Wednesday, 8 August 2018

The Ballad of Mairéad Farrell - Seanchai and The Unity Squad, with vocals by Rachel Fitzgerald

On a quiet Sunday afternoon in Gibraltar on March 6, 1988 ,undercover British agents executed 3 members of an unarmed Provisional IRA unit, Sean Savage, Dan McCann and Mairéad Farrell shot.at close range as they lay wounded on the ground.

Their deaths were controversial as several eye witnesses confirmed that they were all were unarmed and with their hands up,The three were believed at the time to be mounting a bombing attack on British military personnel in Gibraltar.

What is undeniable is that just before four that afternoon – just two or three minutes after SAS soldiers took control from the Gibraltar authorities – all three IRA Activists were brought down in a hail of 29 bullets, 16 pumped into Savage alone. A police siren sounded, and two soldiers leaped over a barrier as Farrell and McCann lay dying in the road leading to the Spanish border. A few seconds later and another volley of shots brought down Savage as he headed up an alleyway back towards the town.

The gunning down of three unarmed IRA Activists on the streets of Gibraltar by the SAS has continued to haunt the British government. The March 1988 executions led to a cycle of death in the north of Ireland, re-opened claims that the government operated a ‘shoot-to kill’ policy and, yet again, called into question the reputation of British justice.

The British media at the time with the exception of Thames TVs Death on the Rock", repeated the British Army propoganda that the three were armed and the local eyewitness were lying. At the inquest into the deaths held in Gibraltar the jury returned a verdict of lawful killing by a 9–2 majority. The coroner in summing up of the evidence to the jury told them to avoid an open verdict. The 9-2 verdict is the smallest majority allowed. Paddy McGrory, lawyer for Amnesty International, believed that it had been a "perverse verdict," and that it had gone against the weight of the evidence.

The relatives of McCann, Savage and Farrell were dissatisfied with the response to their case in the British legal system, so they took their case to the European Court of Human Rights in 1995. The court found that the three had been unlawfully killed By a 10–9 majority it ruled that the human rights of the 'Gibraltar Three' had been infringed in breach of Article 2 – right to life, of the European Convention on Human Rights and criticised the authorities for lack of appropriate care in the control and organisation of the arrest operation. For many it was cold state-sanctioned murder, at point blank range.

When the bodies came through Dublin Airport, all the staff stopped with their heads bowed and prayed as a mark of respect.

There was also shock at the time as to how a woman like Mairead could have become involved with the IRA. To Mairead, however her membership was a logical decision made as a result of a political analysis drawn from both political experience and a study of Irish history,

Mairead was born in Belfast on the 3rd August 1957, the second youngest of six children and the only girl. She was twelve when the British Army took over the streets of Belfast in 1969. This subsequently led to her being politicized.

" It was relavent of growing up in the Falls, we had to pass the Brits during the curfews you could only get out for a certain number of hours. We were all victims of the British occupation really you just accepted that you would be involved to defend your country. " She joined the IRA and said later, "A lot of 17 to 19 year olds were involved, maybe looking back I was very young then but I was politically aware I know rhat now because my views haven't changed if anything I have become stronger, more committed. "

In 1976 she was arrested after taking part in the IRA's campaign. She was convicted of possesion of explosives and membership of the IRA and sentenced to fourteen and a half years imprisonment. Mairead was sentenced at a crucial turning point in British policy and was to become the leader of the women in Armagh jail when the republican struggle was focussed on the prisoners.

When Mairead entered Armagh in April 1976 she was the first woman republican prisoner to be sentenced under the new regulations and was refused special category status. She was isolated from the Republican organization in Armagh and only able to talk to the other fifty or so republican women for ten minutes after Mass on Sundays. She began a “no work protest” against the loss of special category status, “I knew now the battle would begin - the real battle - that the struggle would be a long and lonely one for us all

As other newly sentenced women entered Armagh they joined Mairead in protests. Mairead became Commanding Officer. ‘There was no kudos in it, I had to take decisions that would effect all the prisoners. There were times I felt very alone, even though I knew I had the support of the others at all times.’

The dirty protest that began on 7th February 1980 was forced on Mairead and her comrades. The Republican women were able to wear their own clothes; they were all dressed in black skirts and white blouses at a ceremony to honour Delaney. A week later, to crush this example of organised solidarity, a squad of 60 male and female warders surrounded the women at lunch time. Tim Pat Coogan stated that the women “were kicked and punched until order was restored’ Their cells were searched and wrecked by the warders and after the women were returned to their cells, “Men in riot gear armed with batons appeared in the cells again. The girls (sic) were beaten and carried down the stairs to the guard room to receive their punishment. The toilets were locked and they were confined to their cells for 24 hours.’

Mairead described the events to her parents: We were not allowed exercise nor out to the toilet or to get washed. We were locked up for 24 hours and allowed nothing to eat or drink. Male officers are still on the wing, they have not left and are running the wing got something to eat still not allowed use of toilet facilities. We have been forced into a position of “Dirt Strike’ as our pots are overflowing with urine and excrement. We emptied them out of the spy holes into the wing. The male officers nailed them closed.” Then later: ‘Male officers are still running the wing Lynn O’Connell was beaten twice, the second time was the worst. The officers jumped her as she was going out to the yard her face is badly swollen and cut.’

In early April 1980 Mairead wrote to her relatives, “The stench of urine and excrement clings to the cells and our bodies. No longer can we empty the pots out the window as the male screws have boarded them up regardless of day or night, the cells are dark for 23 hours a day we lie in these celIs’ The protest lasted 13 months. It was to Mairead the most frightening time of her imprisonment. Women were locked in pairs in cells measuring 3m x 2m (9ft x 6ft). During this time, Mairead told Tim Pat Coogan, “We are in a war situation. We have been treated in a special way and tried in special courts because of the war and because of our political activities. We want to be regarded as prisoners of war.

On 1st December 1980, Mairead, Mary Doyle and Mairead Nugent went on hunger strike in united action with the men in the Long Kesh ‘H Blocks. Afterwards she recalled how important was the support received from outside and also how she hated the distress caused to her parents. She continued on hunger strike until 19th December when it seemed the N.I.O. had agreed to the prisoners’ demands. This agreement was then retracted.

The Dirty Protest was called off in January 1981 in preparation for the second hunger strike in the H Blocks on 1st March 1981. A difficult decision not to join this was made by the women prisoners. It was the worst time for them as the women waited for news of the deaths, “I know it will be more difficult this time to win anything. It will take longer for the pressure to build up.” At the end of the interview Mairead said, “I am a volunteer in the Irish Republican Army and a political prisoner in Armagh jail. I am prepared to fight to the death, if necessary, to win the recognition that I am a political prisoner and not a criminal.’

In December 1982 strip searching was introduced at Armagh. The women republican prisoners refused to undergo these searches that were made before women were allowed out of the prison. Her last inter-prison visit to see her fiancee in Long Kesh was in October 1982 and she did not see him again until her release four years later. The remand prisoners suffered most from strip searching as they were searched before and after court hearings and were subject to regular beatings. The women republican prisoners ended their resistance to strip searching because of the fear of increasingly serious assaults. Mairead was strip searched on her release from Maghaberry Prison, “I felt it was the final insult. It’s designed as psychological torture, as a way of intimidating us.” Looking back on years in prison she saw them as teaching her the real values in life and making her more committed to her political beliefs.

During her last years of imprisonment, Mairead took Open University courses in Politics and Economics, and gained a place at Queen’s University on her release. She worked with the Strip Searching Campaign, speaking at meetings all over Ireland. She then reported back to the IRA. Just before her death she said, “You have to be realistic, you realise that ultimately you’re either going to be dead or end up in jail.”

“Everybody keeps telling me I’m a feminist. I just know I’m me and I think I’m as good as anyone else and that particularly goes for any man. I’m a socialist, definitely, and I’m a republican. I believe in a united Ireland; a united socialist Ireland, definitely socialist. Capitalism provided no answer at all for our people and I think that’s the Brit’s main interest in Ireland. Once we remove the British that isn’t it, that’s only the beginning.”

When their bodies came through Dublin Airport, in the aftermath of the shooting all the staff stopped with their heads bowed and prayed as a mark of respect, following these events violenc would escalate in the Belfast area and resulted in at least six further deaths. At the funeral of the 'Gibraltar Three' on 16 March 1988, three mourners were killed in a gun and grenade attack by loyalist paramilitary Michael Stone in the Milltown Cemetery attack.

After Mairéad''s death it would lead to this hauntingly beautiful tribute “The Ballad of Mairéad Farrell”, by Seanchai and The Unity Squad, with vocals by Rachel Fitzgerald. In 2008 Sinn Féin asked to hold an International Women's Day event in the Long Gallery at Stormont commemorating Farrell. The Assembly Commission which runs the Stormont estate ruled that it could not go ahead. Heroine or villainess, she remains an interesting human being. To the people of Falls Road she was a patriot. To the British she was a terrorist. To her family she was a victim of Irish history and a product of her environment.This elegy, this song and this history to this day has a sort of tragic, beautiful complexity to it.

Do not stand at my grave and weep

I am not there I do not sleep

Do not stand at my grave and cry

while Ireland lives I do not die

A woman's place is not at home

The fight for freedom it still goes on

I took up my gun until freedoms day

I pledged to fight for the IRA

In Armagh jail i served my time

Strip searches were a British crime

Degraded me yet they could not see

I'd suffer this to see Ireland free

Gibraltar Rock was the place I died

McCann and Savage were by my side

I heard the order so loud and true

Of Thatcher's voice said "SHOOT TO KILL"

So do not stand at my grave and weep

I am not there I do not sleep

Do not stand at my grave and cry

While Ireland lives I do not die

While Ireland lives I do not die

Monday, 6 August 2018

Hiroshima Day- Never Again

Sadako and the Crane statue (Hiroshima Memorial Peace Park, Japan)

73 years ago, on 6th August 1945, at 8:15 AM the United States dropped an atomic bomb called “Little Boy” on Hiroshima, which is estimated to have killed 100,000 to 180,000 people out of a population of 350,000. Three days later, a second atomic bomb was dropped on the city of Nagasaki, killing between 50,000 and 100,000 people.an atomic bomb was detonated over Hiroshima. Today, 73 years later, the world commemorates the lives that were lost and the unacceptable devastation caused to people and planet.

A survivor of the Hiroshima bombing gave this harrowing account:

"Through a darkness like the bottom of Hell I could hear the voices of the other students calling for their mothers. I could barely sense the fact that the students seemed to be running away from that place. (...) At the base of the bridge, inside a big cistern that had been dug out there, was a mother weeping and holding above her head a naked baby that was burned bright red all over its body, and another mother was crying and sobbing as she gave her burned breast to her baby. In the cistern the students stood with only their heads above the water and their two hands, which they clasped as they imploringly cried and screamed, calling their parents. But every single person who passed was wounded, all of them, and there was no one to turn to for help. The singed hair on people's heads was frizzled up and whitish, and covered with dust - from their appearance you couldn't believe that they were human creatures of this world".

In the current dangerous times today we must redouble our efforts to ensure that such an atrocity does not happen ever again. It should be unthinkable that the horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki should ever be repeated, on this poignant anniversary, we must reaffirm our determination to campaign for a world without nuclear weapons

For years the American government refused to release images and photographs, such was the sheer horror that they did not want the world to Know.

Those who did not get incarcented on the spot, were to be traumatised for the rest of their lives.

Hibakusha is a term widely used in Japan, that refers to the victims of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it translates as 'explosion effected/ Survivor of the Light. This post is dedicated to them , we should make sure that the devastation caused by nuclear weapons is never forotten.

Please sign following petition :- https://cnduk.org/actions/time-stop-trident/

Hiroshima; An Acrostic Poem

Horror was dropped on August 6, 1945

Incinerating thousands of innocents

Reason evaporated after deadly poison shed

One bomb released left devastaion

Senseless slaughter, the scorched sin of humanity

Haunting vapors of pitiful sorrow

Insanity blossoming with black rain

Murderous atoms shattered spirits

American weapon of evil, B-29 Enola Gay

Hiroshima; An Acrostic Poem

Horror was dropped on August 6, 1945

Incinerating thousands of innocents

Reason evaporated after deadly poison shed

One bomb released left devastaion

Senseless slaughter, the scorched sin of humanity

Haunting vapors of pitiful sorrow

Insanity blossoming with black rain

Murderous atoms shattered spirits

American weapon of evil, B-29 Enola Gay

Thursday, 2 August 2018

Tommy Robinson same shit different arsehole

Apologies for language above but in recent weeks we've seen the biggest far right demonstrations on the streets of the UK in decades, in support of one Stephen Christopher Yaxley-Lennon ( who goes by the name "Tommy Robinson ") With support and funding from the "alt-right" in the United States and the ethno- nationalist Generation Identity movement, whose leaders have been prevented from entering the UK,"Robinson" is reaching millions in the UK through social media with his vitriolic Islamophobic and anti-migrant message. And the Tories not only emulate their policies, from the hostile environment to go home vans -they'e actually meeting with "Alt-right " leaders like Steve Bannon. This far-right strategist actually called Lennon the "backbone" of Britain and is no no doubt hoping to make him a core part of his new 'movement, using him as a front man to increase divisions and stoke anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim anger across Europe.

Lennon has recently been released from prison, he and his allies claim him as a free speech martyr, some supporters chracterise him as a journalist exposing crime, but his social media broadcasts rely on information from the local and national "mainstream" media and tend to cover cases that have already been prosecuted. Lennon having previously broadcast his activities on Twitter, but was permanently banned from the platform earlier this year.He co-founded the EDL (English Defence League) in 2009 and has been arrested numerous times for acts of violence, as well as being jailed for mortgage fraud in 2014.

Earlier this year the former head of national counter-terrorism policing hit out at Lennon's "dangerous disinformation and propoganda" Mark Rowley said that Lennon attacks the whole religion of Islam by conflating acts of terrorism with the faith often citing spurious claims, which inevitably stir up tensions"

"Such figures represented no more than the extreme margins of the communities they claim to speak for, yet they have been given prominence and a platform to espouse their dangerous disinformation and propoganda," he added.

Lennon remains an Islamaphobe with a history of violence and someone who uses intimidation against his opponents. His tactics reveal or expose nothing the courts and legal system have not already exposed. Lest we forget he remains silent about serious sexual abusers within the English Defence League while ranting against muslims.

It's time we woke up to the real Tommy Robinson and his allies, because the fascists are marching again, the fascists are targetting again, the fascists are growing again, and the prospects of fascist politics spreading further their nasty brand of hate is a very real nightmare scenario indeed, its time to confine them again to history's dustbin, so their dangerous ideas never again see the light of day. No pasaran. They shall not pass.

Earlier post here https://teifidancer-teifidancer.blogspot.com/2018/05/the-trouble-with-tommy-robinson.html

Wednesday, 1 August 2018

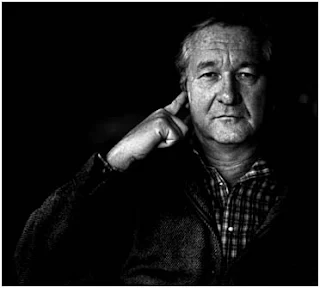

Theodore Roethke (25/4/1908-1/8/63) - In a Dark Time

The following poem by Theodore Roethke seems even more powerful to me today than when I first read it. Throughout his adult life this brilliant Pulitzer award winning poet suffered from manic depression, which actually fueled his writing and actually made him more productive. But combined with a lack of self-esteem and a tendency to turn more and more to drink, plus lots of other factors in his life it would contribute to several notable nervous breakdowns over the years.

Although it speaks of depression In a Dark Time also speaks of a self-discovery, a reawakening. Often we lose ourselves in our despair and abandon all hope, but the loss of the most important things in life can also act as catalysts that give way to insights that have the ability to enrich our future lives. Sometimes in such moments of despair, it is only then that we can discover our true selves, and as time tests us, we can find out who we are and what we truly believe. And although the poem comes with no happy ending, and he is not out of the darkness, he is nevertheless still searching, not quite given up on hope. Sadly on this day, which adds more poignancy, whilst taking a dip in a friend's swimming pool, Theodore had a heart attack and died. He was just 55 years old.

This poem however is one of those poems I like to keep close to in difficult times, in it he manages to create something powerful that connects readers to their own self-doubts and struggles of finding ones way again. Remember those dark periods most of us experience, they actually can serve a purpose, transforming, releasing compassionate hearts, readying for the blaze of light. ' In a dark time, the eye begins to see.'

In a Dark Time - Theodore Roethke

In a dark time, the eye begins to see,

I meet my shadow in the deepening shade;

I hear my echo in the echoing wood--

A lord of nature weeping to a tree.

I live between the heron and the wren,

Beasts of the hill and serpents of the den.

What's madness but nobility of soul

At odds with circumstance? The day's on fire!

I know the purity of pure despair,

My shadow pinned against a sweating wall.

That place among the rocks--is it a cave,

Or a winding path? The edge is what I have.

A steady storm of correspondences!

A night flowing with birds, a ragged moon,

And in broad day the midnight come again!

A man goes far to find out what he is--

Death of the self in a long, tearless night,

All natural shapes blazing unnatural light.

Dark, dark my light, and darker my desire.

My soul, like some heat-maddened summer fly,

Keeps buzzing at the sill. Which I is I?

A fallen man, I climb out of my fear.

The mind enters itself, and God the mind,

And one is One, free in the tearing wind.

Sentencing of Palestinian Poet Dareen Tatour to Five Months in Prison Unjustly Criminalizes Free Expression

Tatour, a Palestinian citizen of Israel from the village Al-Reineh near Nazareth, has been writing poetry since she was 7, She is also a photographer, who has has toured villages in present-day Israel that were depopulated of their original Palestinian inhabitants during the Nakba, As well as capturing images of these villages, she has set out to tell stories about the people who lived in them.

Her photographs have been displayed in a number of exhibitions. She also directed a short documentary about the ethnically cleansed village of Damoun. The Latest Invasion, her first collection of poems, was published in 2010. Her second collection, The Atlantic Canary Tales, addressing women’s issues was due to be published in December 2015, but her arrest at her family home in the early hours of October 11, 2015 prevented that. In addition, Tatour has written another book about her detention waiting for publication.

In a brief statement sent to Jewish Voice for Peace on 11 July of last year Tatour explained the effect that her imprisonment has had on her work.

“The poem, if it remains on paper, only adds to its writer’s worries and fatigue. The worst thing that can happen to an artist in general, and a poet in particular, is to be imprisoned in the democratic era in which we live for expressing their opinion,” Tatour writes.

“Imprisonment is tantamount to cutting the cords of feelings and emotions whose letters connect between what they are writing and the people,” she adds, “and if this communication is cut there is no value to all to what is written by this poet, no matter how outstanding their style. Actually there is no value and meaning to the human existence of the individual in this democracy and basically no value to this democracy.”

“My freedom, after nine months of harsh detention and exile, is a guarantee to the endurance of freedom for every poet, writer and artist, wherever they are,” she added..

Award-winning poet, songwriter, and novelist, Naomi Shihab Nye, referred to the way Tatour’s use of the word “resistance” has been criminalized: “The word “resist” – when it is resisting oppression and inequality – will always be a gleaming, beautiful, positive word. In fact, it needs to be said more often.”

Resist, my My people, Resist them

Resist, my people, resist them.

In Jerualem, I dread my wounds and breathed my sorrows

And carried the soul in my palm

For an Arab Palestine.

I will not succumb to the "peaceful solution,"

Never lower my flags

Until I evict them from my land

I cast them aside for a coming time

Resist , my people, resist them.

Resist the settler's robbery

And follow the caravan of martyrs.

Shred the digraceful contitution

Which imposed degradation and humiliation

And deterred us from restoring justice.

They burned blameles children;

As for Hadil, they niped her in public,

Killed her in broad daylight.

Resist, my people, resist them,

Resist the colonialist's onlaught.

Pay no mind to his agents among us

Who chain us with peaeful illusion.

Do not fear doubtful tonques;

The truth in your heart i stronger,

As long a you resist in a land

That has lived through raids and victory.

So ali called from his grave:

Resist, my rebellious people.

Write me as prose on the agarwoood;

My remain have you as a response.

Resist, my people, resist them.

Resist, my people resist them

Literary expert Prof. Nissim Calderon testified on Tatour’s behalf that poets should have a special privilege to speak freely, even when advocating violence, and argued that canonical Israeli Hebrew poets had written much worse verse.

The defense also argued that Israeli Police statistics show that Jewish Israelis who post explicit calls for violence against Arabs and Palestinians on social media – including the phrase “death to Arabs” – are not similarly arrested and tried.

“There is serious discrimination here,” Lasky said. “If she was Jewish, there would be no case.”

The verdict will have a chilling effect on freedom of speech, Lasky added, and will cause writers to censor themselves. “This decision establishes a clear precedent that criminalizes poetry.”

“The poem was written from the victim’s perspective. It deals with resistance against violence and occupation and does not call for violence itself,” said Dr. Yoni Mendel, an expert in Arabic and a researcher at the Van Leer Jerusalem Institute who also testified at Tatour’s trial.

“The phrase ‘follow the caravan of martyrs,’ which was the basis for the prosecution’s case, was translated to Hebrew as ‘follow the caravan of shahidim,’” Mendel said, “as if it were a call for violence against innocent people. But in fact, the only two shahidim mentioned in the poem are the children Muhammad Abu Khdeir and Ali Dawabshe, who are both Palestinians murdered by Jewish extremists – the farthest that could be from Palestinians killed while trying to harm Israelis.”

Despite holding Israeli citizenship, Palestinians in Israel lived under a military administration between 1948 and 1967 and faced curfews, severe restrictions on free speech and political rights, and persecution in front of military courts.

The recent passage of the "nation state" law earlier this month has caused outrage for enshrining Israel's Jewish identity in the Basic Law - Israel's equivalent of a constitution - a move critics have slammed as further cementing a two-tier ethnic system in Israeli law.

But many Palestinian citizens of Israel have been unsurprised by the new law, pointing to pre-existing discrimination both on the ground and in law, effectively making them second-class citizens when compared to their Jewish peers.

“I never expected justice from the Israeli courts,” Tatour said in response to the verdict. “I knew that I would be convicted of the accusations… I will… keep writing.” Here is her response to the BBC World Service just hours before her sentence https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p06g60kc .At the moment Tatour's lawyers plan to appeal the verdict.

I interrogated my soul

during moments of doubt and distraction:

“What of your crime?”

Its meaning escapes me now.

I said the thing and

revealed my thoughts;

I wrote about the current injustice,

wishes in ink,

a poem I wrote…

The charge has worn my body,

from my toes to the top of my head,

for I am a poet in prison,

a poet in the land of art.

I am accused of words,

my pen the instrument.

Ink— blood of the heart— bears witness

and reads the charges.

Listen, my destiny, my life,

to what the judge said:

A poem stands accused,

my poem morphs into a crime.

In the land of freedom,

the artist’s fate is prison.

during moments of doubt and distraction:

“What of your crime?”

Its meaning escapes me now.

I said the thing and

revealed my thoughts;

I wrote about the current injustice,

wishes in ink,

a poem I wrote…

The charge has worn my body,

from my toes to the top of my head,

for I am a poet in prison,

a poet in the land of art.

I am accused of words,

my pen the instrument.

Ink— blood of the heart— bears witness

and reads the charges.

Listen, my destiny, my life,

to what the judge said:

A poem stands accused,

my poem morphs into a crime.

In the land of freedom,

the artist’s fate is prison.

- Excerpt from A Poet Behind Bars by Dareen Tatour, translated into English by Tariq al Haydar

- Written on:

November 2, 2015, First published here https://arablit.org/2016/09/01/a-poet-behind-bars-a-new-poem-from-dareen-tatour/

November 2, 2015, First published here https://arablit.org/2016/09/01/a-poet-behind-bars-a-new-poem-from-dareen-tatour/

Monday, 30 July 2018

Word of the day :- Gammon

Some would argue that the use of the word gammon politically is a rather mild one considering how those insulted by it view the world .It seems safe to say that someone who is referred to as gammon, would not be best pleased, and may find it very difficult to calm down due to an increase in their blood pressure.It should also be noted though that 'gammon' is not a racial slur, actually gammons come in all races and sexes, take Katie Hopkins for instance.

It is the latest in a long and (in)glorious line of political insults leading back to Aristphanes, to Nye Bevan that have sparked a thousand angry responses ever since. Annosh Chakelian of The News Stateman traced the first use of "gammon" back to Times columnist Caitlin Moran, who described former prime minister David Cameron as a "C-3PO made of ham" and a slightly camp gammon robot" Alas , this would not be the last time Mr Cameron would find his name unfavourably connected with a dead pig. One can also traced the coinage even further, noting that Charles Dickens employed it in the pages of Nicholas Nikleby (1839)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gammon_(insult)

All this name calling I guess can get rather childish though, think i'd best stick to being a snowflake, win my arguments in a more subtle way, otherwise I might find myself beating a hasty retreat from an impeding wall of gammon.

Saturday, 28 July 2018

Protect the Green-Haired Punk Turtle That Can Breathe Through Its Genitals!

The Mary River Turtle, an Australian reptile also known as the green-haired punk turtle , owing to the fact that many specimens are covered with growing strands of algae, that makes them look like they have a green mohawk, and also have two finger-like spikes to add to their overall 'punk rock' look.

This extraordinary creature is also able to stay underwater for up to three days thanks to its ability to breathe through gill-like organs in its genitals.Sadly it has recently been added to a list of the world's most vulnerable species by the Zoological Society of London. The turtle which can only be found in the Mary River in Queensland, was listed as the 30th most endangered reptiles by the ZSL's Edge of Existence programme, which uses a complex formula to award a threat score to unusual species at risk of exctinction.Many Edge reptiles are the sole survivors of ancient lineages whose branches of the Tree of Life stretch back to the age of dinosaurs. If we lose these species, there will be nothing like them left on Earth.

.https://www.edgeofexistence.org/

The Mary River Turtle is really one of the most fascinating reptile species on the planet and its dissapearance would be a huge loss.Though the turtle's total population is not known, its numbers began plummeting in the 1960's, when nest sites were pillaged and they were sold as pets, Advocates hope the new listing will help in the push for protection of its habitat. Punk may not be dead but this little fella is endangered, these special turtles now need our help to survive in their natural habitat. Please sign the following petition urging the Australian government to protect the Mary River Turtle now!

https://www.thepetitionsite.com/888/035/391/protect-the-green-haired-punk-turtle-that-can-breathe-through-its-genitals/?TAP=1732

Thursday, 26 July 2018

William Styron ( 11/6/25 - 1/11/06) - Darkness Visible (an extract)

A post from 11/12/11 updated.

William Styron, who first descended into clinical depression at the age of sixty, described himself as "one who had suffered from the malady in extremis, yet inspiringly returned to tell the tale about mans ability to endure in extreme circumstances, I personally am very grateful that he did. Styron was one of the lucky ones , thousands of us are still unfortunate to live with this condition from day to day, some of us sadly do not have the means to survive, and tell our stories.

Remember a lot of people with mental health problems never actually seek professional help. Sometimes when sought the help is not what is needed. Even though William Styron's book Darkness Visible helped demystify the subject,with his vivid account of his descent into clinical depression, there is still serious stigma attached.This book has helped me though, when I too have been suffering and would strongly recommend it. The complex wrestling of the human soul is often difficult to avoid, life for some of us can be overwhelming. Personally speaking when my melancholy calls ,it often arrives uninvited.

Attracts some like a magnet. But as seasons flow, new tactics emerge , sometimes they work, every small step is because you are living. Every day one of survival. It forces us to look, join the dots, life as one big balancing act. Find the means to veer away from the darkness within. Even though episodes can return, the waves can be broken, peaked and moved over.

Remember there is nothing to be ashamed off . Courage lies within all of us, beyond the confines of despair, as Styron reminds me, our greatest hope lies in the passage of time and " the passing of the storm.... Mysterious in its coming, mysterious in its going, the affliction runs its course, and one finds peace." After a bout recently, I am one of the lucky ones, have at least a few caring listening ears, I will continue to avoid the dodgems though, try and keep on surviving !

Remember a lot of people with mental health problems never actually seek professional help. Sometimes when sought the help is not what is needed. Even though William Styron's book Darkness Visible helped demystify the subject,with his vivid account of his descent into clinical depression, there is still serious stigma attached.This book has helped me though, when I too have been suffering and would strongly recommend it. The complex wrestling of the human soul is often difficult to avoid, life for some of us can be overwhelming. Personally speaking when my melancholy calls ,it often arrives uninvited.

Attracts some like a magnet. But as seasons flow, new tactics emerge , sometimes they work, every small step is because you are living. Every day one of survival. It forces us to look, join the dots, life as one big balancing act. Find the means to veer away from the darkness within. Even though episodes can return, the waves can be broken, peaked and moved over.

Remember there is nothing to be ashamed off . Courage lies within all of us, beyond the confines of despair, as Styron reminds me, our greatest hope lies in the passage of time and " the passing of the storm.... Mysterious in its coming, mysterious in its going, the affliction runs its course, and one finds peace." After a bout recently, I am one of the lucky ones, have at least a few caring listening ears, I will continue to avoid the dodgems though, try and keep on surviving !

Darkness Visible (an extract) - William Styron

' When I was first aware that I had been laid low by the disease, I felt a need, among other things, to register a strong protest against the word 'depression'. Depression, most people know, used to be termed 'melancholia', a word which appears in English as early as the year 1303 and crops up more than once in Chaucer, who in his usage seemed to be aware of its pathological nuances. ' Melancholia' would still appear to be a far more apt and evocative word for the blacker forms of the disorder, but it was usurped by a noun with a bland tonality and lacking any magisterial prescence, used indifferently to describe an economic decline or a rut in the ground, a true wimp of a word for such a major illness. It may be that the scientist generally held resposible for its currency in modern times, a Johns Hopkins Medical School faculty member justly venerated - the Swiss born psychiatrist Adolf Meyer - had a tin ear for the finer rhythyms of the English and therefore was unaware of the semantic damage he had inflicted by offering 'depression'' as a descriptive noun for such a terrible and raging disease. Nonetheless, for over seventy-five years the word has slithered innocuously through the language like a slug, leaving little trace of its intrinsic malevolence and preventing, by its very insipidity, a general awareness of the horrible intensity of the disease when out of control.

As one who has suffered from the malady in extremis yet returned to tell the tale, I would lobby for a truly arresting designation. 'Brainstorm', for instance, has unfortunately been preempted to describe, somewhat jocularly, intellectual inspiration. But something along these lines is needed. Told that someone's mood disorder has evolved into a storm - a veritable howling tempest in the brain, which is indeed what a clinical depression resembles like nothing else - even the uninformed layman might display sympathy rather than the standard reaction that ' depression' evokes, something akin to 'So what?' or 'You'll pull out of it' or 'We all have bad days.' The phrase 'nervous breakdown' seems to be on its way out, certainly deservedly so, owing to its insinuation of a vaque spinelessness, but we still seem destined to be saddled with 'depression' until a better, sturdier name is created.

The depression that engulfed me was not of the manic type- the one accompanied by euphoric highs - which would have most probably presented itself earlier in my life. I was sixty when the illness struck for the first time, in the 'unpilor' form, which leads straight down. I shall never learn what caused my depression, as no one will ever learn about their own. To be able to do so will likely for ever prove to be an impossibility,so able complex are the intingled factors of abnormal chemistry, behaviour and genetics. Plainly, multiple components are involved - perhaps three or four, most probably more, in fathomless permutations. That is why the greatest fallacy about suicide lies in the belief that there is a single immediate answer - or perhaps combined answers - as to why the deed was done.

The inevitable question 'Why did he (or she) do it? usually leads to odd speculations, for the most part fallacies themselves. Reasons were quickly advanced for Abbie Hoffman's death: his reaction to an auto accident he had suffered, the failure of his most recent book, his mother's serious illness. With Randall Jarrell it was a declining career cruelly epitomised by a vicious book review and his consequent anguish. Primo Levi, it was rumoured, had been burdened by caring for his paralytic mother, which was more onerous to his spirit than even his experience at Auschwitz. Any one of these factors may have lodged like a thorn in the sides of the three men, and been a torment. Such aggravations may be crucial and cannot be ignored. But most people quietly endure the equivelent of injuries, declining careers, nasty book reviews, family illnesses. A vast majority of the survivors of Auschwitz have borne up fairly well. Bloody and bowed by the outrages of life, most human beings still stagger on down the road, unscathed by real depression. To discover why some people plunge into the downward spiral of depression, one must search beyond the manifest crisis - and then still fail to come up with anything beyond wise conjecture.

The storm which swept me into a hospital in December began as a cloud no bigger than a wine goblet the previous June. And the cloud - the manifest crisis - involved alcohol, a substance I had been abusing for forty years. Like a great many American writers, whose sometime lethal addiction to alcohol has become so legendary as to provide in itself a stream of studies and books, I use alcohol as the magical conduit to fantasy and euphoria, and the the enhancement of the imagination. There is no need either to rue or apologise for my use of this soothing, often sublime agent, which had contributed greatly to my writing;although I never sat down a line while under its influence, I did use it - often in conjuntion with music - as a means to let my mind concieve visions that the unaltered, sober brain has no assess to. Alcohol was an invaluable senior partner of my intellect, besides being a friend whose manifestations I sought daily - sought also, I now see, as a means to calm the anxiety and incipient dread that I had hidden away for so long somewhere in the dungeons of my spirit.

The trouble was at the beginning of this paticular summer, that I was betrayed. It struck me quite suddenly, almost overnight; I could no longer drink. It was as if my body had risen up in protest, along with my mind, and had conspired to reject this daily mood bath which it had so long welcomed, and, who knows? perhaps even come to need. Many drinkers have experiencd this intolerance as they have grown older. I suspect that the crisis was atleast partly metabolic - the liver rebelling, as if to say, 'No more, no more' - but at any rate I discovered that alcohol in miniscule amounts, even a mothful of wine, caused me nausea, a desperate and unpleasant wooziness, a sinking sensation, and ultimately a distinct revulsion. The comforting friend had abandoned me not gradually and reluctantly as a true friend might do, but like a shot - and I was left high and certainly dry, and unhelmed.

Neither by will nor by choice had I become an absteiner; the situation was puzzling to me, but it was also traumatic, and I date the onset of my depressive mood from the begining of this deprivation. Logically, one would be overjoyed that the body had so summarily dismissed a substance that was undermining its health; it was as if my system had generated a form of Antabuse, which should have allowed me to happily go my way, satisfied that a trick of nature had shut me off from a harmful dependence. But, instead, I began to experience a vaquely troubling malaise, a sense of something having gone cockeyed in the domestic universe I'd done so long, so comfortably. While depression is by no means unknown when people stop drinking, it is usually on a scale that is not menacing. But it should be kept in mind how idiosyncratic the faces of depression can be.

It was not really alarming at first, since the change was subtle, but I did notice that my surroundings took on a different tone at certain times: the shadows of nightfall seemed more sombre, my mornings were less buoyant, walks in the woods became less zetful, and there was a moment during my working hours in the late afternoon when a kind of panic and anxiety overtook me, just for a few minutes, accompanied by a visceral queasiness - such a seizure was at least alarming, after all. As I set down these recollections, I realise that it should have been plain to me that I ws already in the grip of the beginning of a mood disorder, but I was ignorant of such a condition at the time.

When I reflected on the curious alteration of my consciousness - and I was baffled enough from time to time to do so - I assumed that it all had to do somehow with my enforced withdrawal from alcohol. And, of course, to a certain extent this was true. But it is my conviction now that alcohol played a perverse trick on me when we said farewell to each other: although, as everyone should know, it is a major depressent, it had never truly depressed me during my drinking career, acting instead as a shield against anxiety. Suddenly vanished, the great ally which for so long had kept my demons at bay was no longer there to prevent those demons from beginning to swarm through the subconscious, and I was emotionally naked, vulnerable as I had never been before. Doubtless depression had hovered near me for years, waiting to swoop down. Now I was in the first stage- premonitory, like a flicker of sheet lightning barely percieved depression's black tempest.

I was on Martha's Vineyard, where I've spent a good part of each year since the sixties, during that exceptionally beautiful summer. But I had begun to respond indifferenty to the islands pleasures. I felt a kind of numbness, a reservation, but more particularly odd fragility - as if my body had actually become frail, hypersensitive and somehow disjointed and clumsy, lacking normal coordination. And soon I was in the throes of a pervasive hypochondria. Nothing felt quite right with my corpereal self; there were twitches and pains, sometimes intermittent, often seemingly constant that seemed to presage all sorts of dire infirmities. (Given these signs, one can understand how, as far back as the seventeenth century - in the notes of contemporary physicians, and in the perceptions of John Dryden and others - a connection is made between melancholia and hypochondria; the worlds are often interchangeable, and were so used until the nineteenth century by writers as various as Walter Scott and the Brontes, who also linked melancholy to a preoccupation with bodily ills.) It is easy to see how this condition is part of the psyche's apparatus of defence: inwilling to accept its own gathering deterioration, the mind announces to its indwelling consciousness that it is the body with its perhaps correctable defects - not the precious and irreplaceable mind - that is going haywire.

In my case , the overall effect was immensely disturbing, augmenting the anxiety that was by now never quite absent from my waking hours and fuelling still another strange behaviour pattern - a fidgety restlessness that kept me on the move, somewhat to the perplexity of my family and friends. Once, in late summer, on an airplane trip to New York, I made the reckless mistake of downing a scotch and soda - my first alchol in months - which promptly sent me into a tailspin, causing me such a horrified sense of disease and interior doom that the very next day I rushed to a Manhattan intern, who inaugurated a long series of tests. Normally I would have been satisfied, indeed elated, when after three weeks of high-tech and extremely expensive evaluation, the doctor pronounced me totally fit; and I was happy, for a day or two, until there once gain began the rythmic daily erosion of my mood - anxiety, agitation, unfocused dread.

By now I had moved back to my house in Connecticut. It was October, and one of the unforgettable features of tihis stage of my disorder was the way in which my own farmhouse, my beloved home for thirty years, took on for me at that point when my spirits regularly sank to their nadir an almost palpable quality of ominousness. The fading evening light - akin to that famous 'slant of light' of Emily Dickinson's, which spoke to her of death, of chill extinction - had none of its familiar autumnal loveliness, but ensnared me in a suffocating gloom. I wondered how this friendly place teeming with such memories of (again in her words ) 'Lads and Girls', of laughter and ability and Sighing,/ And Frocks and Curls', could almost perceptively seem so hostile and forbidding. Physically, I ws not alone. As always Rose was present and listened with unflagging patience to my complaints. But I felt an immense and aching solitude. I could no longer concentrate during those afternoon hours, which for years had been my working time, and the act of writing itself, becomming more and more difficult and exhausting, stalled, then finally ceased.

William Styron's house in Connecticut.

There were also dreadful, pouncing seizures of anxiety. One bright day on a walk through the woods with my dog I heard a flock of Canada geese honking high above trees ablaze with foliage, ordinarily a sight and sound that would have exhilarated me, the flight of birds caused me to stop, riveted with fear, and I stood stranded there, helpless, shivering, aware for the first time that I had been stricken by no mere pangs of withdrawal but by a serious illness whose name and actuallity I was able to finally to acknowledge. Going home I couldn't rid my mind of the line of Baudelaire's, dredged up from the distant past, that for several days had been skittering around at the edge of my consciousness: 'I have felt the the wind of the wing of madness.'

Our perhaps understandable modern need to dull the sooth-tooth edges of so many of the afflicions we are heir to has led us to banish the harsh old fashioned words: madhouse, asylum, insanity, melancholia, lunatic, madness. But never let it be doubted that depression, in its extreme form, is madness. The madness results from an abherrrant biochemical process. It has been established with reasonable certainty ( after strong resistance from many psychiatrists, and not all that long ago) that such madness is chemically induced amid the neurotransmitters of the brain, probably as the result of systemic stress, which for unknown reasons cause a depletion of the chemicals norepinephrine and srontonin, and the increase of a hormone, cortsol. With all its upheaval in the brain tissues, the alternate drenching and deprivation, it is no wonder that the mind begins to feel aggrieved, stricke, and the muddied thought processes register the distress of an organ in convulsion. Sometimes, though not very often, such a disturbed mind will turn to violent thoughts regarding others. But with their minds turned agonizingly inward, people with depression are usually dangerous only to themselves. The madness of depression is, generally speaking, the antithesis of violence. It is a storm indeed. but a storm of murk. Soon evident are the slowed-down responses, near paralysis, psychic energy throttled back close to zero. Ultimately, the body is affected and feels sapped, drained.

That fall as the disorder gradually took full possession of my system, I began to concieve that my mind itself was like one of those outmoded small- town telephone exchanges, being gradually inudated by floodwaters: one by one, the normal circuits began to drown, causing some of the functions of the body and nearly all those pf instinct and intellect slowly to disconnect.

There is a well-known checklist of some of these functions and their failures. Mine conked out fairly close to schedule, many of them following the pattern of depressive seizures. I particularly remember the lamentable near dissapearance of my voice. It underwent a strange transformation, becomming at times quite faint, wheezy and spasmodic - a friend observed later that it was the voice of a ninety-year old. The libido also made an early exit, as it does in most major illnesses - it is the superfluous need of a body in beleagured emergency. Many people lose all appetite; mine was relatively normal, but I found myself eating only for substistence: food, like everything else within the scope of sensation, was utterly without saviour. Most distressing of all the instinctual disruptions was that of sleep, along with a complete absence of dreams.

Exhaustion combined with sleepnessness is a rare torture. The two or three hours of sleep I was able to get at night were always at the behest of the Haleion - a matter which deserves particular notice. For some time now many experts in psycho-pharnology have warned that the benzodiazpine family of tranquilliszers, of which Halcion is one (Valium and Ativan are others), is capable of depressing mood and even precipitating a major depression. Over two years before my siege, an insouciant doctor had prescribed Ativan as a bedtime aid, telling me airily that I could take it casually as apirin. The Physicians' Desk Reference, the pharmeacological bible, reveals that the medicine I had been ingesting was (a) three times the normally prescribed strength, (b) not advisable as a medication for more than a month or so, and (c) to beused with special caution by people of my age. At the time of which I am speaking I was no longer taking Ativian but had become addicted to Halcion and was consuming large doses. It seems reasonable to think that this was still another contributary factor to the trouble that had come upon me. Certainly , it should be a caution to others.

At any rate, my few hours of sleep were usually terminated at three or four in the morning, when I stared up into yawning darkness, wondering and waking at the devastation taking place in my mind, and awaiting the dawn, which usually permitted me a feverish, dreamless nap.I'm fairly certain that it was during one of these insomniac trances that there came over me the knowledge - a wierd and shocking revelation, like that of some long-beshrouded metaphysical truth - that this condition would cost me my life if it continued on such a course. This must have been just before my trip to Paris. Death, as I have said, was now a daily prescence, blowing over me in cold gusts. I had not concieve precisely how my end would come. In short, I had not concieved precisely how my end would come. In short, I ws still keeping the idea of suicide at bay. But plainly the possibility was around the corner, and I would soon meet it face to face.

What I had begun to discover is that, mysteriously and in ways that are totally remote from normal experience, the grey drizzle of horror induced by depression takes on the quality of physical pain. But it is not an immedately identifiable pain, like that of a broken limb. It may be more accurate to say that despair, owing to some evil trick played upon the sick brain by the inhabiting psyche, comes to resembe the diabolical discomfort of being imprisoned in a fiercely overheated room. And because no breeze stirs this cauldron, because there is no escape from this smothering confinement, it is entirely natural that the victim begins to think ceaselessly of oblivion.'

Reprinted from :-

Darkness Visible - William Styron ( Cape 1991).

.More on William Styron here.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Styron

' When I was first aware that I had been laid low by the disease, I felt a need, among other things, to register a strong protest against the word 'depression'. Depression, most people know, used to be termed 'melancholia', a word which appears in English as early as the year 1303 and crops up more than once in Chaucer, who in his usage seemed to be aware of its pathological nuances. ' Melancholia' would still appear to be a far more apt and evocative word for the blacker forms of the disorder, but it was usurped by a noun with a bland tonality and lacking any magisterial prescence, used indifferently to describe an economic decline or a rut in the ground, a true wimp of a word for such a major illness. It may be that the scientist generally held resposible for its currency in modern times, a Johns Hopkins Medical School faculty member justly venerated - the Swiss born psychiatrist Adolf Meyer - had a tin ear for the finer rhythyms of the English and therefore was unaware of the semantic damage he had inflicted by offering 'depression'' as a descriptive noun for such a terrible and raging disease. Nonetheless, for over seventy-five years the word has slithered innocuously through the language like a slug, leaving little trace of its intrinsic malevolence and preventing, by its very insipidity, a general awareness of the horrible intensity of the disease when out of control.

As one who has suffered from the malady in extremis yet returned to tell the tale, I would lobby for a truly arresting designation. 'Brainstorm', for instance, has unfortunately been preempted to describe, somewhat jocularly, intellectual inspiration. But something along these lines is needed. Told that someone's mood disorder has evolved into a storm - a veritable howling tempest in the brain, which is indeed what a clinical depression resembles like nothing else - even the uninformed layman might display sympathy rather than the standard reaction that ' depression' evokes, something akin to 'So what?' or 'You'll pull out of it' or 'We all have bad days.' The phrase 'nervous breakdown' seems to be on its way out, certainly deservedly so, owing to its insinuation of a vaque spinelessness, but we still seem destined to be saddled with 'depression' until a better, sturdier name is created.

The depression that engulfed me was not of the manic type- the one accompanied by euphoric highs - which would have most probably presented itself earlier in my life. I was sixty when the illness struck for the first time, in the 'unpilor' form, which leads straight down. I shall never learn what caused my depression, as no one will ever learn about their own. To be able to do so will likely for ever prove to be an impossibility,so able complex are the intingled factors of abnormal chemistry, behaviour and genetics. Plainly, multiple components are involved - perhaps three or four, most probably more, in fathomless permutations. That is why the greatest fallacy about suicide lies in the belief that there is a single immediate answer - or perhaps combined answers - as to why the deed was done.

The inevitable question 'Why did he (or she) do it? usually leads to odd speculations, for the most part fallacies themselves. Reasons were quickly advanced for Abbie Hoffman's death: his reaction to an auto accident he had suffered, the failure of his most recent book, his mother's serious illness. With Randall Jarrell it was a declining career cruelly epitomised by a vicious book review and his consequent anguish. Primo Levi, it was rumoured, had been burdened by caring for his paralytic mother, which was more onerous to his spirit than even his experience at Auschwitz. Any one of these factors may have lodged like a thorn in the sides of the three men, and been a torment. Such aggravations may be crucial and cannot be ignored. But most people quietly endure the equivelent of injuries, declining careers, nasty book reviews, family illnesses. A vast majority of the survivors of Auschwitz have borne up fairly well. Bloody and bowed by the outrages of life, most human beings still stagger on down the road, unscathed by real depression. To discover why some people plunge into the downward spiral of depression, one must search beyond the manifest crisis - and then still fail to come up with anything beyond wise conjecture.

The storm which swept me into a hospital in December began as a cloud no bigger than a wine goblet the previous June. And the cloud - the manifest crisis - involved alcohol, a substance I had been abusing for forty years. Like a great many American writers, whose sometime lethal addiction to alcohol has become so legendary as to provide in itself a stream of studies and books, I use alcohol as the magical conduit to fantasy and euphoria, and the the enhancement of the imagination. There is no need either to rue or apologise for my use of this soothing, often sublime agent, which had contributed greatly to my writing;although I never sat down a line while under its influence, I did use it - often in conjuntion with music - as a means to let my mind concieve visions that the unaltered, sober brain has no assess to. Alcohol was an invaluable senior partner of my intellect, besides being a friend whose manifestations I sought daily - sought also, I now see, as a means to calm the anxiety and incipient dread that I had hidden away for so long somewhere in the dungeons of my spirit.

The trouble was at the beginning of this paticular summer, that I was betrayed. It struck me quite suddenly, almost overnight; I could no longer drink. It was as if my body had risen up in protest, along with my mind, and had conspired to reject this daily mood bath which it had so long welcomed, and, who knows? perhaps even come to need. Many drinkers have experiencd this intolerance as they have grown older. I suspect that the crisis was atleast partly metabolic - the liver rebelling, as if to say, 'No more, no more' - but at any rate I discovered that alcohol in miniscule amounts, even a mothful of wine, caused me nausea, a desperate and unpleasant wooziness, a sinking sensation, and ultimately a distinct revulsion. The comforting friend had abandoned me not gradually and reluctantly as a true friend might do, but like a shot - and I was left high and certainly dry, and unhelmed.

Neither by will nor by choice had I become an absteiner; the situation was puzzling to me, but it was also traumatic, and I date the onset of my depressive mood from the begining of this deprivation. Logically, one would be overjoyed that the body had so summarily dismissed a substance that was undermining its health; it was as if my system had generated a form of Antabuse, which should have allowed me to happily go my way, satisfied that a trick of nature had shut me off from a harmful dependence. But, instead, I began to experience a vaquely troubling malaise, a sense of something having gone cockeyed in the domestic universe I'd done so long, so comfortably. While depression is by no means unknown when people stop drinking, it is usually on a scale that is not menacing. But it should be kept in mind how idiosyncratic the faces of depression can be.

It was not really alarming at first, since the change was subtle, but I did notice that my surroundings took on a different tone at certain times: the shadows of nightfall seemed more sombre, my mornings were less buoyant, walks in the woods became less zetful, and there was a moment during my working hours in the late afternoon when a kind of panic and anxiety overtook me, just for a few minutes, accompanied by a visceral queasiness - such a seizure was at least alarming, after all. As I set down these recollections, I realise that it should have been plain to me that I ws already in the grip of the beginning of a mood disorder, but I was ignorant of such a condition at the time.

When I reflected on the curious alteration of my consciousness - and I was baffled enough from time to time to do so - I assumed that it all had to do somehow with my enforced withdrawal from alcohol. And, of course, to a certain extent this was true. But it is my conviction now that alcohol played a perverse trick on me when we said farewell to each other: although, as everyone should know, it is a major depressent, it had never truly depressed me during my drinking career, acting instead as a shield against anxiety. Suddenly vanished, the great ally which for so long had kept my demons at bay was no longer there to prevent those demons from beginning to swarm through the subconscious, and I was emotionally naked, vulnerable as I had never been before. Doubtless depression had hovered near me for years, waiting to swoop down. Now I was in the first stage- premonitory, like a flicker of sheet lightning barely percieved depression's black tempest.

I was on Martha's Vineyard, where I've spent a good part of each year since the sixties, during that exceptionally beautiful summer. But I had begun to respond indifferenty to the islands pleasures. I felt a kind of numbness, a reservation, but more particularly odd fragility - as if my body had actually become frail, hypersensitive and somehow disjointed and clumsy, lacking normal coordination. And soon I was in the throes of a pervasive hypochondria. Nothing felt quite right with my corpereal self; there were twitches and pains, sometimes intermittent, often seemingly constant that seemed to presage all sorts of dire infirmities. (Given these signs, one can understand how, as far back as the seventeenth century - in the notes of contemporary physicians, and in the perceptions of John Dryden and others - a connection is made between melancholia and hypochondria; the worlds are often interchangeable, and were so used until the nineteenth century by writers as various as Walter Scott and the Brontes, who also linked melancholy to a preoccupation with bodily ills.) It is easy to see how this condition is part of the psyche's apparatus of defence: inwilling to accept its own gathering deterioration, the mind announces to its indwelling consciousness that it is the body with its perhaps correctable defects - not the precious and irreplaceable mind - that is going haywire.

In my case , the overall effect was immensely disturbing, augmenting the anxiety that was by now never quite absent from my waking hours and fuelling still another strange behaviour pattern - a fidgety restlessness that kept me on the move, somewhat to the perplexity of my family and friends. Once, in late summer, on an airplane trip to New York, I made the reckless mistake of downing a scotch and soda - my first alchol in months - which promptly sent me into a tailspin, causing me such a horrified sense of disease and interior doom that the very next day I rushed to a Manhattan intern, who inaugurated a long series of tests. Normally I would have been satisfied, indeed elated, when after three weeks of high-tech and extremely expensive evaluation, the doctor pronounced me totally fit; and I was happy, for a day or two, until there once gain began the rythmic daily erosion of my mood - anxiety, agitation, unfocused dread.

By now I had moved back to my house in Connecticut. It was October, and one of the unforgettable features of tihis stage of my disorder was the way in which my own farmhouse, my beloved home for thirty years, took on for me at that point when my spirits regularly sank to their nadir an almost palpable quality of ominousness. The fading evening light - akin to that famous 'slant of light' of Emily Dickinson's, which spoke to her of death, of chill extinction - had none of its familiar autumnal loveliness, but ensnared me in a suffocating gloom. I wondered how this friendly place teeming with such memories of (again in her words ) 'Lads and Girls', of laughter and ability and Sighing,/ And Frocks and Curls', could almost perceptively seem so hostile and forbidding. Physically, I ws not alone. As always Rose was present and listened with unflagging patience to my complaints. But I felt an immense and aching solitude. I could no longer concentrate during those afternoon hours, which for years had been my working time, and the act of writing itself, becomming more and more difficult and exhausting, stalled, then finally ceased.

William Styron's house in Connecticut.

Our perhaps understandable modern need to dull the sooth-tooth edges of so many of the afflicions we are heir to has led us to banish the harsh old fashioned words: madhouse, asylum, insanity, melancholia, lunatic, madness. But never let it be doubted that depression, in its extreme form, is madness. The madness results from an abherrrant biochemical process. It has been established with reasonable certainty ( after strong resistance from many psychiatrists, and not all that long ago) that such madness is chemically induced amid the neurotransmitters of the brain, probably as the result of systemic stress, which for unknown reasons cause a depletion of the chemicals norepinephrine and srontonin, and the increase of a hormone, cortsol. With all its upheaval in the brain tissues, the alternate drenching and deprivation, it is no wonder that the mind begins to feel aggrieved, stricke, and the muddied thought processes register the distress of an organ in convulsion. Sometimes, though not very often, such a disturbed mind will turn to violent thoughts regarding others. But with their minds turned agonizingly inward, people with depression are usually dangerous only to themselves. The madness of depression is, generally speaking, the antithesis of violence. It is a storm indeed. but a storm of murk. Soon evident are the slowed-down responses, near paralysis, psychic energy throttled back close to zero. Ultimately, the body is affected and feels sapped, drained.

That fall as the disorder gradually took full possession of my system, I began to concieve that my mind itself was like one of those outmoded small- town telephone exchanges, being gradually inudated by floodwaters: one by one, the normal circuits began to drown, causing some of the functions of the body and nearly all those pf instinct and intellect slowly to disconnect.

There is a well-known checklist of some of these functions and their failures. Mine conked out fairly close to schedule, many of them following the pattern of depressive seizures. I particularly remember the lamentable near dissapearance of my voice. It underwent a strange transformation, becomming at times quite faint, wheezy and spasmodic - a friend observed later that it was the voice of a ninety-year old. The libido also made an early exit, as it does in most major illnesses - it is the superfluous need of a body in beleagured emergency. Many people lose all appetite; mine was relatively normal, but I found myself eating only for substistence: food, like everything else within the scope of sensation, was utterly without saviour. Most distressing of all the instinctual disruptions was that of sleep, along with a complete absence of dreams.

Exhaustion combined with sleepnessness is a rare torture. The two or three hours of sleep I was able to get at night were always at the behest of the Haleion - a matter which deserves particular notice. For some time now many experts in psycho-pharnology have warned that the benzodiazpine family of tranquilliszers, of which Halcion is one (Valium and Ativan are others), is capable of depressing mood and even precipitating a major depression. Over two years before my siege, an insouciant doctor had prescribed Ativan as a bedtime aid, telling me airily that I could take it casually as apirin. The Physicians' Desk Reference, the pharmeacological bible, reveals that the medicine I had been ingesting was (a) three times the normally prescribed strength, (b) not advisable as a medication for more than a month or so, and (c) to beused with special caution by people of my age. At the time of which I am speaking I was no longer taking Ativian but had become addicted to Halcion and was consuming large doses. It seems reasonable to think that this was still another contributary factor to the trouble that had come upon me. Certainly , it should be a caution to others.

What I had begun to discover is that, mysteriously and in ways that are totally remote from normal experience, the grey drizzle of horror induced by depression takes on the quality of physical pain. But it is not an immedately identifiable pain, like that of a broken limb. It may be more accurate to say that despair, owing to some evil trick played upon the sick brain by the inhabiting psyche, comes to resembe the diabolical discomfort of being imprisoned in a fiercely overheated room. And because no breeze stirs this cauldron, because there is no escape from this smothering confinement, it is entirely natural that the victim begins to think ceaselessly of oblivion.'

Reprinted from :-

Darkness Visible - William Styron ( Cape 1991).

.More on William Styron here.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Styron

Sunday, 22 July 2018

Laboratories of existence

I follow earth's vibrations

Well remembered tones

Ancient paths and heartbeats

Memories of old friends

That continue to guide

Fill my vision with kindness,

As I float into the future

In laboratories of existence,

Following deep principles

Of love and devotion

Carrying hope and pride

Growing and evolving

In this little world of mine

The air smelling of freedom

Fanning dreams, creating sparks

Though heart often weighs heavily

Happiness never seems to die

Find lights to wade through the dark.

Saturday, 21 July 2018

As Gaza is bombed again, time to end the blockade

Israeli warplanes launched a large-scale attack across the Gaza Strip on Friday, partly over the flyng of kites, in one of the fiercest in years, unleashing the heaviest bombing assault on Gaza since the 2014 war, that killed more than 2,000 Palestinians.

The airstrikes began to slam Gaza just hours after Israeli soldiers gunned down at least three Palestinians during anti-occupation demonstrations. The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) says one of its soldiers was killed by retaliatory gunfire from the Palestinians.Successive explosions rocked Gaza City at nightfall and the streets emptied as warplanes struck dozens of sites. Defense Minister Avigdor Lieberman threatened to “carry out an operation that is of a much wider scope and much more painful than Operation Protective Edge” and this bombing is following through on those threats.

Israel’s Education Minister was reported insisting warplanes should drop bombs over the heads of Palestinian children flying the kites, even when the head of the army pushed back! This current military assault coming after months of successful organizing and actions by Gaza protesters and international support for the Great Return March. Palestinians have now been protesting at the border for 17 weeks,threatening to “return” to the lands their forefathers lost when Israel was created in 1948. Gaza health officials say more than 130 Palestinians have been killed and 15,000 injured by Israeli forces, during that time. Palestinians in Gaza see the flying off kites and balloons over the illegal border as legitimate resistance against Israel’s more than decade-long blockade.

At least four Palestinians were killed subsequently in Gaza on Friday, following the deaths of two teenagers, Amir and Luay, who were killed by Israeli arplanes earlier in the week while they were playing on a roof.

In response activists began circulating the #Stop theWar hashtag in an effort to pressure the international community to step in and stop Israel's efforts to launch yet another catastrophic assault on the occupied, blockaded, unlivable and exhausted open air prison that is the Gaza Strip which has seen ts people choking under 11 years of seige. Measuring 365 square kilometres and home to 2m people, (half of whom are children), one of the most crowded and miserable places on Earth. It is short of medicine, power and other essentials. The tap water is undrinkable; untreated sewage is pumped into the sea. Gaza already has one of the world’s highest jobless rates, at 44%, it's people being denied the necessities for means to live

In short, Palestinians, will justifiably continue to resist, feel much anger, and the international community has a duty to call Israel to account as it continues to unleash collective punihment on its people, as it carries out aggression with impunity, we must continue the call for the end of the illegal Gaza blockade as Israel’s occupation of the Palestinian territories carries on relentlessly because of the military, economic and political support it receives from governments around the world.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)