Self-Portrait with Cigarette, 1880

Henri-Edmond Cross French master neo-Impressionist painter, printmaker and anarchist was born Henri-Edmond-Joseph Delacroix in Douai, a commune in the Nord département in northern France on 20th of May 1856. He had no surviving siblings. His parents were French adventurer Alcide Delacroix and an English mother Fanny Woollett.

In order to distinguish himself from the painter Eugène Delacroix, Henri changed his name in 1881, shortening and Anglicizing his birth name to "Henri Cross".

In 1865 the family moved near Lille, a northern French city close to the Belgian border. Alcide's cousin, Dr. Auguste Soins, recognized Henri's artistic talent and was very supportive of his artistic inclinations, even financing the boy's first drawing instructions under painter Carolus-Duran the following year. Henri was Duran's protégé for a year. His studies continued for a short time in Paris in 1875 with François Bonvin before returning to Lille. He studied at the École des Beaux-Arts and in 1878, he enrolled at the Écoles Académiques de Dessin et d'Architecture, studying for three years in the studio of Alphonse Colas. His art education continued, under fellow Douai artist Émile Dupont-Zipcy, after moving to Paris in 1881.

Henri Edmond Cross regularly exhibited at the Paris Salon. Cross' early work was characterised by his use of dark, heavy colours, which became brighter under Claude Monet and Georges Seurat's influence.

In 1884, he founded the "Salon des Indépendants" together with Paul Signac and George Seurat and which consisted of artists displeased with the practices of the official Salon, and presented unjuried exhibitions without prizes.There he met and became friends with many artists involved in the Neo-Impressionist movement, including Georges Seurat, Albert Dubois-Pillet, and Charles Angrand.

Despite his association with the Neo-Impressionists, Cross did not adopt their style for many years. His work continued to manifest influences such as Jules Bastien-Lepage and Édouard Manet, as well as the Impressionists.The change from his early, somber, Realist work was gradual. His color palette became lighter and he worked en plein air, he painted in the brighter colors of Impressionism. In the latter part of the 1880s, he painted pure landscapes which showed the influence of Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro.

In about 1886, attempting again to differentiate himself from another French artist – this time, Henri Cros – he again changed his name, finally adopting "Henri-Edmond Cross". .

Around 1890, Henri-Edmond Cross' painting became discernible because of his unique use of the Neo-impressionist Pointillist style. The artist's landscapes, nudes and portraits were characterised by generous brush strokes and bright, clear colours.

In 1892 Cross's friend Paul Signac moved to nearby Saint-Tropez, where they frequently hosted gatherings in Cross's garden, attended by such luminaries as Henri Matisse, André Derain, and Albert Marquet.

Cross's affinity with the Neo-Impressionist movement extended beyond the painting style to include their political philosophies. Like Signac, Pissarro, and other Neo-Impressionists that Cross exhibited with Luce, Petitjean, La Rochefoucauld, Van Rysselberghe, Signac, Angrand, Seurat and the two sons of Pissarro, Cross believed in anarchist principles, with hope for a utopian society and subscribed to the ideas of the anarchist theorist Kropotkin.

Politics were actually inherent in the neoimpressionism movement. It was born during an especially turbulent period of French history, when industrial capitalism was overhauling the nation’s economy and cultural geography. Anarchism seemed to present a compelling salve for the rampant upheavals.

A variant termed anarcho-communism was formulated between the 1870s and 1890s by thinkers including Jean Grave, Pierre Kropotkin, Elisée Reclus, and Félix Fénéon, who advocated a combination of individual freedom and collective ownership of the means of production. They also provided ideological and material support for the neoimpressionists; Fénéon even gave the group their name.They believed that science and technology would help liberate humanity both materially and spiritually.

Cross painted landscapes where human figures blend with nature in harmony and evoked a future anarchist utopia in his paintings. Life was becoming gradually more controlled and regimented in the late 1800s with more obligations, more restrictions and an increasing complexity. All of these factors worked against creativity and spirituality and Cross and his fellow painters, writers and poets wanted to return to a world in which there was less control – a more utopian society. As he said "I want to paint happiness, the happy beings who will become the people in a few centuries when the purest anarchy is realised."

Signac had already painted a vast canvas depicting this future society first entitled Au Temps d’Anarchie (In The Time of Anarchy) and then Au temps D’Harmonie ( In the Time of Harmony) . Carefree work for the good of the community, free love, and the joys of doing nothing are depicted.

Au Temps d’Anarchie (In The Time of Anarchy) - Paul Signac

Cross undertook a similar painting with his L’Air du Soir (The Evening Air) in 1894.

L’Air du Soir (The Evening Air) - Henri-Edmond Cross

Evening Air depicts three sets of women languidly enjoying themselves beneath a group of trees set within an idyllic coastal landscape, while the dreamlike imagery and subtly applied chromatic scale the artist employs produces an overall mood of tranquillity.

Like the other painters mentioned above, Cross contributed to the anarchist movement by donating illustrations to the anarchist paper

Les Temps Nouveaux (

New Times) edited by Jean Grave.In 1896 Cross created a lithograph,

L'Errant (The Wanderer). This marked the first time he had worked with a publisher, and the piece was featured anonymously in

Les Temps Nouveaux. The protagonist has a vision where workers throw a flag, a crown, and probably other insignia of capitalism/authority into a bonfire:

https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/allan-antliff-anarchy-neo-impressionism-and-utopiaHere is a lithograph of L’errant at the Philadelphia Museum of Art:

Cross's anarchist sentiments influenced his choice of subjects: he painted scenes illustrating an idealistic world free of constraints and artificial rules, morals and formality, a world he longed for. He provided the cover illustration for the pamphlet À Mon Frère le Paysan (To My Brother The Peasant) written by the anarchist theorist and activist Élisée Reclus in 1899. The following year he did the same for Jean Grave’s booklet Enseignement Bourgeois et Enseignement Libertaire ( Bourgeois Education and Libertarian Education).

He provided an illustration for the book of lithographs published by Les temps Nouveaux in 1905 and a drawing for the book Patriotisme, Colonisation. However, he was conflicted by the need to provide propagandist illustrations and his reservations about compromising his artistic ideas, feeling constrained by the nature of the pieces he offered. This did not stop him on several occasions donating his works as prizes in fund raising lotteries for Les Temps Nouveaux.

The depiction in his early paintings of peasants co-existing in sparse and unspoiled rural settings devoid of urban trappings reflects a sentimental anarchist vision of life in the countryside where people live together in harmony away from the corruption of the city. These themes continued in his subsequent Neo-Impressionist paintings with his use of colorful decorative forms and classical motifs, encouraging the viewer to identify such poetic beauty with an idyllic anarchist society.

Cross's paintings are full of nude women in the open air - a sort of return to Dionysian bliss. His paintings are very beautiful. He was great atcapturing light and his paintings give the impression of someone who is constantly experiencing pure or enhanced perception. He tried to capture the shimmering beauty that accompanies this form of experience by using dots of colour (called Divisionist painting in academia)

The Flight of the Nymphs - Henri-Edmond Cross

Bathers - Henri-Edmond Cross

Pines Along the Shore - Henri-Edmond Cross

In Pines Along the Shore, painted in the south of France overlooking the Mediterranean, Cross weaves and layers separate brushstrokes, building his paint surface in a tapestry-like fashion from cool tones on the pine grove floor to brilliant foliage at the water’s edge to softer hues in the sky and mountains beyond.

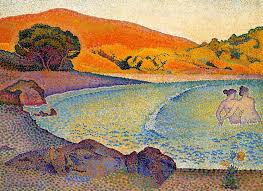

Two Women by the Shore - Henri-Edmond Cross

Cross’s attention to trees—along with other flora, the sea, and the sky, would have been consistent with anarchist thought. French anarchists even believed that the Mediterranean coast was an ideal cradle for the anarchist society of the future, because the sunshine and the harmoniously balanced elements (geographic and meteorological) were models of well-being for individuals and society.

Cross’s many paintings, drawings, and letters further attest to the importance of trees and flowers in his personal vision of happiness. He thoughtfully depicted specific species of plants throughout his career. In praising his Provençal environs, he described mimosas, eucalyptus, almond blossoms, and “hills covered in pines and cork-oaks that gently die away into the sea.”

Cross's paintings of the early- to mid-1890s are painted using closely and regularly positioned dots of colour [academia has invented a name for this too - Pointillism], but as his technique matured he saw that the same effects he wanted could be achieved using little squares of colour, blocks created using a broadish brush, with small areas of unpainted canvas [or canvas that had only been primed] to create the vibrant shimmering light filled effect he wanted.

At the time he painted there were a number of theories of colour being proposed both in science and in the artistic world and Cross appears to have known about them, as he is adept at using colour contrasts and colour complements. Cross stated that he was "far more interested in creating harmonies of pure colour, than in harmonizing the colours of a particular landscape or natural scene." If we put this another way, realism was never intended, the intention was to produce an impression of what he had seen.

Around 1896, as seen in this view of a spectacular cloud, he shifted toward larger, more emphatic brushstrokes, often surrounded by areas of white to achieve greater color intensity.

His method involved capturing the essence of the scene using watercolour or coloured pencil images in his sketchbooks and then using these notes back in the studio. He wrote of a rustic French outing: "Oh! What I saw in a split second while riding my bike tonight! I just had to jot down these fleeting things ... a rapid notation in watercolour and pencil: an informal daubing of contrasting colours, tones, and hues, all packed with information to make a lovely watercolour the next day in the quiet leisure of the studio."

The change from his early, sombre, Realist work was gradual. His colour palette became lighter and he started to paint outside. In 1891, Cross exhibited his first large piece using the technique he had evolved. The painting was a portrait of Madame Hector France, née Irma Clare, whom Cross had met in 1888. Robert Rosenblum wrote that "the picture is softly charged with a granular, atmospheric glow". Cross eventually married Madame France in 1893.

Madame Hector France - Henri-Edmond Cross

So love was clearly one driver to his work. But there are other influences. He smoked, and he smoked a lot, until eventually from a combination of smoke and the lead in paints he started to suffer from rheumatism.Cross had also began to experience troubles with his eyes in the early 1880s, and these grew more severe in the 1900s. He moved to the South of France in 1891 in an attempt to both help his rheumatism and capture the beautiful light there.

He settled in the small hamlet of Saint-Clair near Lavandou, and spent the remainder of his life there, leaving only for Italian trips in 1903 and 1908, and for his annual Indépendants exhibits in Paris. The Mediterranean landscape of the Côte d’Azur was to become his preferred subject matter for the remainder of his career, although he also painted idyllic scenes of bathers and mythological figures.

Although he suffered greatly from rheumatism and conjunctivitis between 1903 and 1910, this did not prevent him from producing finished work.

The Golden Isles - Henri-Edmond Cross

In 1904, Matisse - soon to become the leader of the new Fauvism style - sojourned in Saint-Tropez, frequenting Signac and taking an interest in Cross's experiments. The exchanges between the two artists were rich and their influence mutual.

The Fauvist painters (Wild Beasts).Charles Camoin, Henri Manguin, Albert Marquet, and Louis Valtat now also came down to the South of France. The revelling in colour that Cross saw in their paintings inspired him to be even more expressive in his own.

His daring use of pure, abstract color and decorative design significantly influenced Henri Matisse and the French Fauves . Among the other artists influenced by Cross's sensuous works were , André Derain, Wassilly Kandinksy, Henri Manguin and Jean Puy.

In 1905 he had a solo show at Galerie Eugene Druet featuring thirty paintings and thirty watercolors. The show was very successful, receiving critical acclaim, and most of the works were sold. Belgian Symbolist poet Emile Verhaeren, wrote: "These landscapes ... are not merely pages of sheer beauty, but motifs embodying a lyrical sense of emotion. Their rich harmonies are satisfying to the painter’s eye, and their sumptuous, luxuriant vision is a poet's delight. Yet this abundance never tips into excess. Everything is light and charming ..." .

His work was becoming more lyrical, and more decorative too. Cross had a model come to Saint-Clair and started to include a female figure in his sun-drenched landscapes, occasionally with a mythological pretext. Moving away from realistic themes, these paintings evince a new sensuous pleasure in painting. The catalogue to his last exhibition, organised in 1907 at the Bernheim-Jeune Gallery, was prefaced by Maurice Denis (1870-1943) and organized by his friend Felix Féneon, which included thirty-eight paintings and fifty-one watercolours.

In spite of his physical weakness, in 1908 Cross returned to Italy, this time to Tuscany and Umbria, where he delighted in the masterpieces in the museums of Florence, Pisa, Siena and Orvieto. In 1909, Cross was treated in a Paris hospital for cancer. In January 1910 he returned to Saint-Clair, where he died of the cancer just four days short of his 54th birthday on 16 May 1910. He rests in the cemetery at Lavandou, beneath the sun that was such an inspiration to him. His fellow anarchist painter Van Rysselberghe provided a medallion for his tomb.

Cross's body of work is relatively small and unlike Signac, whose children promoted and preserved his works, Cross had no such help as he had no descendents and after his death his paintings were scattered but today Cross's works can be found in various museums and public art galleries, including the Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Ohio; the Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Finnish National Gallery, Helsinki, Finland; the State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia; the Kunstmuseum Basel, Switzerland; the Museum of modern art André Malraux, Le Havre, France; the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, Cologne, Germany, etc.

As one scholar has written of Cross, ‘By the time of his death, his work stood as a hymn to color and sunlight, and helped form the vision of the Mediterranean coast which is commonplace today.’.