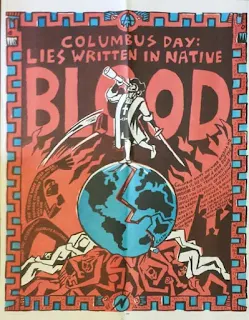

Christopher Columbus arrived in the Bahamas 528 years ago this week,

beginning a

process of colonization and genocide against Native people, which

represents one of the darkest chapters in the history of this continent,

that unleashed unimaginable brutality against the indigenous people of this

continent.that killed tens of millions of Native

people across the hemisphere. From the very beginning, Columbus was not on a mission of discovery but of conquest and exploitation—he called his expedition la empresa, the enterprise.

Columbus deserves to be remembered as the first terrorist in the

Americas. When resistance mounted to the Spaniards’ violence, Columbus

sent an armed force to “spread terror among the Indians to show them how

strong and powerful the Christians were,” according to the Spanish

priest Bartolomé de las Casas. In his book Conquest of Paradise,

Kirkpatrick Sale describes what happened when Columbus’s men

encountered a force of Taínos in March of 1495 in a valley on the island

of Hispañiola: " The soldiers mowed down dozens with

point-blank volleys, loosed the dogs to rip open limbs and bellies,

chased fleeing Indians into the bush to skewer them on sword and pike,

and [according to Columbus’s biographer, his son Fernando] “with God’s

aid soon gained a complete victory, killing many Indians and capturing

others who were also killed.”

All this and much more has long been known and documented. As early as 1942 in his Pulitzer Prize winning biography, Admiral of the Ocean Sea,

Samuel Eliot Morison wrote that Columbus’s policies in the Caribbean

led to “complete genocide”—and Morison was a writer who admired

Columbus.

Many countries are now

acknowledging this devastating history by rejecting the federal holiday

of Columbus Day which is marked on October 12 and celebrating Indigenous Peoples’ Day instead to honor

centuries of indigenous resistance.If Indigenous peoples’ lives mattered in our society, and if Black

people’s lives mattered in our society, it would be inconceivable that

we would honor the father of the slave trade with a national holiday. Let alone allow our history books to laud Columus as some kind of hero. For oppressed people this day is a constant reminder that many of their ancestors and their suffering simply did not matter. As a result many countries in the Americas now celebrate

October 12 as Día de la Raza and many indigenous peoples and other

progressive people celebrate it as Indigenous People's Day or Indigenous

Resistance Day. Because this

so-called “discovery” of the America caused the worst demographic

catastrophe of human history, with around 95 percent of the indigenous

population annihilated in the first 130 years of colonization, without

mentioning the victims from the African continent, with about 60 million

people sent to the Americas as slaves, with only 12 percent of them

arriving alive.Therefore, Native American groups consider Columbus a

European colonizer responsible for the genocide of millions of

indigenous people. Not an individual worthy of celebration because he

helped contribute to the Europeans Colonization of the Americas which

resulted in slavery, killings, and other atrocities against the native

Americans

As a counter to official celebrations of "Columbus Day" with indigenous people increasingly demanding their rights, in 1992 the United Nations declared October 12 as the International Day of Indigenous Peoples, ruining thereby the determination of Spain and other countries to call it International Day of America's Discovery, this was then followed by Venezuela which was the first country of the region to grant the demand under Hugo Chavez's administration, accepting their suggestion of “Day of Indigenous Resistance” in 2002. Chavez described the previous name “Day of Race” chosen by then President of Venezuela, Juan Vicente Gomez in 1921, as “discriminatory, racist and pejorative.”

Nicaragua and Daniel Ortega´s Sandinista government has been the only country going as far as Venezuela until now, also choosing the name “Day of Indigenous Resistance” in 2007.

With several exceptions, such as the conservative governments of Paraguay, Colombia and Honduras, for instance, many other countries of the continent have nevertheless changed the infamous name “Day of Race.”

It became the “Day of Respect for Cultural Diversity” in Argentina, after the failure of a legislative project in 2004 to change it to “Day of Resistance of Indigenous Peoples.” Argentina has more than 1,600 indigenous communities, and over a million Argentinian people who claim their indigenous identity according to the National Institution of Indigenous People.Yet the indigenous communities of Argentina organize counter-marches to protest against this name, recalling the damages caused by the conqueror Julio Argentino Roca to their ancestral lands at the end of the 19th century.

In Chile as well, where the Mapuche community are still fighting to claim their native lands in the fertile south of the country, the day was renamed even more weakly, “Day of the Encounter Between the Two Worlds” in 2000.

In Ecuador, President Rafael Correa changed the name to “Day of Inter-culturality and Pluri-nationality” in 2011. That same year in Bolivia, President Evo Morales, the first indigenous leader in South America, changed it to "Day of Mourning for the Misery, Diseases and Hunger Brought by the European Invasion of America." The diseases were indeed the main cause of the indigenous genocide, as the invaders brought viruses and bacterias the indigenous peoples were not immune to.

In El Salvador, social and indigenous organizations presented a legislative project before the parliament, for which the congresspeople of the governing Farabundo Marti Front (FMLN) expressed their support. In June 2014, the congress finally approved a constitutional reform recognizing the existence of indigenous peoples in the country. In 2016, Salvadorean and Uruguayan indigenous peoples began demanding a name change of their governments. The Charrua community of Uruguay for instance has made the demand since 2010, but has faced strong opposition by conservative sectors. In 2014, the National Assembly approved a legislative project, but only changed the name to “Day of Cultural Diversity.” The ruling party Broad Front (Frente Amplio) had pushed for the same name as in Venezuela and Nicaragua, but the legislative commission then chose to modify it.

As a counter to official celebrations of "Columbus Day" with indigenous people increasingly demanding their rights, in 1992 the United Nations declared October 12 as the International Day of Indigenous Peoples, ruining thereby the determination of Spain and other countries to call it International Day of America's Discovery, this was then followed by Venezuela which was the first country of the region to grant the demand under Hugo Chavez's administration, accepting their suggestion of “Day of Indigenous Resistance” in 2002. Chavez described the previous name “Day of Race” chosen by then President of Venezuela, Juan Vicente Gomez in 1921, as “discriminatory, racist and pejorative.”

Nicaragua and Daniel Ortega´s Sandinista government has been the only country going as far as Venezuela until now, also choosing the name “Day of Indigenous Resistance” in 2007.

With several exceptions, such as the conservative governments of Paraguay, Colombia and Honduras, for instance, many other countries of the continent have nevertheless changed the infamous name “Day of Race.”

It became the “Day of Respect for Cultural Diversity” in Argentina, after the failure of a legislative project in 2004 to change it to “Day of Resistance of Indigenous Peoples.” Argentina has more than 1,600 indigenous communities, and over a million Argentinian people who claim their indigenous identity according to the National Institution of Indigenous People.Yet the indigenous communities of Argentina organize counter-marches to protest against this name, recalling the damages caused by the conqueror Julio Argentino Roca to their ancestral lands at the end of the 19th century.

In Chile as well, where the Mapuche community are still fighting to claim their native lands in the fertile south of the country, the day was renamed even more weakly, “Day of the Encounter Between the Two Worlds” in 2000.

In Ecuador, President Rafael Correa changed the name to “Day of Inter-culturality and Pluri-nationality” in 2011. That same year in Bolivia, President Evo Morales, the first indigenous leader in South America, changed it to "Day of Mourning for the Misery, Diseases and Hunger Brought by the European Invasion of America." The diseases were indeed the main cause of the indigenous genocide, as the invaders brought viruses and bacterias the indigenous peoples were not immune to.

In El Salvador, social and indigenous organizations presented a legislative project before the parliament, for which the congresspeople of the governing Farabundo Marti Front (FMLN) expressed their support. In June 2014, the congress finally approved a constitutional reform recognizing the existence of indigenous peoples in the country. In 2016, Salvadorean and Uruguayan indigenous peoples began demanding a name change of their governments. The Charrua community of Uruguay for instance has made the demand since 2010, but has faced strong opposition by conservative sectors. In 2014, the National Assembly approved a legislative project, but only changed the name to “Day of Cultural Diversity.” The ruling party Broad Front (Frente Amplio) had pushed for the same name as in Venezuela and Nicaragua, but the legislative commission then chose to modify it.

Indigenous

peoples in Latin America account for about 13 percent of the total

population – about 40 million, with around 670 different nations or

communities, according to the CEPAL. Most of them are in Mexico,

Guatemala, and Andean countries. They all face some level of racism,

discrimination and poverty, suffering more than the rest of the

population from an unequal access to resources like employment, health

and education services, but also deprived of their ancestral lands and

natural resources – about 40 percent of rural populations are

indigenous, according to the International Work Group for Indigenous

Affairs.https://www.iwgia.org/en/

Since the outbreak of COVID-19

in the United States, Indigenous people have experienced some of the

highest mortality rates in the county. High rates of diabetes, obesity

and other poverty-related health problems make Native Americans more

vulnerable to the virus than other populations.

The Navajo Nation, which spreads across Arizona, New Mexico and Utah, has been one of the hardest hit locations .Due to pollution caused by mining and lack of basic infrastructure, about 40 perceent

of those who live on the Navajo Nation lack access to drinking water

and haul water or rely on water trucks. This lack of clean, running

water makes it nearly impossible for Navajo people to follow Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention guidance to constantly wash their hands

and surfaces.

In Mississippi, rates of COVID are 10 times higher among the Mississippi Choctaw,

the only federally recognized Native nation in the state, than among

the rest of Mississippi’s population. So far, more than 1,000 people or

more than 10 percent of all Mississippi Choctaws have contracted

coronavirus, and many have lost multiple family members.

Exacerbating the crises within

Indigenous communities across North America, the Trump administration’s

border wall and immigration policies have caused further devastation

to many Native communities. Thousands of migrants, including many who

are from Indigenous communities within Central America, have been

exposed to the virus in U.S. detention

centers. By housing migrants in these dense holding centers—without

proper medical care, sanitation or personal protective equipment, and

then deporting them—U.S. immigration practices have exported the virus to Indigenous communities across Guatemala and Mexico.

The border wall and these

immigration policies have brought further violence and risk of exposure

to Native nations whose homelands straddle the U.S.-Mexico border.

Native nations like the Kumeyaay in California and the Tohono O’odham,

whose lands stretch between Arizona and the Mexican state of Sonora,

have fought for years against the construction of Trump’s border wall

through their lands. Within the last month, multiple Kumeyaay and Tohono

O’odham demonstrators have been arrested

and forcibly removed from their own homelands as they attempted to halt

construction of the wall and protect their sacred lands.

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, author of “An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States,” writes, “By

and large the history of relations between Indigenous and settler is

fraught with conflict, defined by a struggle for land, which is

inevitably a struggle for power and control. Five hundred years later,

Native peoples are still fighting to protect their lands and their

rights to exist as distinct political communities and individuals.”

Because of historical traumas inflicted on indigenous peoples that include land

dispossession, death of the majority of the populations through warfare

and disease, forced removal and relocation, assimilative boarding school

experiences, and prohibiting religious practices, among others, indigenous peoples have experienced

historical losses, which include the loss of land, traditional and

spiritual ways, self-respect from poor treatment from government

officials, language, family ties, trust from broken treaties, culture,

and people (through early death); there are also losses that can be

attributed to increased alcoholism.

These losses have been associated with sadness and depression, anger,

intrusive thoughts, discomfort, shame, fear, and distrust around white

people Experiencing massive traumas and losses is thought to lead to cumulative and unresolved grief, which can result in the historical trauma response,

which includes suicidal thoughts and acts, IPV, depression, alcoholism,

self-destructive behavior, low self-esteem, anxiety, anger, and lowered

emotional expression and recognition .These symptoms run parallel to the extant health disparities that are documented among indigenous peoples.

Today is about acknowledging all this whilst honoring the rich history of resistance that Native

communities across the world have contributed to and it is also

about sharing a deep commitment to intergenerational justice. Celebrating Indigenous People’s Day is a step towards recognizing that

colonization still exists. We can do more to end that colonization and respect

the sovereignty of indigenous nations. .May we spend this

day, and all days, honoring Native Peoples’ commitment to making the

world a better place for all. Reflect on their ancestral past , the ongoing struggles of indigenous peoples in protecting their lands and freedoms,celebrate their sacrifices and celebrate life whilst.recognizing the

people, traditions and cultures that were wiped out because of Columbus’

colonization and acknowledge the. bloodshed and elimination of

those that were massacred.Transforming this day into a

celebration of indigenous people and a celebration of social justice

allows us to make a connection between this painful history and the

ongoing marginalization, discrimination and poverty that indigenous

communities face to this day.