Blair Peach died from a broken skull on the 23rd of April 1979, as a result of being struck on the head by a truncheon wielding policeman from the Special Patrol Group during a demonstration outside Southall Town Hall, people will march in his honour in London, near a

primary school that's named after him. A plaque will also be unveiled in memory of him and Gurdeep Singh Chaggar, a local man who was killed by a racist gang in 1976.

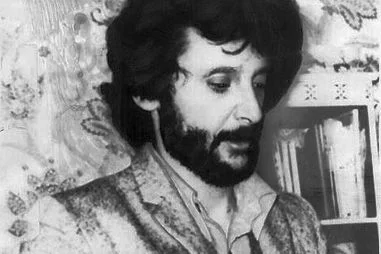

Clement Blair Peach was born in New Zealand on the 25th of March

1946. He studied at Victoria University of Wellington and

was for a time co-editor of the Argot literary magazine with his flatmates

Dennis List and David Rutherford. He worked as a fireman and as a hospital

orderly in New Zealand before moving to London in 1969 and started working as a teacher at the Phoenix School in Bow, Towe Hamlets, East London, a special needs

school.Peach was no stranger to radicalism and protest; he was a member of the Socialist Worker’s Party, as well as the Socialist Teacher’s Association and the East London Teacher’s Association, both within the National Union of Teachers. A committed anti-fascist.In 1974 he was acquitted of a charge of threatening behaviour after he challenged a publican who was refusing to serve black customers. He was also involved in campaigns against far-right and neo-Nazi groups; he was well known for leading a successful campaign to close a National Front building in the middle of the Bangladeshi community around Brick Lane. He was also arrested in April 1978, outside a public meeting held by the NF in an East London school. The police had arrested a fellow demonstrator, who was black and female. Peach instinctively placed himself between the woman and the arresting officer and said, “Leave her alone, she has not done anything.” He was arrested, and pleaded not guilty but was convicted, receiving a fine of £50.

Peach was elected President of the East London Teachers Association in 1978. Twice that year he was attacked by supporters of the National Front as he cycled home from teaching at the Phoenix School, and he suffered black eyes, bruising and cuts. According to the East Ender newspaper, “Doctors fear permanent damage may have been done to one of his eyes. His finger has been bitten through to the bone shredding the nerves.” Even before 23 April 1979, Peach was putting his body on the line in the cause of the struggle against fascism.

On St. George’s Day 1979, the fascist National Front held a meeting in Southall Town Hall. The Front had almost no supporters in the area, but was hoping to gain publicity by bulldozing its way through the Asian districts of outer London. The Anti-Nazi League held a counter demonstration outside the Town Hall. Peach was one of 3000 people to attend. The demonstration turned violent; over 150 people were injured, and 345 arrests were made.

Peach sustained a blow to the head from a weapon by a police officer at the junction of Beachcroft Avenue and Orchard Avenue, as he tried to get away from the demonstration. that left him staggering in to a nearby house. The impression is sometimes given that Blair Peach died instantly in the street but in fact he was still conscious though very dazed and finding it hard to speak when the ambulance arrived a quarter of an hour after the injury. There was no blood or external trauma but it’s clear that he was suffering from a swelling in the brain, what’s termed an extra-dural haematoma. Blair Peach died in an operating theatre at the New Ealing District Hospital at 12.10am. He was only 33 years old. At least three other anti fascist protesters were hit so hard to the head that their skulls were fractured.

Peach’s death struck a chord amongst the communities he had stood up for, and across the city as a whole. A few days after his death, 10000 people marched past the spot where he was fatally injured. His funeral was delayed by several months, until the 13th of June, but that was also attended by 10000 people. The night before his funeral, 8000 Sikhs went to see his body at the Dominion Theatre in Southall.

In the aftermath of Peach's murder, protesters were everywhere, flyposting, speaking, organising, discussing the lessons. The police were around, in very large numbers, but they did not dare to stop people from organising. It was almost as if the police were shamed by the enormity of what they had done. June 1979 also saw a 2,000-strong first Black people’s march against state harassment through central London.

Police investigated themselves in the aftermath of Blair Peach's death and identified 6 cops, 1 of whom administered the fatal blow. No one has ever been charged..

The death of Blair Peach was the dire outcome of a double-edged state racism. The police that day staunchly protected a racist gathering in a predominantly Asian community, while unleashing militarised measures of control and punishment on demonstrators looking to oppose the fascists (Institute of Race Relations, 1979).http://www.irr.org.uk/

Blair Peach’s death became a focal point for those who questioned the nature of the Special Patrol Group and the general lack of police accountability which that force epitomised. And, from the agitation of Blair’s family, especially his long term partner Celia Stubbs, about the inadequacy of the inquest system and the secrecy surrounding the coroner’s court and the evidence withheld from the family, was created the organisation INQUEST.

The Metropolitan Police commissioned an internal inquiry into what happened, which was led by Commander John Cass. 11 witnesses saw Peach struck by a member of the Special Patrol Group (SPG). The SPG was a centrally-based mobile group of officers focused on combating serious public disorder and crime that local divisions were unable to cope with. It started in 1961, and was replaces in 1987 by the Territorial Support Group, which also has a less-than stellar reputation amongst activists.

The pathologist’s report concluded that Peach was not hit with a standard issue baton, but an unauthorised weapon like a weighted rubber cosh,or a hosepipe filled with lead shot. When Cass’ team investigated the headquarters of the SPG, they found multiple illegal weapons including truncheons, knives, a crowbar, and a whip. 2 SPG officers had altered their appearance by growing or cutting facial hair since the protest, 1 refused to take part in an identity parade, and another was discovered to be a Nazi sympathiser. All of the officers’ uniforms were dry-cleaned before they were presented for examination.

Cass concluded that one of 6 officers had killed Peach, but he couldn’t be sure who exactly, because the officers had colluded to cover up the truth. He recommended that 3 officers be charged with perverting the course of justice, but no action was ever taken. The results of the inquiry were not published, and the coroner at the inquest into Peach’s death refused to allow it to be used as evidence, despite making use of it himself. Two newspapers, the Sunday Times and the Leveller, published leaks naming the officers that had travelled in the van that held Peach’s killer. They were Police Constables Murray, White, Lake, Freestone, Scottow and Richardson. When the lockers of their unit were searched in June 1979, one officer Greville Bint was discovered to have in his lockers Nazi regalia, bayonets and leather covered sticks. Another constable Raymond White attempted to hide a cosh. The failure of the authorities to adeguately invstigate Peach's murder left a huge feeling of resentment. Celia Stubbs, said: "This report totally vindicates what we have always believed - that Blair was killed by one of six officers from Unit 1 of the Special Patrol Group whose names have been in the public domain over all these years."

An annual award has since been presented by the UK's National Education Union to teachers to carry on Blair Peach's memory and after his death a number of writers have dedicated poems to his memory, including Chris Searle, Michael Rosen and Susannah Steele, Louis Johnson, Edward Bond, Sigi Moos, Sean Hutton and Tony Dickens, and songs including the following by dub poet Linton Kwesi Johnson in Jamaican patois.

Everywhere you go its the talk of the day,

Everywhere you go you hear people say,

That the Special Patrol them are murderers (murderers),

We cant make them get no furtherer,

The SPG them are murderers (murderers),

We cant make them get no furtherer,

Cos they killed Blair Peach the teacher,

Them killed Blair Peach, the dirty bleeders.

Blair Peach was an ordinary man,

Blair Peach he took a simple stand,

Against the fascists and their wicked plans,

So them beat him till him life was done.

Everywhere you go its the talk of the day,

Everywhere you go you hear people say,

That the Special Patrol them are murderers (murderers),

We cant make them get no furtherer,

The SPG them are murderers (murderers),

We cant make them get no furtherer,

Cos they killed Blair Peach the teacher,

Them killed Blair Peach, the dirty bleeders.

Blair Peach was not an English man,

Him come from New Zealand,

Now they kill him and him dead and gone,

But his memory lingers on.

Oh ye people of England,

Great injustices are committed upon this land,

How long will you permit them, to carry on?

Is England becoming a fascist state?

The answer lies at your own gate,

And in the answer lies your fate.

Campaigners are now demanding a fresh inquiry into Blair Peach's death Gareth Peirce, the lawyer who defended many of those arrested in 1979, said: “Unquestionably a public investigation is required as to what happened and why it was covered up for so long. A man was killed, wholly innocent people were convicted and evidence against them fabricated.

“The police went out to deliberately inflict injuries on innocent people and were being provocative and racist. An onslaught of violence was unleashed on the Southall community and other protesters. The Hillsborough inquiry shows that reopening investigations into incidents that happened in the past is not only important but achievable.”

Darcus Howe writer and anti racist activist remarked: “The death of Blair Peach is a lasting injustice. But it is also a pressing issue because there is no evidence that the policing mistakes that led to the death of Blair Peach have been consigned to the past.”

It is sad that battles which were fought against state-sanctioned violence and far-right racism are still the battles being fought today, and we should not forget that Blair Peach wasn’t the first person nor the last to be killed by the police, since his murder Mark Duggan, Ian Tomlinson, Jean Charles de Menezes; are some other people who have had the misfortune of being famous because they were killed by the Metropolitan Police. The fight for justice goes on, as does Blair Peach's legacy who believed in the inclusion of everyone no matter what race, religion or educational ability. We must continue to confront and resist the forces of fascism and racism everywhere.

The death of Blair Peach was the dire outcome of a double-edged state racism. The police that day staunchly protected a racist gathering in a predominantly Asian community, while unleashing militarised measures of control and punishment on demonstrators looking to oppose the fascists (Institute of Race Relations, 1979).http://www.irr.org.uk/

Blair Peach’s death became a focal point for those who questioned the nature of the Special Patrol Group and the general lack of police accountability which that force epitomised. And, from the agitation of Blair’s family, especially his long term partner Celia Stubbs, about the inadequacy of the inquest system and the secrecy surrounding the coroner’s court and the evidence withheld from the family, was created the organisation INQUEST.

The Metropolitan Police commissioned an internal inquiry into what happened, which was led by Commander John Cass. 11 witnesses saw Peach struck by a member of the Special Patrol Group (SPG). The SPG was a centrally-based mobile group of officers focused on combating serious public disorder and crime that local divisions were unable to cope with. It started in 1961, and was replaces in 1987 by the Territorial Support Group, which also has a less-than stellar reputation amongst activists.

The pathologist’s report concluded that Peach was not hit with a standard issue baton, but an unauthorised weapon like a weighted rubber cosh,or a hosepipe filled with lead shot. When Cass’ team investigated the headquarters of the SPG, they found multiple illegal weapons including truncheons, knives, a crowbar, and a whip. 2 SPG officers had altered their appearance by growing or cutting facial hair since the protest, 1 refused to take part in an identity parade, and another was discovered to be a Nazi sympathiser. All of the officers’ uniforms were dry-cleaned before they were presented for examination.

Cass concluded that one of 6 officers had killed Peach, but he couldn’t be sure who exactly, because the officers had colluded to cover up the truth. He recommended that 3 officers be charged with perverting the course of justice, but no action was ever taken. The results of the inquiry were not published, and the coroner at the inquest into Peach’s death refused to allow it to be used as evidence, despite making use of it himself. Two newspapers, the Sunday Times and the Leveller, published leaks naming the officers that had travelled in the van that held Peach’s killer. They were Police Constables Murray, White, Lake, Freestone, Scottow and Richardson. When the lockers of their unit were searched in June 1979, one officer Greville Bint was discovered to have in his lockers Nazi regalia, bayonets and leather covered sticks. Another constable Raymond White attempted to hide a cosh. The failure of the authorities to adeguately invstigate Peach's murder left a huge feeling of resentment. Celia Stubbs, said: "This report totally vindicates what we have always believed - that Blair was killed by one of six officers from Unit 1 of the Special Patrol Group whose names have been in the public domain over all these years."

An annual award has since been presented by the UK's National Education Union to teachers to carry on Blair Peach's memory and after his death a number of writers have dedicated poems to his memory, including Chris Searle, Michael Rosen and Susannah Steele, Louis Johnson, Edward Bond, Sigi Moos, Sean Hutton and Tony Dickens, and songs including the following by dub poet Linton Kwesi Johnson in Jamaican patois.

:

Everywhere you go its the talk of the day,

Everywhere you go you hear people say,

That the Special Patrol them are murderers (murderers),

We cant make them get no furtherer,

The SPG them are murderers (murderers),

We cant make them get no furtherer,

Cos they killed Blair Peach the teacher,

Them killed Blair Peach, the dirty bleeders.

Blair Peach was an ordinary man,

Blair Peach he took a simple stand,

Against the fascists and their wicked plans,

So them beat him till him life was done.

Everywhere you go its the talk of the day,

Everywhere you go you hear people say,

That the Special Patrol them are murderers (murderers),

We cant make them get no furtherer,

The SPG them are murderers (murderers),

We cant make them get no furtherer,

Cos they killed Blair Peach the teacher,

Them killed Blair Peach, the dirty bleeders.

Blair Peach was not an English man,

Him come from New Zealand,

Now they kill him and him dead and gone,

But his memory lingers on.

Oh ye people of England,

Great injustices are committed upon this land,

How long will you permit them, to carry on?

Is England becoming a fascist state?

The answer lies at your own gate,

And in the answer lies your fate.

Campaigners are now demanding a fresh inquiry into Blair Peach's death Gareth Peirce, the lawyer who defended many of those arrested in 1979, said: “Unquestionably a public investigation is required as to what happened and why it was covered up for so long. A man was killed, wholly innocent people were convicted and evidence against them fabricated.

“The police went out to deliberately inflict injuries on innocent people and were being provocative and racist. An onslaught of violence was unleashed on the Southall community and other protesters. The Hillsborough inquiry shows that reopening investigations into incidents that happened in the past is not only important but achievable.”

Darcus Howe writer and anti racist activist remarked: “The death of Blair Peach is a lasting injustice. But it is also a pressing issue because there is no evidence that the policing mistakes that led to the death of Blair Peach have been consigned to the past.”

It is sad that battles which were fought against state-sanctioned violence and far-right racism are still the battles being fought today, and we should not forget that Blair Peach wasn’t the first person nor the last to be killed by the police, since his murder Mark Duggan, Ian Tomlinson, Jean Charles de Menezes; are some other people who have had the misfortune of being famous because they were killed by the Metropolitan Police. The fight for justice goes on, as does Blair Peach's legacy who believed in the inclusion of everyone no matter what race, religion or educational ability. We must continue to confront and resist the forces of fascism and racism everywhere.

No comments:

Post a Comment