Just after the First World War he became acquainted with three other Surrealist poets; Andre Breton, Phillipe Soupault and Louis Aragon, as well as becomming friends with the Surrealist Painter Max Ernst. He was to have a long association with them until around 1938. Experimenting with rythym, automatic writing, dreams and reality, and new verbal techniques soon became an everyday motion, and the poems that he created in this time are considered to be among the best that emerged out of the Surrealist movement.

After losing his first wife Gala, a mysterious and intuitive women to first Max Ernst, then subsequently to Salvador Dali, he spent a long time bereft in losing her love, however in 1934 he remarried Maria Benz ( Nusch) , an actress and model who was friends of Man Ray and Picasso.

After the Spanish Civil War which deeply affected him, he abandoned his Surrealist experimentations and in 1942 joined the Communist Party, and his work from now on reflected his growing militancy, and his rejection of tyranny, dealing with the sufferings and brotherhood of man,and the political and social ideasof the previous century. He began to regard poetry as a means towards radical change.During the Second World War he wrote verse that inspired and raised the morale of members of the French Resistance Movement.

After the war he continued to write on themes of Peace, self government and liberty. He married again to a Dominique Laure in 1951, who he had met at the Congress of Pea, Mexico, 1949. Sadly a year later he died of a heart attack in Paris. His legacy is found in the beauty of his words, his voyage through great moments in history, his life of tumultuous emotion and passionate imagination. His later work manifests the delicacy that was apparent even in his most political poems of the war years.

The following piece was originally given as a lecture at the New Bulington Galleries, 24th June, 1936.

Translated by George Reavey

H Read, Surrealism (Faber, 1936) pp171-176)

' The time has come for poets to proclaim their right and duty to maintain that they are deeply involved in the life of other men, in communal life.

On the high peaks!- yes, I know there have always been a few to try and delude us with that sort of nonsense; but. as they were not there, they have not been able to tell us that it was raining there, that it was dark and bitterly cold, that there one was still aware of man and his misery; that there one was still aware and had to be aware of vile stupidity, and still hear muddy laughter and the words of death. On the high peaks, as elsewhere, more than elsewhere perhaps, for him who sees, for the visionary, misery undoes and remakes incessantly a world, drab, vulgar, unbearable and impossible.

No greatness exists for him that would grow. There is no model for him that seeks what he has never seen. We all belong to the same rank. Let us do away with the others.

Employing contradictions purely as a means to equality, and unwilling to please and be self-satisfied, poetry has always applied itself, in spite of all sorts of persecutions, to refusing to serve other than its own ends, an undesirable fame and the various advantages bestowed upon conformity and prudence.

And what of pure poetry? Poetry's absolute power will purify men, all men. 'Poetry must be made by all. Not by one.' So said Lautreamont. All the ivory towers will be demolished, all speech will be holy, and, having at last come into the reality which is his, man will need only to shut his eyes to see the gates of wonder opening.

Bread is more useful than poetry. But love, in the full, human sense of the word, the passion of love is not more useful than poetry. Since man puts himself at the top of the scale of living things, he cannot deny the value to his feelings, however no-productive they may be. 'Man.' says Feuerbach, 'has the same senses as the animals, but in man sensation is not relative and suborinated to life's lower needs - it is an absolute being, having its own end and its own enjoyment.' This brings us back to necessity. Man has constantly to be aware of his supremacy over nature in order to guard himself against it and conquer it.

In his adolescense man is obsessed by the nostalgia of his childhood; in his maturity, by the nostalgia of his youth, in old age by the bitterness of having lived. The poet's images grow out of something to be forgotten and something to be remembered. Waerily he projects his prophecies into the past. Everything he creates vanishes with the man he was yesterday. Tomorrow holds out the promise of novelty. But there is no today in his present.

Imagination lacks the imitative instinct. It is the spring and torrent which we do no re-ascend. Out of this living sleep daylight is ver born and ever dying it returns there. It is a universe without association, a universe which is not part of a greater universe, a gogless universe, since it never lies, since it never confuses what will be with what has been. It is the truth, the whole truth, the wandering palace of the imagination. Truth is quickly told, unreflectively, plainly; and for it, sadness, rage, gravity and joy are but changes of the wether and seductions of the skies.

Salvador Dalis Portrait De Paul Eluard

The poet is he who inspires more than he who is inspired. Poems always have great white margins, great margins of silence where eager memory consumes itself in order to re-create an ecstacy without a past. Their principal quality is, I nsist again, not to invoke, but to inspire. So many love poems without an immediate object will, one fine day, bring lovers together. One ponders over a poem as one does over a human being. Understanding, like desire, like hatred, is composed of the relatioship between the thing to be understood and the other things, either understood or not understood.

It is hope or his despair which will determine for the watchful dreamer - for the poet - the workings of his imagination. Let him formulate the hope or despair and his relationship with the world will immediately change. For the poet everything is the object of sensations and consequentlly, of sentiments. Everything concrete becomes food for his imagination, and the motives of hope and despair, together with their sensations and sentiments, are resolved into concrete form.

I have called my contribution to this volume 'Poetic Evidence'. For if words are often the medium of the poetry of which I speak, neither can any other form of expression be denied it. Surrealism is a state of mind.

For a long time degraded to the status of scribes, painters used to copy apples and become virtuosos. Their vanity, which is immense, has almost always urged them to settle down in front of a landscape, an object, an image, a text, as in front of a wall, in order to reproduce it. They did not hunger for themselves. But Surrealist painters, who are poets, always think of something else. The unprecedented is familiar to them, premeditation unknown. They are aware that the relationships between things fade as soon as they are established, to give place to other relationships just as fugitive. They know that no description is adequate, that nothing can be reproduced literally. They are all animated by the same striving to liberate the vision, to unite imagination and nature, to consider all possibilities a reality, to prove to us that no dualism exists between the imagination and reality, that everything the human spirit can concieve and create springs from the same vein, is made of the same matter as his flesh and blood, and the world around him. They know that communication is the only link between that which sees and that which is seen, the striving to understand and to relate - and, sometimes, that of determining and creating. To see is to understand, to judge, to deform, to forget or forget oneself, to be or to cease to be.

Those who come here to laugh or to give vent to their indignation, those who, when confronted with Surrealist poesy, either written or painted, talk of snobbism in order to hide their lack of understanding, their fear or their hatred, are like those who tortured Galileo, burned Rousseau's books, defamed William Blake, condemned Baudelaire, Swinburne and Flaubert, declared that Goya or Courbet did not know how to paint, whistled down Wagner and Stravinsky, imprisoned Sade. They claim to be on the side of good sense, wisdom and order, the better to satisfy their ignoble appetites, exploit men, prevent them from liberating themselves - that they may the better degrade and destroy men by means of ignorance, poverty and war.

The genealogical tree painted upon one of the walls of the dining-room of the old house in the north of France, inhabited by the present counts de Sade, has only one blank leaf, that of Donatien Alphonse Franciois de Sade, who was imprisoned in turn by Louis XV, Louis XV1, the Convention and Napoleon. Interned for thirty years, he died in a madhouse, more lucid and pure than any of his contemporaries.

In 1789, he who had indeed deserved the title of the'Divine Marquis' bestowed upon him in mockery, called upon the people from his cell in the Bastille to come to the rescue of the prisoners; in 1793, though devoted body and soul to the revolution, and a member of the Section des Piques, he protested against the death penalty, and reproved the crimes perpetrated without passion: he remained an aethiest when Robespierre introduced the new cult of the Supreme Being; he dared to pit hisgenius against that of the whole people just beginning to feel its new freedom. No sooner out of prison that he sent the First Consul the first copy of a pamphlet attacking him.

Sade wished to give back to civilised man the force of his primtive insticts, he wished to liberate the amorous imagination from its fixations. He believed that in this way, and only in this way, would true equality be born.

Since virtue is its own reward, he strove, in the name of all suffering, to abase and humiliate it; he strove to impose upon it the supreme law of unhappiness, that it might help all those it incites to build a world befitting man's immense stature.Christian morality, which, as we often have to admit to our despair and shame, is not yet done with, is no more than a mockery. All the appetites of the imaginative body revolts against it. How much longer must we clamour, struggle and weep before the figures of love become those of facility and freedom?

Let us now listen to Sade and his profound unhappines: ' To love and to enjoy are two very different things: the proof is that we love daily without enjoyment, and more often still we enjoy without loving.' And he concludes: ' Moments of isolated enjoyment thus have their charms, that they may even possess them to a greater degree than other moments; yes, and ii it were not so many old men, so many dissemblers and people full of blemishes, enjoy themselves? They are sure of not being loved; they are certain that it is impossible to share their experience. But is their pleasure any the less for that?

Chateau de Vincennes de Dade prison

And justifying those me who introduce some singularity imto the things of love, Sade rises up against those who regard love as proper only to the perpetuation of their miserable race... ' Pedants, executioners, turnkeys, legislators, tonsured rabble, what will become of you when we shall have reached that point? What will become of your laws, of your morality, of your religion, of your gallows, of your paradise, of your gods, of your hell, when it shall be demonstrated that such and such a flow of liquids, such a kind of fibre, such a degree of acidity in the blood or in the animal spirits, is sufficient to make a man the object of your penalties or your rewards?'

It is the perfect pessimism which gives his wors their sobering truth. Surrealist poetry, the poetry of always, has never achieved more. These are sombre truths, and almost all the rest is false. And let us not be accused of contradictions when we say this! Let them not try to bring against us our revolutionary materialism! Let them not tell us that man must live first of all by bread! The maddest and the most solitary of the poets we love have perhaps put food in its proper place, but that place is the highest of all because it is both symbolical and total. For everything is re-absorbed in it.

There is no portrait of the Maequis de Sade in existence. It is significant that there is none of Lautreament either. The faces of these two fantastic and revolutionary writers, the most desperately audacious that ever were, are lost in the night of the ages.

They both fought against all artifices, whether vulgar or subtle, against all traps laid for us by that false and importune reality which degrades man. To the formula: You are what you are,' they have added: ' You can be something else.'

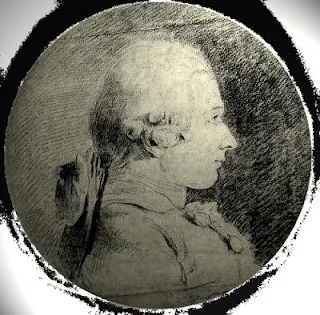

The only known official portrait of the Marquis de Sade

painted by Charles Amadee Phillipe Van Loo

in 1761 when de Sade was 20 or 21

He will then no longer be a stranger either to himself or to others. Surrealism, which is an instrument of knowledge, and therefore an instrument of knowledge, and therefore an instrument of conquest as well as of defence, strives to bring light man's profound consciousness. Surrealism strives to demonstrate that thought is common to all, it strives to reduce the differences existing between men, and, with this end in view, it refuses to serve an absurd order based upon inequality, deceit and cowardice.

Let man discover himself, know himself, and he will at once feel himself capable of mastering all the treasures, material as well as spiritual, which he has accumulated throughout time, at the price of the most terrible sufferings, for the benefit of a small number of privileged persoms who are blind and deaf to everything that constitues human greatness.

Today the solitude of poets is breaking down. They are now men among other men, they have brothers.

There is a word which exalts me, a word I have never heard without a tremor, without feeling a great hope, the greatest of all, that of vanquishing the poer of the ruin and death afflicting men - the word is fraternisation.

In February 1917, the Surrealist painter Max Ernst and I were at the front, hardly a mile away from each other. The German gunner, Max Ernst, was bombarding the trenches where I, a French infantryman, was on the look-out. Three years later, we were the best of friends, and ever since we have fought fiercely side by side for one, and the same cause, that of the total emancipation of man.

Max Ernst- At the Rendezvous of friends , 1922

seated from left to right: Rene Crevel, Max Ernst, Dostolevsky, Theodore Fraenkel, Jean Paulhan, Benjamim Peret, Johannes Baargeld, Robert Desnos.

Standing: Phillipa Soupalt, Jean Arp, Max Morise,

Raphael, Paul Eluard, Louis Aragon, Andre Breton, Giorgio de Chirico, Gala Eluard.

In 1925, at the time of the Moroccan war, Max Ernst upheld with me the warhchword of fraternisation of the French Communist Party. I affirm that he was then attending to a matter which concerned him, just as he had been obliged, in my sector in 1917, to attend to a matter which did not concern him. If only it had been possible for us, during the war, to meet and join hands, violently and spontaneously against our common enemy: THE INTERNATIONAL OF PROFIT.

'O you are my bothers because I have enemies!' said Benjamin Peret.

Even in the extremity of dscouragement and pessimism, we have never been completely alone. In present- day society everything conspires at every step we take to humiliate us, to constrain us, to enchain us and to make us turn back and retreat. But we do not overlook the fact that this is so because we ourselves are the evil, the evil in the sense in which Engels meant it; that is so because, with our fellow men, we are conspiring in our turn to overthrow the bourgeoisie, and its ideal of goodness and beauty.

That goodness and that beauty are in bondage to the ideas of property, famil, religion and country - all of which we repudiate. Poets worthy of the name refuse, like proletarians, to be exploited. True poetry is present in everything that does not conform to the morality which, to uphold its order and prestige, has nothing better to offer us than banks, barracks, prisons, churches, and brothels. True poetry present in everything that liberates man from that terrible ideal which has the face of death. It is present in the work of Sade, or Marx, or of Picasso, as well as in that of Rimbaud, Lautreamont or of Freud. It is present in the invention of the wireless, in the Tcheliouskin exploit, in the revolt of the Asturias, in the strikes of France, and Belgium. It may be present in chill necessity, that of knowing or of eating better, as well as in a predilection for the marvellous. It is over a hundred years since the poets have descended from the peaks upon which they believed themseklves to be established. They have gone out into the streets, they have insulted their masters, they have no gods any longer, they have dared to kiss beauty and love on the mouth, they have learned the songs of revolt sung by the unhappy masses and, without being disheartened, they try to teach them their own.

They pay little heed to sarcasms and laughter, they are accustomed to these; but now they have the certainty of speaking in the name of all men. They are masters of their own coscience.'

Honest Justice

It is the burning law of men

From grapes they make wine

From coal they make fire

From kisses they make men

It is the unkind law of men

To keep themselves whole in spite

Of war and misery

In spite of the dangers of death

It is the gentle law of men

To change water into light

Dreams into reality

Enemies into brothers

A law old and new

A self-perfecting system

From the deopths of the child's heart

Up to the highest judgement

The same day for all

The sword we do not sink in the heart of the guilty's

masters

We sink in the heart of the poor and innocent

The first eyes are of innocence

The second of poverty

We must know how to protect them

I will condemn love only

If I do not kill hate

And those who have inspired me with it

A small bird walks in the vast regions

Where the sun has wings

Her laughter was about me

About me she was naked

She was like a forest

Like a multitude of women

About me

Like an armour against wilderness

Like an armour against injustice

Injustice struck everywhere

Unique star inert star of thick sky which is the privation

of light

Injustice struck the innocent the heroes and the madmen

Who shall one day know how to rule

For I heard them laugh

In their blood in their beauty

In misery and torture

Laugh of a laugh to come

Laughter at life and birth in Laughter.

Liberty

On my schoolboy's notebooks

On my desk and on the trees

On sand on snow

I write your name

On all pages read

On all blank pages

Stone blood paper or asg

I write your name

On gilded images

On the weapons of warriors

On the crowns of kings

I write your name

On jungle and desert

On nests on gorse

On the echoe of my childhood

I write your name

On the wonders of nights

On the white bread of days

On bethrothed seasons

I write your name

On all my rage of azure

On the pool musty sun

On the lake lving moon

I write your name

On fields on the horizon

On the wings of birds

And on the mill of shadows

I write your name

On each puff of dawn

On the sea of ships

On the demented mountain

I write your name

On the foam of clouds

On the sweat of storm

On thick insipid rain

I write your name

On shimmerimng shapes

On bells of color

On physical truth

I write your name

On awakened pathways

On roads spread out

On overflowing squares

i write your name

On the lamp that is lit

On the lamp that butns out

On my reunited houses

I write your name

On the fruits cut on two

Of the mirror and my chamber

On my bed empty chamber

I write your name

Onn my dod greedy and tender

On his trained cars

On his awkward paw

I write your name

On the springboard of my door

On familiar objects

On the flood of blessed fire

I write your name

On all turned flesh

On the foreheads of my friends

On each hand outstretched

I write your name

On the window of surprises

On the attentive lips

Well above silence

I write your name

On my destroyed refugees

On my crumbled beacons

On the walls of my weariness

I write your name

On absence without desire

On naked solitude

On the steps of death

I write your name

On health returned

On the risk dissapeared

On hope without memory

I write your name

And by the power of a word

I start my life again

I was born to know you

To name you

Liberty

The Last night

1

This murderous little world

Is oriented toward the innocent

Takes the bread from his mouth

Gives his house to the flames

Takes his coat and his shoes

Takes his time and his children

This murderous little world

Confounds the dead and living

Whitens the mud pardons traitors

And turns the world to noise

Thanksmidnight twelfe rifles

Restore peace to the innocent

And it is for the multitudes to bury

His bleeding fish his black sky

And it is for the multitudes to understand

The fraility of murderers.

2

The would be a light push against the wall

It would be being able to shake this dust

It would be to be united.

3

They had skinned his hands from bent his back

They had dug a hole in his head

And to die he had to suffer

All his life.

4

Beauty created for the happy

Beauty you run a great risk

These hands crossed on your knees

Are the tools of an assasin

This mouth singing aloud

Serves as a beggar's bowl

And this cup of pure milk

Becomes the breast of a whore.

5

The poor picked their bread from the gutter

Their look covered light

No longer were they afraid at night

So weak their weakness made them smile

In the depths of their shadow they carried their body

They ssaw themselves only through their distress

They used only an intimate language

And I heard them speak gently prudently

Of an old hope as big as a hand

I heard them calculate

The multiplied dimensions of the autumn leaf

The melting of the wave on the breast of a calm sea

I heard them calculate

The multiplied dimension of the future force.

6

I was born behind a hideous facade

I have eaten I have laughed I have dreamed I have been

ashamed

I have lived like a shadow

Yet I knew how to sing the sun

The entire sun which breathes

In every breast and in all eyes

The drop of candour which sparkles after tears.

7

We throw the faggot of shadows to the fire

We break the rusted locks of injustice

Men will come who will no longer fear themselves

For they are sure of all men

For the enemy with a man's face dissapears.

Poems Reprinted from

The Penguin Book of Socialist Verse

Edited by Alan Bold

Penguin, 1970