his wife, the actress Helene Weigel, founded the Berliner

Ensemble in September 1949 with ample financial support from the state.

This group became the most famous theater company in East Germany and

the foremost interpreter of Brecht.

He wrote the following poem in exile during the early years of the Third Reich in virtue of its title, addressed himself to a posterity he believed, would be unable to understand how it felt to live in a

time of acute moral and political crisis. What defines such a time, he

wrote, is that disaster becomes the only possible subject of thought,

crowding out everything we think of as ordinary life:

“What kind of times are these, when/To talk about trees is almost a crime/Because it implies silence about so many horrors?” Brecht urged his readers to consider the actions of people living in these “dark times,” finsteren Zeiten, with particular sympathy: “When you speak of our failings,” the poem implores, “Bring to mind also the dark times/That you have escaped.”

Entitled An die Nachgebrenen or To Those Born Later in a period he referred to repeatedly as "the dark times." From the perspective of this time of desperation and despair Brecht imagined in his poem a different future a time when "man would be a helper to man"

The dark times sadly are still not over, we still bare witness to a world of global war,poverty, hunger, environmental collapse, the unchallenged reign of capitalism, and far-right groups emerging again to take advantage of the fear among us.

Brecht's words are ever so resonant as we also attempt to imagine a better future and find traces of hope before its too late, his words can still sustain us as we seek ways to escape and resist the politics of division.

These dangerous times require all of us to dig deep into our common humanity. We must build bridges across all boundaries of difference and nonviolently resist all efforts from whatever quarter to dehumanise and demonise the other as is happening all around the world at the present time.

To Those Born Later - Bertolt Brecht

I

Truly, I live in dark times!

The guileless word is folly. A smooth forehead

Suggests insensitivity. The man who laughs

Has simply not yet had

The terrible news.

What kind of times are they, when

A talk about trees is almost a crime

Because it implies silence about so many horrors?

That man there calmly crossing the street

Is already perhaps beyond the reach of his friends

Who are in need?

It is true I still earn my keep

But, believe me, that is only an accident. Nothing

I do gives me the right to eat my fill.

By chance I've been spared. (If my luck breaks, I am lost.)

They say to me: Eat and drink! Be glad you have it!

But how can I eat and drink if I snatch what I eat

From the starving, and

My glass of water belongs to one dying of thirst?

And yet I eat and drink.

I would also like to be wise.

In the old books it says what wisdom is:

To shun the strife of the world and to live out

Your brief time without fear

Also to get along without violence

To return good for evil

Not to fulfill your desires but to forget them

Is accounted wise.

All this I cannot do:

Truly, I live in dark times.

II

I came to the cities in a time of disorder

When hunger reigned there.

I came among men in a time of revolt

And I rebelled with them.

So passed my time

Which had been given to me on earth.

My food I ate between battles

To sleep I lay down among murderers

Love I practised carelessly

And nature I looked at without patience.

So passed my time

Which had been given to me on earth.

All roads led into the mire in my time.

My tongue betrayed me to the butchers.

There was little I could do. But those in power

Sat safer without me: that was my hope.

So passed my time

Which had been given to me on earth.

Our forces were slight. Our goal

Lay far in the distance

It was clearly visible, though I myself

Was unlikely to reach it.

So passed my time

Which had been given to me on earth.

III

You who will emerge from the flood

In which we have gone under

Remember

When you speak of our failings

The dark time too

Which you have escaped.

German; trans. John Willett, Ralph Manheim & Erich Fried

“What kind of times are these, when/To talk about trees is almost a crime/Because it implies silence about so many horrors?” Brecht urged his readers to consider the actions of people living in these “dark times,” finsteren Zeiten, with particular sympathy: “When you speak of our failings,” the poem implores, “Bring to mind also the dark times/That you have escaped.”

Entitled An die Nachgebrenen or To Those Born Later in a period he referred to repeatedly as "the dark times." From the perspective of this time of desperation and despair Brecht imagined in his poem a different future a time when "man would be a helper to man"

The dark times sadly are still not over, we still bare witness to a world of global war,poverty, hunger, environmental collapse, the unchallenged reign of capitalism, and far-right groups emerging again to take advantage of the fear among us.

Brecht's words are ever so resonant as we also attempt to imagine a better future and find traces of hope before its too late, his words can still sustain us as we seek ways to escape and resist the politics of division.

These dangerous times require all of us to dig deep into our common humanity. We must build bridges across all boundaries of difference and nonviolently resist all efforts from whatever quarter to dehumanise and demonise the other as is happening all around the world at the present time.

To Those Born Later - Bertolt Brecht

I

Truly, I live in dark times!

The guileless word is folly. A smooth forehead

Suggests insensitivity. The man who laughs

Has simply not yet had

The terrible news.

What kind of times are they, when

A talk about trees is almost a crime

Because it implies silence about so many horrors?

That man there calmly crossing the street

Is already perhaps beyond the reach of his friends

Who are in need?

It is true I still earn my keep

But, believe me, that is only an accident. Nothing

I do gives me the right to eat my fill.

By chance I've been spared. (If my luck breaks, I am lost.)

They say to me: Eat and drink! Be glad you have it!

But how can I eat and drink if I snatch what I eat

From the starving, and

My glass of water belongs to one dying of thirst?

And yet I eat and drink.

I would also like to be wise.

In the old books it says what wisdom is:

To shun the strife of the world and to live out

Your brief time without fear

Also to get along without violence

To return good for evil

Not to fulfill your desires but to forget them

Is accounted wise.

All this I cannot do:

Truly, I live in dark times.

II

I came to the cities in a time of disorder

When hunger reigned there.

I came among men in a time of revolt

And I rebelled with them.

So passed my time

Which had been given to me on earth.

My food I ate between battles

To sleep I lay down among murderers

Love I practised carelessly

And nature I looked at without patience.

So passed my time

Which had been given to me on earth.

All roads led into the mire in my time.

My tongue betrayed me to the butchers.

There was little I could do. But those in power

Sat safer without me: that was my hope.

So passed my time

Which had been given to me on earth.

Our forces were slight. Our goal

Lay far in the distance

It was clearly visible, though I myself

Was unlikely to reach it.

So passed my time

Which had been given to me on earth.

III

You who will emerge from the flood

In which we have gone under

Remember

When you speak of our failings

The dark time too

Which you have escaped.

German; trans. John Willett, Ralph Manheim & Erich Fried