Guillaume Apollinaire was a French poet, playwright and art critic born in Italy on this day in 1890 to Angelica de Kostrowitzky who registered

the infant who would become France’s greatest war poet. as Guglielmo

Alberto Wladimiro Alessandro Apollinare

Angelica hailed from Lithuanian-Polish petty aristocracy. Her

grandfather had been wounded while fighting with the czar’s troops at

Sebastopol. Her father was a valet to the pope. Angelica was a demimondaine, kept by wealthy lovers.

Family legend claimed that Guillaume’s father was a

Roman aristocrat. But in the first decade of the 20th century, when

Apollinaire was a writer and art critic at the heart of the pre-war

cultural revolution in Paris, his friends believed him to be the

illegitimate son of a Roman prelate.

“He was registered as the son of an unknown father and remained so,”

says Laurence Campa, the author of the definitive biography of

Apollinaire, published by Gallimard in Paris.Officially, Apollinaire was a citizen of Russia

Angelica took Guillaume and his half- brother Albert to the Côte d’Azur,

where she haunted the gambling dens of Nice and Monaco.

In his youth Apollinaire assumed the

identity of a Russian prince. He received a French education at the

Collège Saint-Charles in Monaco, and afterwards in schools in Cannes and

Nice.

At the age of 20 he

traveled to Paris before traveling to Germany where he fell in love with

the countryside and wrote several poems. He also fell in love with an

English girl, whom he followed to London only to be rebuffed, which

caused him to write his poem, “Chanson du mal-aimé” (“Song of the Poorly

Loved”).

In to Paris he earned a reputation as a writer

and befriended many of the city’s struggling artists, many of whom went

on to some acclaim, including Alfred Jarry,

https://teifidancer-teifidancer.blogspot.com/2011/06/alfed-jarry-891877-11107-life-as-riot.html Andre Derain, Raoul Dufy and Maurice de

Vlaminck. He championed the work of the folk artist Henri Rousseau.

Apollinaire introduced the artists to African art, which was beginning

to become popular in France. His influence on the young artists of the

time is immeasurable. Through him the artists became Cubists, as an art critic

Apollinaire was the first to champion Cubist painting;he wrote

the preface to their catalogue, producing his own “

Peinture cubist”

(Cubist Painters) in 1913,which explored the theory

of cubism and analysed psychologically the chief cubists and their works.

According to Apollinaire, art is not a mirror held up to nature, so cubism

is basically conceptual rather than perceptual. By means of the mind,

one can know the essential transcendental reality that subsists 'beyond the

scope of nature.

The term Orphism (1912) is also his and described 'the art of painting new structures out of elements

that have not been borrowed from the visual sphere but have been created

entirely by the artist himself, and have been endowed by him with the

fullness of reality.' Among Orphicist artist were Robert Delaunay, Fernand

Léger, Francis Picabia, and Frantisek Kupka.. Apollinaire also wrote one of the earliest Surrealist literary works, the play The Breasts of Tiresias (1917), which became the basis for the 1947 opera Les mamelles de Tirésias.

Apollinaire’s writing on art was more than simple review. He captured

the spirit of the movements. Of Picasso, he wrote in the March issue of

Montjoie!, “He is a new man and the world is as he represents it. He has

enumerated its elements, its details, with a brutality that knows, on

occasion, how to be gracious.” Apollinaire, in 1918, wrote of Matisse,

“With the years, his art has perceptibly stripped itself of everything

that was non-essential; yet its ever-increasing simplicity has not

prevented it from becoming more and more sumptuous.”

While producing a large quantity of art criticism, he also found time to

publish a book of poetry, “The Rotting Magician” in 1909, a collection

of stories, “L’Hérésiarque et Cie” (“The Heresiarch and Co.”), in 1910, a

collection of quatrains called “Le Bestiaire” in 1911, and what is

considered his masterpiece, “Alcools,” The prose-poem depicted the entombment of

Merlin the Enchanter by his love. From his sufferings Merlin creates a

new world of poetry. Alcools combined classical verse forms

with modern imagery, involving transcriptions of street conversations

overheard by change and the absence of punctuation. It opened with the

poem Zone, in which the tormented poet wanders through streets after

the loss of his mistress. Among its other famous poems are 'Le pont

Mirabeau' and 'La chanson du mal-aime.'

“Alcools” is pronounced “al-coal,” meaning “spirits,” although it is

also an obvious pun on “alcohol.” Indeed, the original title was

“Brandy.”

Apollinaire was caught up, along with Picasso, in the theft of the “Mona

Lisa” from the Louvre in 1911, an incident that would indirectly lead

to his death. His reputation as a radical and as a foreigner, led to his

being arrested in August 1911, on suspicion of stealing the painting

and a number of Egyptian antiquities, although he was released five days

later for lack of evidence. The Egyptian sculptures had been taken by

Apollinaire’s former secretary Honoré Joseph Géry Pieret. In order to

protect himself, as he was also considered a suspicious foreigner,

Picasso publicly denied that he and Apollinaire were friends, causing a

rift in the friendship.In 1911.

Apollinaire had a rebellious spirit and seemed an unlikely solider,

but in December 1914 he voluntarily joined the French army, much to the

surprise of many of his friends, and was posted to the front in April

1915.While in military training, Apollinaire met Louise de Châtillon-Coligny, for whom he wrote many of his best war poems:

If I died over there on the army front

You would cry for a day oh Lou my beloved

And then my memory would fade as dies

A shell bursting on the army front

A beautiful shell like flowering mimosa

Apollinaire loved military life. He loved his training in arms and

horseback riding, and learning to use and care for the famous French 75

cannon. He loved the camaraderie of barracks life, and the infinite

number of new sights and sounds and experiences that the war brought.

“Soldiering is my true profession,” he wrote his Parisian friends. To

another he wrote, from training camp, “I love art so much, I have joined

the artillery.”

But as his biographer Campa points out, Apollinaire had not yet seen any

shells exploding. He would continue to use childlike imagery, and to

preserve an inner world of beauty, even in the trenches. But

Apollinaire’s experience of war also changed his poetry. In Bleuet (the equivalent of the poppy in Britain), Apollinaire described the psychological ravages of battle:

Young man

of the age of twenty

who has seen such terrible things . . .

.looked death in the face more

than a hundred times and you don’t

know what life is...

Apollinaire realised quickly that his “beloved Lou” was playing with

him. He continued to write to her, but also began a correspondence with

Madeleine Pagès, a literature teacher whom he met on a train in January

1915.

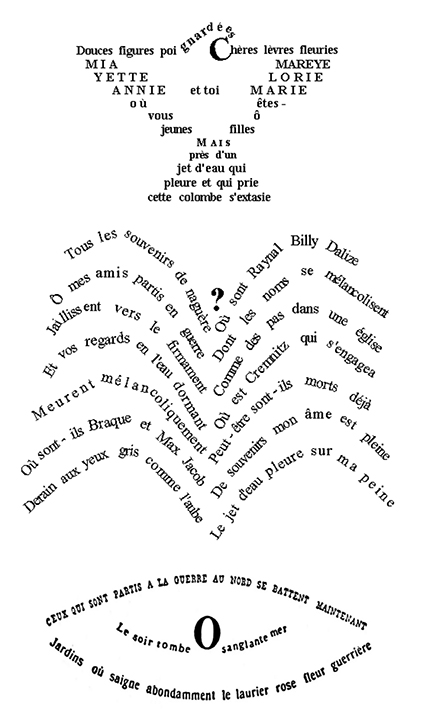

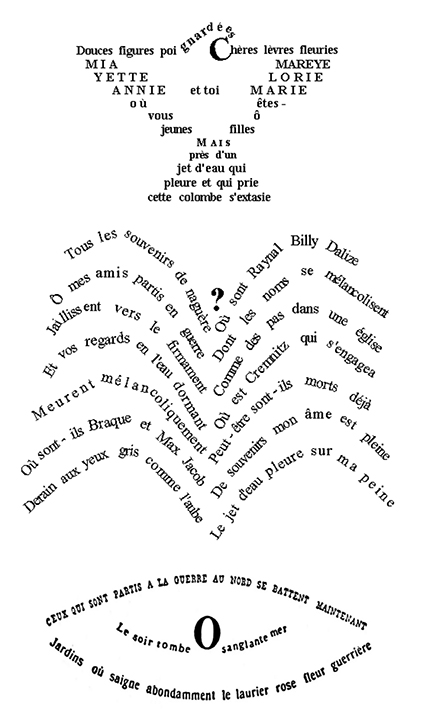

In 1918, Apollinaire published “Calligrammes: Poems of Peace and War

1913-1916,” a collection that was both visual and verbal. Calligrams are

poems where the arrangement of the words on the page adds meaning to

the text. In a letter to André Billy, Apollinaire writes,

“The Calligrammes are an idealisation of free verse poetry and

typographical precision in an era when typography is reaching a

brilliant end to its career, at the dawn of the new means of

reproduction that are the cinema and the phonograph.”

Apollinaire arranged

words on the page to form patterns resembling objects: a drunken man, a

watch, the Eiffel Tower. At the time this eccentric use of typography

was thought to have stretched poetry to its limit.

His other works include the novella "The Poet

Assassinated" (1916) and the play "The Breasts of Tiresias" (1917). The

latter was made into an opera (1947) by composer Francis Poulenc, who

also set many of Apollinaire's poems to music.

Letters to Madeleine

combine the three strains of Apollinaire’s poetry: sex, love and war.

His eroticism is often humorous and ironic, as when he writes of

midwives fantasising about priapic cannons. Some of it is so explicit

that one is amazed it passed the military censors: “My tense flesh,

hardened by desire will penetrate your flesh,” he wrote to Madeleine on

October 22nd, 1915.

Apollinaire’s letters are equally explicit about the war. In July 1915

he wrote of “the horrible horror of millions of big, blue flies,” of

“holes so filthy you want to vomit.” Four months later, it was “mud,

what mud, you cannot imagine the mud you have to have seen it here,

sometimes the consistency of putty, sometimes liked whipped cream or

even wax and extraordinarily slippery.”

In December, Apollinaire told Madeleine that “the heart jumps with

every thunder” of the Germans’ 105mm.

While in hospital, Apollinaire gave an interview to a

cultural magazine in which, with his usual prescience, he predicted

that cinema would soon become the most popular form of art.

In November 1915, Apollinaire was transferred at his request to the

96th Infantry Regiment and was promoted to 2nd lieutenant. It was a

matter of “virile pride,” writes Campa. Living conditions were better

for officers, and “something in him wanted to go to the limit of his

commitment. He believed that being a poet meant taking risks.”

He suffered a serious head injury in March 1916,

which required him being trepanned. He never really recovered from the wound.

Picasso portrayed the convalescent soldier with his head in bandages

and the medal of the Legion of Honour pinned to his chest.

Apollinaire;s epistolary engagement to Madeleine had faded

after he visited her on Christmas leave in 1915.

In his last letter to Madeleine , in September 1916, he wrote: “Almost all my

friends from the war are dead. I don’t dare write to the colonel to ask

him the details. I heard he himself was wounded.”

Apollinaire remained in Paris, still in uniform, as a military censor.

He was afraid of being sent back to the front, and the job allowed him

to frequent publishing circles. Campa, who studied his work in French

archives, says he was a lenient censor.

In May 1918, Apollinaire married Jacqueline Kolb, “the pretty redhead” for whom he wrote the last poem in Calligrammes.

Kolb’s lover had been killed on the same battlefield where Apollinaire

was wounded. Picasso and the art dealer Ambroise Vollard were witnesses

to the marriage.

Six months later, on November 9th, Apollinaire was killed by the

Spanish flu epidemic that claimed more lives than the entire war itself.

He was 38 years old, and the French language was deprived of untold

riches.

Apollinaire died on the day Kaiser Wilhelm abdicated. Legend has it

that from his top floor apartment at 202 Boulevard St Germain he heard

people shouting “À bas Guillaume!” In his delirium, the poet believed

they referred to him.artillery. “It jumps not from fear

or emotion – those things no longer exist after 15 months of war – but

it jumps because the change in air pressure shakes everything.”

In November 1915, Apollinaire was transferred at his request to the

96th Infantry Regiment and was promoted to 2nd lieutenant. It was a

matter of “virile pride,” writes Campa. Living conditions were better

for officers, and “something in him wanted to go to the limit of his

commitment. He believed that being a poet meant taking risks.”

Although he continued to write and promote the avant-garde on his

return to Paris, coining the term “Surrealism” in the program notes for

the ballet “ Cemetary,” created by Picasso, Erik Satie, Sergie Diaghilev

and Jean Cocteau.

Weakened by his war wound,

Apollianaire succumbed to Spanish Flu on Nov. 9, 1918, at the age of 38 and the French language was deprived of untold

riches He is buried in Pere Lachaise Cemetarym in Paris. By the time of his death, his reputation was secure as one of the great

French poets and art critics.

Apollinaire's stature has continued to grow

since his death, as the precursor of surrealism and as a modernist his influence on modern art is incredible. He inspired, cajoled,

encouraged and supported many of the early 20th century’s most

influential artists through his writings, as well as being a poet that

captured the zeitgeist of the period. There has rarely, if ever, been

a single man who has been the central of so many artistic spokes.

“Through his innovation and inventiveness, Apollinaire initiated

20th-century poetry,” says Campa. “By embracing cubism and abstraction,

he also opened the artistic century . . . Now he’s become a symbol of

the more than 500 French writers who perished in the first World War,

whose names are engraved on the walls of the Pantheon. He also

symbolises the many foreigners who sacrificed their lives for France.”

The following poem “The Stunned Dove and the Water Jet.” is a translation, rearranged conventionally, by Charles Bernstein. Its image features a bleeding dove

with spread wings, followed by a fountain with the water coming out of a

vase that is reminiscent of the dove’s wings.

Sweet stabbed faces dear floral lips

Mya Mareye

Yette and Lorie

Annie and you Marie

Where are you, oh young girls

But near a crying jet of water and praying

This dove is ecstatic

All the memories of yesteryear

O my friends gone to war

Well up to the firmament

And your eyes in the sleeping water

Die melancholy

Where are they Braque and Max Jacob

Derain with gray eyes like dawn

Where are Raynal Billy Dalize

Whose names are melancholisent

Like steps in a church

Where is Cremnitz who engaged

Maybe they are already dead

From memories my soul is full

The stream of water cries over my pain.

Those who went to the war

in the North are now fighting

The evening falls O bloody sea

Gardens where bleed abundantly

laurel rose flower warrior.